Meet Seven Indigenous Women Fighting for their Cultures and Territories in the Amazon

Across the Amazon, Indigenous women are fighting to protect their cultures, lands and lives. Today, on International Women’s Day, we celebrate the power of Indigenous women as powerful leaders in building just and sustainable solutions to the twin crises of climate change and biodiversity loss, and we invite you to get to know seven inspiring women defenders from the Kofan, Siona, Siekopai and Waorani nations.

Working closely with our sister organization, the Ceibo Alliance— the first Indigenous-led intertribal alliance of its kind across Ecuador, Peru, and Colombia— these women are working to protect five million acres of rainforest from natural resource extraction and industrial encroachment. In a coordinated effort across their communities, they are advancing female empowerment and leadership, movement building, community organizing, territorial mapping and monitoring initiatives. They are also creating community-led enterprises and women’s associations that focus on income-generating socio-agricultural projects, as well as the recovery of plant medicines and traditional healing systems to offer sustainable economic alternatives for Indigenous women, families and communities.

Alicia Salazar

“As women, we are organizing and uniting to defend our territories so that our children may live in a healthy environment, free from contamination. We are fighting to protect and sustain our territory and biodiversity for future generations. We are deeply connected to our Mother Earth, we are defenders of life.”

- Alicia Salazar, Siona Leader & Director of Ceibo Alliance

Alicia Salazar is a Siona leader and Director of the Ceibo Alliance. Born on the banks of the Putumayo River, on the border between Ecuador and Colombia, in the ancestral territory of the Siona nation. Alicia Salazar emerged as a leader in her people’s resistance to the predation of oil companies. As Director of Ceibo Alliance, Alicia works to develop programs to defend Indigenous territories in the northwestern Amazon and to motivate other women to become protagonists in resistance movements. In 2020, Ceibo Alliance was awarded the prestigious United Nation’s Equator Prize in honor of its integral strategies to protect Indigenous Rights and the Amazon, and for its extraordinary grassroots solutions to climate change.

Nemonte Nenquimo

“We are taking a stand for the planet. Throughout the world, women, not just Indigenous women, must take leadership to build the future. For our children, so that they can live well, healthy, without disease, without pollution.”

- Nemonte Nenquimo, Waorani Leader & Co-Founder of the Ceibo Alliance

Nemonte Nenquimo is at the forefront of the Indigenous movement in the Amazon, widely recognized for her defense of Waorani territory and culture from the threat of resource extraction. She is one of the founding members and visionaries of the indigenous organization Ceibo Alliance. In 2019, Nemonte was elected as the first woman president of the Waorani organization of Pastaza Province. Nemonte led her people in an historic legal victory against the Ecuadorian government, which protected half-a-million acres of primary rainforest in the Amazon and set a precedent for Indigenous rights across the region. Her work has been recognized around the world, and she is the winner of the Goldman Environmental Prize 2020 for Central and South America, United Nations’ Champions of the Earth, BBC 100 Women of 2020 and TIME 100 most influential people in the world.

Leorvis Payaguaje

“We must always protect our territory; it is a legacy for our children. We must fight to maintain our culture. We must not forget who we are and where we come from. Our territory is our life, it is home to much flora and fauna and it is our home.”

- Leorvis Payaguaje, member of the Siekopai nation & Founder of the Siekopai Women’s Association ‘ASOPROASIENW’

Leorvis Payaguaje, born in the Siekopai community of San Pablo along the banks of the mighty Aguarico River, is the President of the Siekopai women’s association “ASOPROASIENW”, which works to support women-led alternative economies through the marketing of a hallmark of Siekopai gastronomy: Nea’pia, a black chili sauce. Her grandfather, grandmother and grandfather-in-law are all Siekopai healers, bearers of an encyclopedia of ancestral knowledge. Leorvis grew up learning from her grandparents about her people’s traditional cultural practices, and at the same time seeing the influence that Western culture was having on her people and culture. This realization motivated Leorvis to work with Ceibo Alliance and other women in Siekopai communities on initiatives to share ancestral knowledge and cultural practices with the younger generation of women and girls— from traditional ceramics to hammock weaving and traditional cuisine.

Gladyz Vargas

“My dream is that we, Indigenous women, continue to build our leadership so that we can be stronger in our fight to protect the forest in alliance with other nations. We are deeply connected to the natural world and with our children.”

- Gladyz Vargas, Kofan activist & artisan

Gladyz Vargas is a Kofan activist, member of the Ceibo Alliance, and founding artisan member of the Kofan women’s association, Suku. Gladyz has a vision for the well being of her people in a healthy territory, where families can earn an income while preserving their culture and resisting incursions by extractive industries. Born in the Kofán community of Dovuno, and now living in the community of Dureno in the northern Ecuadorian Amazon, Gladyz believes that through working with and for women, she can help strengthen culture, language and ancestral knowledge. Gladyz is leading initiatives that bring isolated Kofán communities together to explore economic alternatives to oil, including the design of traditional garments and sewing workshops, the production and marketing of handicrafts through the Kofan women’s association of Suku, traditional forest-garden cultivation, and participation in local and regional fairs. When COVID-19 hit the Amazon, the women of Suku shifted their efforts to produce face masks, filling a critical void in Indigenous access to protective equipment in the region.

Adiela Jineth Mera Paz

“When you walk through Siona territory, you feel exactly what the elders say, that everything is alive. I dream that our young people will defend our territory. And that will be our legacy. We know that we’re cultivating the air, and that air will help another country that might not always have it. So it’s not just for us. It’s for the world.”

- Adiela Mera Paz, Siona Leader & Guardia Member

Adiela Jineth Mera Paz is a Siona land defender from the Putumayo River on the Ecuador-Colombia border. She was born and raised in the community of Buenavista and is its first female Vice-President. Her voice and leadership was fundamental to the decision taken by the community in 2014 to reject economic offers made by the British oil company Amerisur and initiate a fight for the health and survival of their rainforest territory. She has represented the Siona in government negotiations before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and other spaces, speaking out on the complex threats that Indigenous communities living along the border of Colombia and Ecuador face— including oil extraction and staggering violence borne from armed conflict and the narco-trade. Alongside her community leadership role, Adiela has worked with an operator for the High Commission for Peace to remove anti-personnel mines planted by the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and the Colombian military in Siona territory over the past decade. Her courageous work is profiled in this unique video portrait in The New Yorker.

Alexandra Narvaez

“Today, as women, we are on the frontlines – it is no longer only the men. We are taking on this fight for our territory because our territory is our life, it is our body.”

- Alexandra Narvaez, Kofan defender & Member of the Sinangoe community guardia

Alexandra Narvaez is a young Kofan Indigenous rights and land defender from the community of Sinangoe in the Province of Sucumbios in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Her community is located at the headwaters of the Aguarico River, one of Ecuador’s largest and most important rivers. In 2018, Alexandra’s community won a landmark legal battle against gold mining, protecting more than 79,000 acres of mega-biodiverse primary rainforest. During this pandemic, the Sinangoe community has continued to confront illegal mining, poaching and logging threats, and is working to enforce government compliance with their precedent-setting court ruling. With their case selected by Ecuador’s Supreme Court to set national level jurisprudence on Indigenous people’s right to free, prior, and informed consent, the Kofan are set to return to court this year to expand the enforceable recognition of Indigenous rights across the region. Alexandra is an important spokesperson for her community and is also spearheading her community’s eco-tourism initiatives.

Ene Nenquimo (Norma)

“We will defend our land and our lives until the end. We will never give up. With every step we take, we prove our leadership and autonomy as a people.”

- Ene Nenquimo, Waorani activist & Member of the Ceibo Alliance leadership

Ene Nenquimo (Norma) was born in the Waorani community of Toñampare on the banks of the Curaray River. As a child, her mother and grandmother taught her how to live in good health and in harmony with the rainforest. As she grew older she became aware of the changes occurring in her people’s territory with the increasing arrival of evangelical missionaries and oil companies. She witnessed the environmental and cultural devastation caused by oil extraction during visits to other Waorani communities. At 34 years-old, Norma is a respected leader among the Waorani people and part of the Ceibo Alliance’s leadership council. She works to organize her people and support training for women to lead community initiatives and assume greater roles as community leaders. She is also supporting a myriad of strategies to protect her people’s territory and culture, from the building of their own educational system to territorial monitoring and legal strategies seeking government compliance with the Waorani’s historic legal victory against oil drilling in the Amazon.

Support these women in their fight to protect their cultures, lands, lives and the Amazon for us all. Find out more here.

The Siekopai’s Ancestral Remedy to the Pandemic In The Amazon

“Fighting COVID-19 with Ancestral Wisdom in the Amazon”, A film for The New Yorker created by Siekopai filmmakers in collaboration with Amazon Frontlines & Ceibo Alliance, 2020

“Our cultures and forest hold the wisdom to heal our planet.”

This month, the Siekopai’s extraordinary response to COVID-19 is front and center in a short film on the New Yorker, produced in collaboration with Siekopai filmmakers, and team members of Amazon Frontlines and Ceibo Alliance. The 10-minute film chronicles the Siekopai’s journey to Pëkë’ya or Lagartococha, the heartland of their ancestral territory on the Ecuador-Peru border, where they collected plants to create their own effective remedy to the coronavirus, and shared their medicine with other affected Indigenous nations including the Siona of Putumayo. When all else failed, they turned to their knowledge and forest for answers.

In the face of the COVID-19 emergency, government inaction and a near-collapse health system, the Siekopai decided to face the pandemic by drawing from what they know best: their ancestral wisdom, shamanic acumen, and traditional knowledge of medicinal plants. Accomplished herbalists experimented with different combinations of medicinal plants to develop an effective remedy, which helped community members overcome the virus. Rachel Riederer from The New Yorker explains more in her article here.

In the face of government inaction and a firm sense of solidarity, the Siekopai people distribute their medicinal plant brew to Indigenous nations affected by the coronavirus. This photo, taken earlier on during the pandemic in the month of August 2020, shows Siekopai leader Justino Piaguaje sharing a batch with the Siona people of the Putumayo River

“We must come together to protect and defend our survival.”

“Our people have survived many pandemics. For us, this is a time to remember the past, the history of our ancestors, but above all to save our lives in these circumstances, since we have no support from the local or national government. We must come together to protect and defend our survival. And we must do this by passing on ancestral knowledge to Indigenous people, and non-indigenous people alike”, explains Justino Piaguaje, President of the Siekopai Nation, who led his people’s response to COVID-19 and along with the nation’s elders, spearheaded the distribution of the medicinal brew to other Kichwa, Siona, Waorani, and Kofan communities.

The Siekopai’s COVID-19 response is mirrored by the stories of many other Indigenous nations across the Amazon. In times of unparalleled crisis and seemingly insurmountable odds, Indigenous peoples have continued to demonstrate their resilience and the importance of Indigenous knowledge, values, and territories in the Amazon rainforest. While the Siekopai are actively working to recover the sacred heartland of their ancestral territory, Lagartococha, and press the State for measures to protect their rights and territory during this global pandemic, they have also begun working on a variety of post-COVID-19 initiatives such as the development of their own educational system and the re-establishment of farming systems in their communities to regain their food sovereignty.

“During this pandemic, we have found strength in the path and wisdom of our ancestors. We’ve never lost our connection to our roots and knowledge. We continue to resist. Our cultures and forest hold the wisdom to heal our planet. We hope that our short film helps the world to understand this”, said 25-year-old Jimmy Piaguaje, who, along with his distantly related cousin 22-year-old Ribaldo Piaguaje, documented his people’s response to COVID-19 in the New Yorker film. “As young people, we will continue this struggle to recover our roots, so that the future generations do not forget and understand what it means to be truly Siekopai”, affirmed Ribaldo.

Over the past years, Jimmy and Ribaldo have dedicated themselves to using video, photography and social media to document the teachings of their elders and create stories about their peoples’ struggle for survival in the face of multiple threats, including extractivism, cultural loss and now a global pandemic. Working as part of the Indigenous-led non-profit organization Ceibo Alliance and supported by Amazon Frontlines’ Storytelling Program, which provides training and mentorship to a new generation of Indigenous communicators, Jimmy and Ribaldo launched a multi-part video series on their people’s ancestral medicinal plant knowledge in 2019.

Jimmy and Ribaldo are currently working on several new productions, including the forthcoming release of their new short film, “The Industry of Fire”, which documents the intensifying fire seasons in South America. The film will be released in early 2021 – stay tuned for more details soon!

Record Fires This Year Edge the Amazon Rainforest and Our Climate Closer to the Brink

From Siberia to Australia, California to the Amazon, 2020 was another record setting year for climate fueled fires – the result of rampant greenhouse gas emissions and unabated deforestation. Meanwhile, the world over, we are combatting a virus that likely emerged as a result of human encroachment into wild spaces, with vulnerable communities being the hardest hit. To add insult to injury, the oversight vacuum created by lockdown measures has led to increases in deforestation rates across the Amazon. Globally, since the start of the pandemic forest loss alerts are up 77%. The irony is that the poverty caused by broken systems and emergency responses to the virus are fueling an upsurge in the very practice – deforestation – that could generate the next pandemic and disproportionately harm indigenous land defenders, the very people who are safeguarding our future from the climate crisis and repeated pandemics.

Sketch of a Disaster Foretold

In 2019, the fires raging throughout the Amazon made headlines and pulled heartstrings across the world. This year’s fires have been far worse, but they have been eclipsed in the media by a different deforestation-generated disaster – Covid-19.

In 2019, in Brazil alone, nearly 3000 km2 (735,000 acres) of forest was felled and then burned. Add to this the additional 1,500 km2 (395,000 acres) that burned unintentionally and this is an area a little larger than the state of Rhode Island. Bolivia also had a record fire season in 2019. One of the things that was exceptional about the 2019 fire season was the number of intentionally set fires to clear land for pasture and agriculture.

Compare with 2020. Data from Brazil, dating to mid-September, suggests an area nearly four times greater has been impacted, with forest fires touching roughly 19,000 km2 (4.6 million acres) – an area between the sizes of Connecticut and New Jersey. 2020 has been drier than 2019, but still not a severe drought year. What is likely making the difference is a surveillance void in the wake of regional lockdowns to prevent the spread of Sars-CoV-2.

Unique also to 2020 is the extent of burning in the world’s largest wetland – the Pantanal, a 210,000 km2 expanse in the middle of the South American continent between Brazil, Bolivia and Paraguay, which borders the Amazon in southern Brazil. The Pantanal is home to the densest concentration of jaguars anywhere on earth. Twenty-eight percent, a little less than three times the area that has burned in California, has gone up in flames.

An article, entitled ‘Amazon wildfires: Scenes from a foreseeable disaster’ published in the scientific journal Flora concludes that increases in deforestation and climate-induced forest flammability are creating a critical situation that needs to be acted on urgently through innovation, cooperation and communication. Global efforts will prove ineffective if the Amazon’s best conservationists – Indigenous people – are left out of decision-making spaces and if their land rights are not respected and upheld.

Crimson climate, forest flammability

The main driver of these fires in the Amazon is land clearing by settlers to expand cattle and agricultural operations. Proof of this is that early in the season, in July 2020, 84% of fires burned on recently cleared land, as seen from satellite images. Compounding an already volatile situation, Covid-19 measures have led to a “wild, wild west” scenario which has allowed deforestation rates to skyrocket across the Amazon during the pandemic. A study in Colombia found that a stark increase in forest fires beginning in March 2020 corresponded with an increased presence of armed groups and decreased governmental and non-governmental forest monitoring capacity.

Fires in Brazil’s Amazon increased 13% in the first nine months of the year compared with a year ago, as the rainforest region experiences its worst fire season in a decade. This image shows the remains of what was once forest near Novo Progresso in the state of Para in the Brazilian Amazon, September 2020. Photo Marizilda Cruppe/Amazônia Real/Amazon Watch

The climate is increasingly an accomplice in this arson. The dry season in the Amazon has increased by approximately 0.6 days per year since the 1970s, partly due to deforestation and partly due to climate change. That makes A MONTH more of dry season compared to before industrialization. In that month, twigs and leaves accumulate on the ground, known as necromass, as trees shed biomass in an effort to conserve water. Over the course of the extra month, this leaf litter has a chance to get drier and drier, essentially creating a tinder box.

Meanwhile, studies are pointing at a relatively new problem in the Amazon: fragmentation and forest edges. This has been an issue in other parts of the world, but until recently the expanse of Amazonian forest was so large that the relative proportion of forest edge to intact forest was negligible. However, a recent study has shown that the number and the size of large forest plots decreased significantly from 2001 to 2017 in the Brazilian Amazon. This has an impact on fires because forest edges are drier and more vulnerable to damage from run-away fires. Another study found that post-fire annual tree mortality along forest edges was up to 90% in drought years.

“Decisive Action Now.” When the abstract of a scientific article ends this way, instead of the customary “more research is needed,” you know we’re in trouble.

In a dystopian twist, the fires themselves dry out surrounding forest making them more susceptible to fires the following year and also, in a final blow, contribute to the climate crisis which is sapping the forest of its moisture in the first place.

Climate variability, people’s vulnerability

As has been made all too clear through the global Covid-19 pandemic, disasters hit poorer people hardest, and natural disasters impact people reliant on nature, such as indigenous people, most.

Fires damage people’s property, their livelihoods and their health. In California, 10,488 Structures structures have been destroyed in this year’s fires alone. In the Amazon these figures are unknown, but a recent study found that 43% of people interviewed in an area of the Eastern Brazilian Amazon were affected by fires at least once in the past five years.

Many indigenous people throughout the world depend on forests for most of their food and building materials. Yet, in 2020, ninety percent of the Guató tribes’ land in Brazil has been destroyed, obliterating their crops and wild plants, to give just one example. Overall, there was an 87% increase in the number of fires recorded on indigenous lands in Brazil between 2018 and 2019. Fires are even raging into the land of uncontacted tribes, who depend entirely on the rainforest for their survival. Since the 2020 fire season is still upon us, it is too early to tell what the compounded impacts of increasing deforestation trends, the climate crisis and Covid-created monitoring vacuums will be.

Worrisome effects on human health come in the form of worsening air quality in the region as well. A study found that forest fires led to a 58% increase in hazardous air-borne particulate matter in the Apyterewa Indigenous lands, Eastern Brazilian Amazon, in the 2016-2019 period. Another study showed that hospitalizations among children doubled between the 2018 and 2019 fire seasons in a region of northern Brazil.

How do we get ‘Out of the Woods’

The question becomes, what do we do? Once again, scientists are not hedging: “We have never been so capable of identifying the problems haunting the Amazon as we are in 2020. Our challenge now is to act fast on the solutions, before climate change makes it much harder to solve the fire problem in the Amazon.”

Solutions to keeping destructive practices from further destroying the Amazon have to be collective because each person’s fire risk is dependent on what the neighbors do, both at the farm-level and the nation-to-nation level. This requires leadership, international coordination, high-level communication and collaboration.

Unfortunately, it seems that people in positions of power aren’t heeding the message and won’t do so unless the international community holds their feet to the fire, figuratively speaking, of course. In just one example, Bolsonaro-appointed environment minister Ricardo Salles, who was convicted of “administrative dishonesty” for deliberately altering maps in favor of a mining company, is ending environmental policies designed to keep forests standing at an alarming rate.

The recent Biden-Harris’ win in the US Presidential elections could signal a positive turning point for action on climate and the ecological emergency facing the Amazon rainforest. Biden has pledged to recommit the United States to the Paris agreement on climate change, and advocated for international cooperation to halt Amazon destruction. Indigenous peoples, such as Nemonte Nenquimo hope that Biden “will understand that the Amazon is being driven to the brink of collapse […] and have the courage to take a stand for the Earth and not side with the big industries”. Fortunately, scientists are also increasingly banding together to urge for decisive action: no more promises, no more conferences. Feet on the ground.

It is urgent that banks, customers, companies and countries do all in their power to stop feeding this carnage and encourage other viable options for the Amazon and the people who call it home. Once again, the science is clear…support for an indigenous-led, Amazon-wide halt to deforestation has never been so urgent.

Nothing found.

Our Planet Depends On Indigenous Action: A Message from Ceibo Alliance

As the leadership council of Ceibo Alliance, we’re proud and honored to have been awarded the 2020 UN Equator Prize. For us, this prize is a recognition and validation of our years of movement building and frontlines action to protect our way of life and the Amazon rainforest.

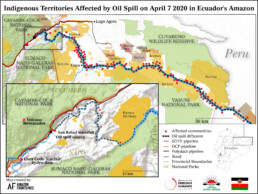

As we write this, our rainforest home is under threat. Fires of unprecedented scale and ferocity rage across the Amazon, set intentionally by cattle ranchers and farmers with the encouragement of governments. Oil companies carve new roads and drill more wells deeper into the forest, while ruptured pipelines spill crude oil into the rivers and streams. A major surge in logging threatens the ancient trees our ancestors walked among. And the COVID-19 virus wreaks havoc among our peoples, carrying off our elders much like the measles, polio and yellow fever of our recent past.

We know what is coming: we are bracing for an extraction boom in the Amazon in light of the global economic recession provoked by the pandemic, as governments double down on non renewable resources in a desperate attempt to boost the economy at the cost of our survival and Earth’s climate. Indigenous Peoples are putting our lives on the line to stop them.

We know what is coming: we are bracing for an extraction boom in the Amazon in light of the global economic recession provoked by the pandemic, as governments double down on non renewable resources in a desperate attempt to boost the economy at the cost of our survival and Earth’s climate. Indigenous Peoples are putting our lives on the line to stop them.

Ceibo Alliance is an organization that brings our communities and our peoples together, and builds the capacity, the networks and the resources that our young leaders need to exercise our rights, defend our lands, govern our territories and keep our people healthy and our cultures alive. Together, we are strengthening community resilience through access to clean water for thousands of families and solar energy for hundreds; leveraging technology to monitor our territories and create maps that tell the real story of our living forest; leading hard hitting legal campaigns to protect hundreds of thousands of acres of rainforest; uplifting women leaders and keeping our cultures alive by holding spaces for knowledge sharing between generations; and using film and digital storytelling to share our voices with the world. As the UN Equator Prize acknowledges and our achievements demonstrate, our movement is real and our model is working.

We are facing a dire moment, as Indigenous peoples and as a planet. As scientists affirm and Indigenous Peoples have been saying for years, the Amazon is at a tipping point. With it, goes any hope of rescuing Earth’s climate. For millennia, and to this day, our people have cared for and defended the forest. We have the greatest stake in its protection, as our physical and cultural survival depends on it, and we have proven to be its most effective guardians.

And yet, of the shockingly small amount of resources that global philanthropy invests in the protection of our planet’s tropical forests, the vast majority is channeled to big conservation organizations and precious little to Indigenous Peoples. Indigenous Peoples are the ancestral owners of more than one quarter of the entire Amazon basin, and roughly 80% of the world’s biodiversity. We believe that resources should go to the people and communities on the frontlines of the battle to protect our planet’s tropical forests– to the Indigenous communities standing up in defense of their lands in the face of some of the mightiest interests on Earth.

In light of major international recognition of the role Indigenous Peoples play in the protection of the world’s most important ecosystems, including the TIME100 honoring Ceibo Alliance co-founder Nemonte Nenquimo and the UN Equator Prize award for Ceibo Alliance, we write this in the hopes that NGOs, the philanthropy sector, and the global public will reflect on what it will really take to set our planet on a sustainable and wise course toward a future in which all of our children and grandchildren will thrive– and invest in the frontlines peoples and movements that can get us there.

5 Razones Por Las Que Una Reciente Victoria En La Corte Constitucional Del Ecuador Alienta La Lucha De Los Pueblos Indígenas Por La Amazonía

La semana pasada la Corte Constitucional del Ecuador, en un veredicto histórico, falló a favor de más de una docena de comunidades indígenas después de una batalla legal de ocho años, cambiando profundamente el panorama de los derechos indígenas, y estableciendo un nuevo precedente importante para muchas luchas en marcha.

Hace ocho años, las comunidades Kichwa y Siona que viven a lo largo de los ríos Putumayo y San Miguel, la frontera natural entre Ecuador y Colombia, descubrió que el Ministerio del Ambiente había declarado unilateralmente sus territorios ancestrales como “Bosque Protector del Triángulo de Cuembí”, y había entregado el control de más de 100.000 hectáreas a las Fuerzas Armadas del Ecuador. Con indignación y determinadas a mantener un control autónomo de sus territorios ancestrales, las comunidades indígenas presentaron una demanda ante la corte ecuatoriana de mayor jerarquía.

La semana pasada, al dictaminar que los actos del Ministerio del Ambiente violaron la Constitución, la Corte marcó un nuevo precedente sobre el derecho de los pueblos indígenas a ser consultados antes de la promulgación de nuevas leyes o regulaciones que los afecten; el derecho a limitar la actividad o presencia militar en sus territorios ancestrales; así como el derecho a poseer un título de propiedad formal sobre los mismos territorios ancestrales.

Los efectos de esta decisión trascienden la cuestión del Bosque Protector del Triángulo de Cuembí, y proveen poderosas herramientas legales para proteger los territorios selváticos indígenas, promover la autonomía indígena, y detener políticas del Gobierno potencialmente dañinas o destructivas. A continuación, viene un desglose de cómo este nuevo fallo de la Corte reforzará las luchas indígenas en el futuro:

1. El Gobierno ecuatoriano no puede aprobar leyes o regulaciones que impacten en los pueblos indígenas sin consultarles primero.

Históricamente excluidos de las decisiones estatales que transformaron y destruyeron su forma de vida y territorios ancestrales, la Constitución Ecuatoriana de 2008 y el derecho internacional otorgan a los pueblos indígenas el derecho a ser consultados antes de que nuevas leyes o regulaciones que puedan impactarlos a ellos o sus territorios sean promulgadas. Se trata del mismo principio detrás del derecho más conocido de los pueblos indígenas a ser consultados antes de que el Gobierno lleve adelante proyectos extractivos o de infraestructura que impacten en sus territorios. Sin embargo, por décadas, el Gobierno ecuatoriano ha sostenido que este derecho a ser consultado se aplica solamente a las leyes aprobadas por la Asamblea Nacional, pero no a los decretos ejecutivos, actos administrativos o regulaciones ministeriales. Innumerables leyes, decretos y regulaciones que han tenido un efecto devastador sobre los pueblos indígenas han sido aprobados sin tan siquiera informarles, mucho menos consultándoles y buscando su consentimiento.

Esto se acabó. Con el veredicto de la semana pasada, la Corte Constitucional dejó completamente claro que los pueblos indígenas deben ser consultados acerca de cualquier ley, decreto, acto administrativo o regulación que los afecte, provenga del Congreso, el Poder Ejecutivo o el Gobierno local. El fallo asegura que los pueblos indígenas pueden expresar su opinión sobre las decisiones del Gobierno a cualquier nivel, desde la entrega de nuevas concesiones petroleras hasta las aprobaciones medioambientales de proyectos de infraestructura, como represas hidroeléctricas, hasta los decretos ministeriales que definan sus derechos adquiridos: los pueblos indígenas deben ser siempre consultados.

2. Docenas de leyes perjudiciales son ahora objeto justo de impugnaciones constitucionales, y el Reglamento sobre procesos de consulta previa para nuevos proyectos mineros, recientemente anunciado por el Ministerio de Energía, se encuentra en un punto muerto.

Mientras el Gobierno ecuatoriano busca redoblar la extracción de recursos naturales y proyectos hidroeléctricos en la Amazonía, este veredicto no solo dará a las comunidades indígenas una poderosa herramienta para prevenir futuras leyes y políticas perjudiciales, sino también para invalidar leyes y políticas que nunca atravesaron el proceso de consulta previa. Dado que el Gobierno ecuatoriano malinterpretó su obligación de consultar a los pueblos indígenas por décadas, como está consagrado, primero, en los tratados internacionales y, luego, explícitamente en la Constitución de 2008, esta es una decisión monumental que pone a docenas de leyes perjudiciales, que van desde regulaciones de petróleo y minería, pasando por titulaciones de tierras indígenas, hasta leyes sobre educación intercultural y salud, en riesgo de ser declaradas inconstitucionales por las cortes.

Es más, el veredicto hace imposible que el Ministerio de Energía y Recursos Naturales No Renovables intente soluciones rápidas de ley, en forma de acuerdos ministeriales, que eludan tanto a los pueblos indígenas como a la Asamblea Nacional, para apurar políticas y regulaciones favorables a las industrias extractivas. Un nuevo Reglamento recientemente anunciado, que pretendía regular el derecho de los pueblos indígenas a la consulta previa sobre proyectos de minería en su territorio, -que los pueblos indígenas y grupos de la sociedad civil incluido Amazon Frontlines estaban preparándose para impugnar- se ha vuelto claramente insostenible. Para el ministro de Energía, René Ortiz, quien recientemente declaró que el Ecuador estaba “sentado sobre Ferraris”, y necesitaba sacar hasta la última gota de petróleo y el último gramo de oro fuera de la tierra, este es un golpe mayor.

“La sentencia es un reconocimiento a la lucha de las comunidades que habitamos en esta zona. Este fallo le dice al gobierno que NO PUEDE tomar decisiones sobre nuestros territorios y nuestras formas de gobernanza sin considerar nuestra voz, que nuestros derechos ancestrales sobre la tierra deben ser garantizados aun cuando no tengamos un pedazo de papel formal que diga que es nuestra, y que tenemos el derecho de mantener nuestros territorios libres de militarización.”

– Alonso Aguinda, presidente de la comunidad de Sionas y Kichwas San José de Wisuya.

3. Los pueblos indígenas tienen derecho a ser propietarios y a gozar de sus territorios, y ya no pueden ser considerados huéspedes en sus propias tierras ancestrales porque ha aparecido una reserva o parque nacional.

La historia de las comunidades Kichwa y Siona descubriendo, sin aviso, que las tierras habitadas por sus mayores y ancestros eran ahora un “parque”, y que ellos eran ahora solo visitantes, no es poco común ni nueva. En los últimos 50 años, el gobierno del Ecuador ha declarado unilateralmente por lo menos 1.4 millones de hectáreas de tierras ancestrales indígenas como parques nacionales o áreas protegidas, concediendo únicamente la propiedad Gobierno, con pocas excepciones. Mientras en ciertas áreas, y bajo ciertos marcos legales, territorios nacionalmente protegidos pueden proveer de un cuidado importante a esos ecosistemas frágiles, en Ecuador, en particular, existe una historia de control pobre sobre invasiones ilegales, explotación maderera y cazadores furtivos, que incluso ha permitido perforaciones petroleras y otras actividades de extracción en parques nacionales debido a lagunas en la ley. Por otra parte, recientes estudios demuestran que el control formal y la titularidad de la propiedad de los pueblos indígenas sobre sus territorios contribuye a la conservación de los bosques y tiene como resultado casi un 10% menos de deforestación que áreas naturales protegidas por fuera de los territorios indígenas.

Lo que la Corte ha dejado claro con esta sentencia es que el interés del gobierno de brindar una mayor protección ambiental a un área, aunque legítimo, no prevalece y no puede infringir el derecho de los pueblos indígenas a ocupar y tener la propiedad formal de sus territorios ancestrales. En este caso en particular, la declaración del Triángulo de Cuembí como Bosque Protector implicaba una prohibición de facto a la titulación de la propiedad de las comunidades indígenas en el área protegida. La Corte afirma que “la relación de los pueblos indígenas con la tierra no es solamente una cuestión de posesión y producción, sino un elemento material y espiritual que debería se plenamente gozado, e incluye preservar su cultura y trasmitirla a las generaciones futuras”. Es más, “la falta de posesión y acceso a sus territorios tiene un impacto [sobre los pueblos indígenas] en el uso y gozo de los recursos naturales que necesitan para sobrevivir, tales como actividades tradicionales de agricultura, caza, pesca, de reunión, entre otras”. La Corte observó que, dado que la decisión del Estado de crear un parque podría afectar, reducir o extinguir los derechos indígenas a la propiedad colectiva de sus territorios, el Estado debía consultar y obtener el consentimiento de esos pueblos indígenas con anterioridad. Este precedente es esencial para que docenas de comunidades indígenas y naciones a lo largo del país puedan finalmente obtener los títulos de propiedad sobre sus tierras.

4. Los pueblos indígenas tienen el derecho a control y gobernar autónomamente sus territorios, y a limitar actividad y presencia militar no deseada.

En este caso en particular, había un evidente motivo ulterior detrás de la declaratoria, por parte del Ejecutivo, del Triángulo de Cuembí como bosque protegido. El río Putumayo es el sustento principal de las comunidades Kichwa y Siona que habitan en sus riberas, pero es también la frontera con Colombia. El Ministerio del Ambiente creó la reserva del Triángulo de Cuembí en 2010, justo en el momento más álgido del conflicto con las FARC y los grupos paramilitares. La región del Putumayo es una de las más activas de Colombia en la producción de hoja de coca, y el río Putumayo y sus afluentes son corredores de narcotráfico clave para los actores armados. Naciones indígenas, como la Siona, han sufrido la peor parte del conflicto armado y la narcoviolencia, pero también han peleado continuamente por el control autónomo de sus territorios, mediante sus propias Guardias indígenas, y afirman que la presencia militar infringe su autonomía y tan solo empeora las cosas.

En un movimiento sin precedentes, el mismo acuerdo ministerial del Ministerio del Ambiente que aprobó la creación del Bosque Protector del Triángulo de Cuembí, también otorgó al Ministerio de Defensa el papel de proteger y controlar el medioambiente y la biodiversidad de la reserva. En esencia, bajo el pretexto del cuidado medioambiental, el Gobierno militarizó las tierras ancestrales de los Kichwa y los Siona. Sobre este punto, la Corte asume un tono más vehemente al amonestar al Ministerio del Ambiente por tomar la absurda decisión de que los militares puedan y deban garantizar la protección medioambiental. Pero más importante, si bien la corte enfatizó la importancia del rol que los militares juegan en la seguridad de las fronteras, también aclaró que los pueblos indígenas tienen el derecho a limitar las actividades militares en sus territorios, y, en este caso, ese derecho fue violado por el acuerdo ministerial que “no fue aprobado por el Congreso y nunca pasó por el proceso de consulta previa o tuvo el consentimiento previo de las comunidades indígenas requerido para este tipo de actividades militares”. El fallo de la Corte reafirma el derecho de los pueblos indígenas a la autonomía y el autogobierno, especialmente para naciones indígenas transfronterizas en zonas de conflictos armados.

5. El fallo se basa en recientes victorias legales de los pueblos indígenas, y provee herramientas para una mayor batalla legal sobre el derecho al consentimiento previo, libre e informado, actualmente, ante la Corte.

Los pueblos indígenas han probado una y otra vez que son los mejores posicionados para pelear por sus derechos, sus territorios ancestrales y nuestro clima global. Con casi el 70% de la Amazonía Ecuatoriana en manos indígenas, el país es un campo de batalla clave para los pueblos indígenas del mundo y la lucha por proteger el bosque tropical más importante del planeta. El derecho a la consulta previa es una herramienta fundamental que las comunidades indígenas están utilizando para proteger sus tierras, bosques y formas de vida, de la embestida de las amenazas extractivas planificadas para sus territorios. A finales de 2018, los A´i Kofán de Sinangoe obtuvieron una victoria judicial que protegió más de 32.000 hectáreas de bosque tropical primario del impacto de la minería de oro, y obligó a las autoridades a tomar medidas de reparación en un área que ya había sido fuertemente impactada por las operaciones mineras. Después, en 2019, el pueblo Waorani ganó una sentencia, suspendiendo indefinidamente la licitación de su territorio a empresas petroleras, protegiendo de inmediato casi 200.000 hectareas de selva tropical, y perjudicando la licitación planificada de 16 bloques petroleros que cubrirían casi 3 millones de hectáreas de territorios indígenas. En ambos casos, la corte dictó que el gobierno había fallado en no consultar de forma adecuada con los pueblos indígenas.

A comienzos del 2020, la Corte Constitucional del Ecuador seleccionó, entre miles de casos, los fallos de los Sinangoe y Waorani para ser revisados, permitiendo la primera oportunidad real del país para una jurisprudencia nacional sobre la aplicación de los derechos indígenas a la consulta previa y la autodeterminación. El resultado determinará si estos derechos constitucionales existen solo en papel o son efectivamente aplicables en la práctica. Esta última sentencia, empero, es un viento poderoso en las velas de los derechos de los pueblos indígenas en Ecuador, así como una señal de aviso al Gobierno de que los pueblos indígenas deben siempre participar en las decisiones que tengan un impacto sobre ellos.

Amazon Frontlines presentó un informe amicus curiae sobre este caso, y proporcionó acompañamiento legal a las comunidades Kichwa y Siona de San José de Wisuya. La organización de derechos humanos ecuatoriana INREDH proporcionó representación legal a las comunidades afectadas. Para saber más sobre nuestro trabajo con las comunidades Kichwa y Siona en el río Putumayo, por favor visita: https://www.amazonfrontlines.org/es/pervivencia-siona/

5 Ways a Recent Ecuadorian Constitutional Court Victory Boosts Indigenous Peoples’ Fight For The Amazon

Last week, in an historic verdict, the Ecuadorian Constitutional Court ruled in favor of more than dozen Indigenous communities after an eight year legal battle, profoundly changing the landscape for indigenous rights and establishing important new precedent for many ongoing struggles.

Eight years ago, Kichwa and Siona Indigenous communities living along the Putumayo and San Miguel River, the natural borderline separating Ecuador and Colombia, found out that the Ministry of the Environment had unilaterally declared their ancestral territories as the “Triangle of Cuembi Forest Reserve” and then gave control of the 100,000 hectare area to the Ecuadorian military. Indignant and determined to keep autonomous control of their ancestral homelands, the Indigenous communities filed a lawsuit with the highest court of Ecuador.

Last week, in ruling that the Ministry of the Environment’s actions violated the Constitution, the Court set new landmark precedent on the Indigenous right to be consulted before enacting new laws or regulations that affect them, not just individual projects, the right to limit the activities or presence of military on their ancestral territories, and the right to possess and hold formal ownership of their ancestral territories.

The effects of this ruling go well beyond the Triangle of Cuembi Forest Reserve, and provide powerful legal tools to protect Indigenous rainforest territories, promote Indigenous autonomy and stop potentially damaging or destructive government policies. Here is a breakdown of how this new Court ruling will bolster Indigenous struggles in the years to come:

1. The Ecuadorian government can’t pass laws or regulations that impact Indigenous peoples without consulting them first.

Historically excluded from decisions by the State that transformed and devastated their way of life and ancestral territories, the 2008 Ecuadorian Constitution and international law give Indigenous peoples the right to be consulted before new laws or regulations that could impact them or their territories are enacted. It’s the same principle behind the more well known right of Indigenous peoples to be consulted before the government can carry out extractive or infrastructure projects that impact Indigenous territories. Yet for decades, the Ecuadorian government has held that this right to consultation only applies to laws enacted in Congress, but not to executive decrees, administrative acts or ministerial regulations. Countless laws, decrees and regulations that have devastating impacts on Indigenous peoples have been passed without so much as informing them, much less seeking consultation and consent. Oftentimes Indigenous communities didn’t know what hit them until years later.

Not anymore. In last week’s verdict, the Constitutional Court made it crystal clear that Indigenous peoples must be consulted on any law, decree, administrative act or regulation that affects them, whether from Congress, the executive branch or local government. The ruling ensures that Indigenous peoples have a say in government decisions at every level, from the granting of new oil concessions to the environmental approvals of infrastructure projects like hydroelectric dams to ministerial decrees that define their rights in practice, Indigenous peoples must always be consulted.

2. Dozens of bad laws are now fair game for constitutional challenges, and the Ministry of Energy’s recently announced draft regulation on prior consultation processes for new mining projects is dead in the water

As the Ecuadorian government looks to double-down on natural resource extraction and hydroelectric projects in the Amazon, this verdict will not only give Indigenous communities a powerful tool to prevent future bad laws and policies, but also to strike down laws and policies that never went through a prior consultation process. Since the Ecuadorian government misinterpreted their obligation to consult Indigenous peoples for decades, as enshrined first in international treaties and then explicitly in the 2008 Constitution, this is a monumental decision that puts dozens of bad laws on subjects ranging from oil and mining regulations, Indigenous land titling, and even laws on intercultural education and health at risk of being declared unconstitutional by the courts.

Moreover, the verdict makes it impossible for the Ministry of Energy and Non-Renewable Resources to sign into law quick fixes in the form of ministerial decrees to sidestep both Indigenous peoples and Congress in order to fastrack favorable policies and regulations for extractive industries. A recently announced draft ministerial decree aimed at regulating Indigenous peoples’ right to prior consultation on mining projects in their territory, which Indigenous peoples and civil society groups including Amazon Frontlines were preparing to challenge, is now made clearly untenable. For Minister of Energy René Ortiz, who recently said that Ecuador was “sitting on Ferraris” and needed to get every drop of oil and every gram of gold out of the ground, this is a major blow.

“This ruling is a recognition of our long fight for justice as communities living along the border. It tells that government that it CANNOT make decisions about our territories and our forms of self-government without considering our voice, that our ancestral land rights must be guaranteed even when we don’t have a formal piece of paper that says it is ours, and that we have the right to keep our territories free of militarization.”

– Alonso Aguinda, President of the Siona and Kichwa community of San José de Wisuya (pictured)

3. Indigenous peoples have the right to own and enjoy their territories, and can no longer be “parked out” of their ancestral lands to make room for a national park or reserve

The story of Kichwa and Siona Indigenous peoples finding out without warning that the rainforest lands inhabited by their elders and ancestors was now a “park”, and that they were now just visitors, is neither uncommon nor new. Over the last 50 years, the government of Ecuador has unilaterally declared at least 1.4 million hectares of ancestral Indigenous lands as national parks or protected areas, granting sole ownership to the government with few exceptions. While in certain areas and under certain legal frameworks nationally protected areas can provide important environmental protections to fragile ecosystems, Ecuador in particular has a poor history of controlling illegal invasions, logging and poachers and even allows for oil drilling and other extractive activities in national parks due to loopholes in the law. Moreover, recent studies show that formal control and ownership by Indigenous peoples of their land advances forest conservation and result in almost 10% less deforestation than protected natural areas outside of Indigenous territories.

What the Court makes clear in this verdict is that the government’s interest in providing increased environmental protection to an area, while legitimate, does not outweigh and cannot infringe upon Indigenous peoples’ right to occupy and have formal ownership of their ancestral territories. In this particular case, the declaration of the Triangle of Cuembi Forest Reserve implied a de facto prohibition on land-titling for Indigenous peoples in the reserve area. The Court notes that Indigenous peoples’ “relationship with the earth is not merely a question of possession and production, but rather a material and spiritual element that should be fully enjoyed, including to preserve their cultural identity and transmit it to future generations.” Moreover, “the lack of possession and access to their territories has an impact on [Indigenous peoples’] use and enjoyment of the natural resources they need to survive, such as traditional activities of agriculture, hunting, fishing and gathering, among others.” The Court observed that since the State’s decision to create the park could affect, reduce or extinguish Indigenous rights to collective property of their territories, the State needed to consult and obtain consent from those Indigenous peoples beforehand. For dozens of Indigenous communities and nations across the country, this precedent is essential to finally getting formal land title over their lands.

4. Indigenous peoples have the right to autonomously control and govern their territories, and limit unwanted military activities and presence

In this particular case, there was a clear ulterior motive behind the Ecuadorian executive branch’s declaration of the Triangle of Cuembi as a nationally protected forest reserve. The Putumayo river is the lifeline of the Kichwa and Siona communities who live along its banks, but it is also the border to Colombia. The Ministry of the Environment created the Triangle of Cuembi reserve in 2010, at the height of the armed conflict with the FARC, guerilla movement,and paramilitary groups. The Putumayo region is one of Colombia’s most active in coca leaf production, and the Putumayo river and its inlets are key narco-trafficking corridors for armed-actors. Indigenous nations like the Siona have borne the brunt of the armed-conflict and narco-violence, but have continuously fought for autonomous control of their territories through their own Indigenous land-patrols, saying that military presence infringes on their autonomy and only makes things worse.

In an unprecedented move, the same Ministry of the Environment decree that approved the Triangle of Cuembi Forest Reserve also granted the Ministry of Defense the role of protecting and controlling the environment and biodiversity of the reserve. In essence, under the pretext of environmental protection, the government militarized the ancestral homelands of the Kichwa and Siona. On this issue, the Court takes a more aggressive tone in admonishing the Ministry of the Environment for taking the absurd position that the military could and should take on the role of environmental protection. But more importantly, while the Court emphasized the important role the military plays in securing the border, it also clarified that Indigenous peoples have the right to limit military activities in their territories, and in this case that right was violated by a ministerial decree that “wasn’t passed by Congress and never went through a process of prior consultation nor had the prior consent of the Indigenous communities required for these types of military activities.” The Court’s ruling affirms Indigenous people’s rights to autonomy and self-governance, especially for trans-border Indigenous nations in conflict-zones.

5. The ruling builds on recent Indigenous legal victories in Ecuador, and provides momentum for a major court battle on the right to free, prior and informed consent currently before the Court.

Indigenous peoples have proven time and again that they are best-positioned to fight for their rights, their rainforest territories and our global climate. With nearly 70% of the Ecuadorian Amazon in Indigenous hands, the country is a key battleground for Indigenous peoples and the broader struggle to protect our planet’s most important rainforest. The right to prior consultation is a fundamental tool that Indigenous communities are exercising to protect their lands, forests and way of life from the onslaught of extractive threats planned for their territories. In late 2018, the A’i Kofán of Sinangoe won a court victory that protected more than 32,000 hectares of primary rainforest from the impacts of gold mining and forces authorities to set in place restoration measures in an area that had been already heavily impacted by the mining operations. Then in 2019 the Waorani won a verdict indefinitely suspending the auctioning of Waorani lands to oil companies, immediately protecting nearly 200,000 hectares of forest land and calling into question the planned auctioning of 16 oil blocks over nearly 3 million hectares of Indigenous territory. In both cases, the court ruled that the government failed to adequately consult Indigenous peoples.

In early 2020, the Constitutional Court of Ecuador selected the Sinangoe and Waorani rulings for review out of thousands of cases, setting up the country’s first real opportunity for national jurisprudence on the application of Indigenous rights to prior consultation and self-determination. The outcome will determine whether these constitutional rights exist only on paper or are actually applicable in practice. This most recent ruling is yet another powerful wind in the sails of Indigenous rights in Ecuador and a warning shot to the government that Indigenous peoples must always participate in the decisions that impact them.

Amazon Frontlines filed an amicus curiae brief in this case and provided legal accompaniment to the Siona and Kichwa community of San José de Wisuya. The Ecuadorian human rights organization INREDH provided legal representation of the impacted communities. To learn more about our work with the Siona and Kichwa communities along the Putumayo River, please visit: https://www.amazonfrontlines.org/sionasurvival/

La Colaboración De Un Cineasta Con Los Siona Para Contar Su Historia En Defensa De La Amazonía

En este artículo, el cineasta estadounidense Tom Laffay, cuyo cortometraje inspirador “Siona: Defensores de la Amazonía Bajo Amenaza” se estrenó recientemente en The New Yorker, nos lleva al interior de su proyecto cinematográfico a largo plazo con el pueblo Siona de Putumayo.

Las amenazas que enfrentan las comunidades indígenas que viven a lo largo de la frontera de Colombia y Ecuador, como los Siona de Putumayo, son únicas y complejas. Además de las industrias extractivas que invaden la mayor parte de la cuenca amazónica, estas comunidades viven en medio de la violencia a raíz del conflicto armado y del narcotráfico. Siendo Colombia el país más peligroso del mundo tanto para los defensores indígenas como para los activistas por los derechos humanos, abogados o cineastas que los apoyan y acompañan, muy pocas historias de la región llegan a una audiencia internacional.

Nosotros, desde Amazon Frontlines, nos hemos inspirado en el pueblo Siona desde el primer día que bajamos de la canoa en las riberas del río Putumayo a su territorio hace muchos años. Esperamos que su historia crítica sirva para inspirar a otros.

“Siona: Defensores de la Amazonía Bajo Amenaza”, una película dirigida por Tom Laffay por The New Yorker y apoyada por The Pulitzer Center, 2020

Texto de Tom Laffay

“El tigre quitó su piel lentamente, enseñando sus entrañas, había una mancha negra dentro de él. Estaba triste” Taita Pablo Maniguaje, un sabio chamán siona, traduce la visión: “Mi pueblo está en peligro”

Como cineasta, se trata tanto de escuchar como de mirar. Si has pasado algún tiempo en la Amazonía probablemente puedes recordar ciertos sonidos con claridad. El trinar de los pájaros, los monos aulladores, las cigarras y las ramas que caen, la lluvia que fluye intermitentemente todo día, el flujo de cantidades incalculables de agua alrededor. En el territorio indígena siona, a lo largo del río Putumayo entre Colombia y Ecuador, escuchas canciones que han sido cantadas por milenios. Cantos que son poderosos, pero delicados, rítmicos y deliberados. Estos son cantados en una ceremonia de Yagé (Ayahuasca), una antigua práctica de búsqueda de visión guiada por los líderes espirituales de los siona o Taitas. Y en la oscuridad, escuchando la lluvia caer del cielo del Putumayo, tu mente divaga y se asienta, como si estuvieras siguiendo al Taita Pablo por un camino de la selva, hasta su realidad, hasta la historia: pasada, presente y futura.

Por miles de años, los siona han cantado a lo largo de la noche para calmar las lluvias, pedir abundante caza, proteger a los guerreros jóvenes y hablar con los muertos. Ahora, estas canciones están siendo quebradas. Otros sonidos perforan la noche. Un intercambio de armas de fuego o el redoble mecánico de una plataforma petrolífera palpitando a través de la selva alteran el espacio sagrado de la ceremonia. Durante un ritual purificador de la mañana, mientras el sol se filtra a través de las hojas y la selva se despierta, la estridente frecuencia magnética de un detector de minas se mezcla incómodamente con el mundo natural. “Las FARC comenzaron a plantar minas antipersonales dentro del resguardo, donde las familias fueron confinadas y desplazadas. Quiero que el resto del mundo comprenda nuestra situación como líderes indígenas, por reclamar, por exigir ya somos señalados, ya somos desaparecidos. Pero si no tenemos el territorio y no lo queremos, no somos zio bain (siona)”, dice Adiela Mera Paz, la joven líder presentada en la película de The New Yorker, ‘Siona: Defensores de la Amazonía Bajo Amenaza’.

La líder Siona, Adiela Mera Paz, graba un área sospechosa de contaminación por minas como parte de su trabajo para la Campaña Colombiana contra las Minas en el territorio de Siona en diciembre de 2019. Una foto de “Siona: Defensores de la Amazonía Bajo Amenaza”, una película dirigida por Tom Laffay por The New Yorker y apoyada por The Pulitzer Center, 2020

Los siona viven en la entrada noroeste de la Amazonía. “Cuando uno anda por el territorio Siona siente exactamente qué dicen los abuelos que todo eso es vida. Todo tiene vida, un árbol, una hoja, hasta la más pequeñita. Nuestros abuelos nos guían y nos enseñan cuál es la importancia; y el deber de nosotros como zio bain es cuidar y proteger el territorio”, dice Adiela. Su verdadero nombre es Zio bain (en su propia lengua mai´cocá) significa “pueblo del Yagé”, la planta medicinal comúnmente conocida por su nombre en kichwa, Ayahuasca, que significa “liana de los espíritus”. El Yagé es la fuerza guía de los siona y se consume religiosamente en las ceremonias por los Taitas o mayores espirituales, para determinar el camino que su pueblo debe seguir. Es un canal –una ventana hacia el mundo de los espíritus y un maestro que los instruye acerca de cómo vivir bien– que permite a sus ancestros ser guiados por “gente invisible” – guardianes espirituales de la selva y el cielo. Como dice Adiela: “Nuestros abuelos nos han indicado que proviene de una planta sagrada que dicen que es un cabello que viene de dios. [El Yagé] es lo más sagrado que tenemos como pueblo siona. Esto es de mucho aprendizaje, para ser guiados y realizar todos nuestros propósitos”.

En 2009, la nación Zio Bain (siona) fue declarada por la Corte Constitucional de Colombia “en riesgo de extinción física y cultural debido al conflicto armado”, desplazamiento y la presencia de minas antipersonales, junto a otras 33 naciones indígenas que habitan en Colombia. Trece años después, los siona atraviesan su mejor momento organizativo desde que su población comenzó a disminuir a mediados de 1900, y están implementando una atrevida estrategia de defensa territorial. Trabajando junto a Amazon Frontlines y otras organizaciones de derechos humanos están sentando un precedente para las otras nacionalidades indígenas, quienes están aprendiendo de los siona de las técnicas de organización e incidencia con la Comisión Interamericana de Derechos Humanos. Mario Erazo Yaguaje, Coordinador Territorial del Resguardo de Buenavista de los siona, aceptando su responsabilidad, dice: “Somos como un ejército espiritual de mucha humildad, que trasciende hacia lo visible”.

A pesar de una negociación en 2016 entre las FARC y el gobierno colombiano, el país no está en paz. En ningún lugar, es esto más visible que, tal vez, en el departamento de Putumayo, donde los siona han vivido por milenios. Confrontaciones armadas a menudo se suceden dentro o alrededor del territorio siona, dejando las casas acribilladas con agujeros de balas de alto calibre, animales sacrificados y, en algunos casos, miembros de la comunidad siona asesinados. Órdenes judiciales, investigaciones de derechos humanos y reportajes periodísticos serios han sido completamente ignorados por las compañías petroleras que operan cerca del territorio siona, lo cual exacerba los riesgos de violencia por parte de actores armados y amenaza seriamente las vías fluviales, la vida silvestre y la cultura de la que los siona dependen y sobre la que construyen su cosmovisión – una comprensión filosófica y espiritual del mundo.

Deberíamos conocer a los siona y otros pueblos indígenas como objetores de conciencia de la guerra que el capitalismo neoliberal está llevando a cabo sobre nuestro planeta.

Dedico mi vida a informar sobre cuestiones que creo son importantes y a ser un puente para las historias de Latinoamérica. He vivido en Colombia por casi cuatro años, reportando sobre la violencia en marcha contra líderes sociales civiles, quienes muchas veces pertenecen a comunidades indígenas, durante el problemático proceso de paz del país. En 2018, poco después de trabajar en Ecuador donde había hecho amistad con un miembro de la comunidad siona, mi mamá murió de cáncer. Mi nueva amiga me invitó a tomar yagé con ella en ese momento difícil. La ceremonia fue mi introducción a la espiritualidad del pueblo siona, y fue donde, por casualidad, conocí a Mitch Anderson, fundador de Amazon Frontlines. Mitch me conectó con el equipo legal de Amazon Frontlines que trabajaba con los siona. A través de esa colaboración recién nacida, pasé 6 meses en conversaciones con líderes siona y expertos legales, aprendiendo los problemas que afronta la nación siona. En agosto de 2019, fui invitado por Taita Pablo a realizar un primer viaje para “tomar medicina y conversar” sobre las ventajas de hacer un documental con los siona de manera que puedan contar su historia al mundo Occidental. Después de recibir la bendición de los mayores de los siona, comenzamos una colaboración para contar su historia de identidad y espiritualidad dentro del contexto presente. Es una historia intergeneracional sobre diferentes personas, cada una bregando con sus propios conflictos interiores, mientras pelean para reafirmarse como pilares de su comunidad y defender la cultura siona. El corto publicado en The New Yorker es solo el precursor de un largometraje que estoy produciendo en colaboración con el pueblo siona.

Los siona son considerados líderes en la defensa de la Amazonía, una reputación que han ganado mediante la feroz defensa de su cultura espiritual, de la que hay señales en cada faceta de sus estrategias de defensa territorial. “Ellos no juegan según el libro, ellos invierten el guión de los oficiales del gobierno y las compañías de petróleo porque los siona y los Taitas operan en otro plano. Es inspirador, es efectivo y da esperanza a cualquiera que esté a su alrededor”, dijo Brian Parker, abogado que trabaja con Amazon Frontlines. Comunicar la importancia de la cultura y la historia de los pueblos indígenas de la Amazonía desde su propia perspectiva ha sido siempre un mensaje clave de los siona. Y como un joven cineasta con el privilegio de colaborar con los siona, tengo la responsabilidad de comunicar su mensaje a la sociedad Occidental de una manera que atraviese los estereotipos y llegue al corazón de las cosas — a la verdad profunda, trascendente. En palabras de Adiela: “Anhelo y sueño, cuando yo ya este ancianita que haya otras jóvenes que digan ‘estamos defendiendo el territorio’ y este es nuestro legado. Porque sabemos que estamos cultivando el aire, ese aire va servir a un país que de pronto entonces solamente no es para nosotros, es para el mundo”.

Los siona son considerados líderes en la defensa de la Amazonía, una reputación que han ganado mediante la feroz defensa de su cultura espiritual, de la que hay señales en cada faceta de sus estrategias de defensa territorial.

En mi casa en Bogotá, en estos tiempos de aislamiento forzado por el Covid-19, no dejo de pensar en los pájaros mochileros que pasan como un enjambre cada tarde volando por la ribera de la comunidad siona de Buenavista, y, en mi ignorancia, no estoy seguro de si están saliendo a cazar o regresando para finalizar el día. De cualquier manera, ellos construyen los nidos más hermosos, que cuelgan con todo su peso en el calor tropical, y protegen a sus residentes en las tardes cuando el viento barre a través del río y se lleva el calor a otro lado. Es entonces cuando nos acomodamos en nuestras hamacas en la casa de Taita Pablo, cuando está oscuro afuera, cuando todo está quieto, cuando el calor se disipa. Él pone una hoja de plátano en el piso, enciende incienso en la escalera de la entrada de la casa, y tampoco estoy seguro si es para dar la bienvenida a alguien o para mantener a alguien afuera. Su canción inicia, en una tonalidad alta al comienzo; me dijo que estaba hablando “con los espíritus de la lluvia esa noche, para limpiar todo en la tierra y preparar una clara noche de visiones para sus discípulos”– unos diez hombres de la Guardia Indígena con los que estábamos bebiendo Yagé. Taita Pablo canta con fuerza, bendiciendo el espacio que ahora es cálido, mientras la energía se arremolina alrededor con los viajes y enseñanzas de todos los hombres reunidos. Me siento recibido con un acogimiento que solo he sentido antes cuando regresaba a casa a la cocina de mi mamá, recibido por mi hermano y hermana con abrazos y la ofrenda y de comida y bebida. Era lo mismo. Me siento en el suelo frente a Taita Pablo. Mario me anima a reconocer lo que el Yagé me ha dado y a agradecer al Taita. Lo hago, y cerramos el pacto de trabajar juntos para contar la historia que los siona quieren contar al mundo. Tengo la esperanza de que el mundo la escuche.

The Pact: A Filmmaker’s Collaboration With The Siona To Tell Their Story In Defense of The Amazon

In this article, American filmmaker Tom Laffay, whose inspiring short film “SIONA: Amazon’s Defender’s Under Threat” recently premiered on The New Yorker, takes us on a journey into his long-term film project with the Siona people of Putumayo.

The threats facing indigenous communities living along the border of Colombia and Ecuador, like the Siona of Putumayo, are unique and complex. On top of the encroaching extractive industries that plague most of the Amazon basin, these communities live amidst staggering violence from both the armed conflict and the narco-trade. With Colombia standing as the world’s most dangerous country for both indigenous human rights defenders and the activists, lawyers or filmmakers who support and accompany them, very few stories from the region reach an international audience.

We at Amazon Frontlines have been inspired by the Siona from the first day we stepped off the canoe on the riverbanks of the Putumayo River into their territory many years ago. We hope that their critical story and history serve to inspire others.

“SIONA: Amazon’s Defender’s Under Threat”, A film directed by Tom Laffay commissioned by The New Yorker and supported by The Pulitzer Center, 2020

Text by Tom Laffay

“The jaguar slowly peeled back his skin to reveal his entrails, where a black stain was within him. He was sad.” Taita Pablo Maniguaje, a Siona elder and healer, translates the vision, “My people are in danger.”

As a filmmaker, it’s as much about listening as it is about seeing. If you’ve spent any time in the Amazon you can probably recall certain sounds with clarity. The whooping birds, the howler monkeys, the cicadas and the falling branches, the flowing rain on and off all day, the surrounding flow of incalculable quantities of water. In Siona indigenous territory along the Putumayo River between Colombia and Ecuador, you hear songs that have been sung for millenia. Chants that are powerful yet delicate, rhythmic and intentional. These songs are sung in Yagé (ayahuasca) ceremony, an ancient vision quest practice led by the Siona’s spiritual leaders, or Taitas. And in the darkness, listening to the rain fall from the Putumayo sky, your mind wanders and settles, as if you’re following Taita Pablo down a jungle path, into his reality, into history— past, present and future.

For thousands of years, the Siona have sung throughout the night to ease the rains, call for plentiful game, protect young warriors and speak with the dead. Now, the songs are being broken. Other sounds pierce the night. An exchange of machine gun fire, or the mechanical drumming of an oil rig pulsing through the jungle, disrupts the sacred space of ceremony. During a morning cleansing ritual, as the sun filters through the leaves and the jungle awakes, the high-pitch, magnetic frequency of a landmine detector mixes uneasily with the natural world. “The FARC started to plant the landmines inside the reservation, where families were confined and displaced. I want the rest of the world to understand our situation as indigenous leaders, when we stand up and make demands, we’re targeted and we’re disappeared. But if we don’t defend our territory and we don’t love it, we aren’t Siona.” says Adiela Mera Paz, the young leader featured in The New Yorker film SIONA: Amazon’s Defender’s Under Threat.

The Siona live at the entrance to the Northwestern Amazon. “When you walk through Siona territory, you feel exactly what the elders say, that everything is alive. [They] teach us about the importance of our duty as Siona, to care for and protect our territory,” said Adiela. Their true name, Zio Bain (in their own language Mai’Cocá) means “people of Yagé”, the plant medicine commonly known by its Kichwa language name Ayahuasca, which means ‘bitter vine.’ Yagé is the guiding force for the Siona and is drunk in ceremony religiously by the Taitas, or spiritual elders, to determine the path forward for their people. It’s a conduit— a window into the world of the spirits and a teacher instructing them on how to live well— allowing their ancestors to be guided by “invisible people”— spirit guardians of the jungle and sky. As Adiela says, “Our grandparents have told us that Yagé comes from a sacred plant. That it’s a hair given by God. It’s the most sacred thing we have as a people. Yagé is about learning, to be guided and achieve our purposes.”

In 2009 the Zio’Bain (Siona) Nation was declared by the Colombian Constitutional Court as being “at risk of physical and cultural extinction due to armed conflict,” displacement and the presence of landmines, along with 33 other indigenous nations living in Colombia. Thirteen years later, the Siona are more organized than they’ve been since their numbers began to decline in the mid 1900’s, and they are implementing a bold strategy for territorial defense. Working alongside Amazon Frontlines, and other human rights organizations, they are setting a precedent for other indigenous nations, who are learning from the Siona’s organizing techniques and engagement with the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. Mario Erazo Yaiguaje, the Territorial Coordinator of the Siona Reservation of Buenavista, embracing his responsibility says, “We’re like a spiritual army, a very humble one, converting the spiritual into the visible.”

Despite a 2016 negotiation between the FARC and the Colombian government, the country is not at peace. Nowhere is this more visible, perhaps, than the department of Putumayo, where the Siona have lived for millenia. Armed confrontations often play out in or around Siona territory, leaving houses riddled with large caliber bullet holes, animals slaughtered and, in some cases, Siona community members killed. Court orders, human rights investigations and serious journalistic reporting on this issue have been completely ignored by oil companies operating near Siona territory, exacerbating risks of violence from armed actors and seriously threatening the waterways, animal life and culture that the Siona depend on and base their cosmovision – a philosophical and spiritual worldview. The fight for the Siona’s survival is urgent. Yet the Siona people have mounted a fierce resistance and shown monumental adaptability in maintaining their spirituality and identity through centuries of forced evangelization, colonization, rubber extraction, slavery, narco wars, petroleum extraction and resurgent armed conflict. If anything, we should learn from the Siona and other indigenous peoples as conscientious objectors to the war that neo liberal capitalism is waging on our planet.

If anything, we should learn from the Siona and other indigenous peoples as conscientious objectors to the war that neo liberal capitalism is waging on our planet.

I dedicate my life to reporting on issues I believe are important and to being a bridge for stories from Latin America. I’ve lived in Colombia for nearly four years now, reporting on the ongoing violence against civil society leaders, who are often from indigenous communities, throughout the country’s troubled peace process. In 2018, shortly after working in Ecuador where I had befriended a Siona community member, I lost my mom to cancer. My new friend invited me to drink Yagé with her at that difficult time. The ceremony was my introduction to the spirituality of the Siona people, and it was where, by chance, I met Mitch Anderson, founder of Amazon Frontlines. Mitch connected me with the Amazon Frontlines legal team, which worked with the Siona. Through that nascent collaboration, I spent some 6 months in conversations with Siona leaders and legal experts learning about the issues confronting the Siona Nation. In August 2019, I was invited by Taita Pablo to make an initial trip to “drink medicine and converse” about the merits of making a documentary film with the Siona so they could tell their story to the Western world. After receiving the blessing of the Siona elders, we began a collaboration to tell their story of identity and spirituality within the present context. It’s an intergenerational story about different people, each contending with their own inner conflicts, whilst struggling to stand as pillars of their community and uphold Siona culture. The short film that was commissioned by The New Yorker is just the precursor to a full-length feature film I’m producing in collaboration with the Siona.