Nacionalidad Siekopai desaloja a invasores de su territorio ancestral en la Amazonía ecuatoriana

“Mira esas huellas de botas frescas … no son de uno de nosotros”, dice un miembro de la patrulla terrestre Siekopai, señalando las pisadas que se cruzan en su camino. Él, junto con otros nueve patrulleros terrestres, han estado caminando durante dos días, sumergiéndose profundamente en su tierra ancestral para detectar y monitorear invasiones. Y cuanto más avanzan, más señales encuentran de la presencia de un visitante no deseado: cazadores furtivos.

Siguiendo las huellas frescas, Hurlem Payaguaje, el coordinador de la patrulla terrestre Siekopai de la comunidad de San Pablo, y miembro de la Alianza Ceibo, encuentra una persiana de caza de reciente construcción. La plataforma improvisada, simple pero eficiente, y estratégicamente ubicada, permite al cazador esperar entre los árboles durante la noche hasta que grandes mamíferos, como el venado y la guanta (paca común), vengan a comer frutos caídos. “Alguien estuvo aquí anoche, pero no mató nada. Al menos no esta vez”. Los hombres están nerviosos, pero decididos.

La selva tropical, que ha sido el hogar de la nacionalidad Siekopai de Ecuador durante miles de años, es tan hermosa y compleja como puede ser la Amazonía: árboles gigantes, lianas y epífitas, insectos y pájaros ruidosos, arroyos llenos de vida. Sin embargo, durante las décadas pasadas, el vasto territorio Siekopai se ha visto reducido a sólo una isla de selva a lo largo del río Aguarico, rodeada por monocultivos de palma, campos petroleros y ranchos ganaderos.

En los últimos meses, los Siekopai de San Pablo han aumentado el monitoreo de actividades ilegales dentro de su territorio ancestral, utilizando herramientas tecnológicas como GPS, drones, cámaras fotográficas y cámaras trampa. Con el apoyo de Amazon Frontlines y la Alianza Ceibo, ellos han estado recopilando datos para brindar a las autoridades y a la sociedad civil, evidencias irrefutables de todos los daños causados a su territorio ancestrale, así como de las violaciones sistemáticas de sus derechos al territorio y a la autodeterminación.

El uso de cámaras trampa ha permitido a los Siekopai y a otras nacionalidades, reunir pruebas claras de caza furtiva y otras actividades ilegales dentro de sus territorios. En este video, cazadores furtivos equipados con escopetas, y acompañados de perros de caza, cargan un puma y un venado muertos.

Cuando la colonización traspasa territorios ancestrales

La nacionalidad Siekopai, con una población de menos de 750 personas, ha enfrentado oleadas de invasiones en las últimas décadas, al igual que otros pueblos indígenas cercanos de la Amazonía ecuatoriana. Desde madereros hasta cazadores furtivos, pescadores y asentamientos ilegales, las amenazas se han multiplicado desde que las industrias del petróleo y el aceite de palma construyeron su extensa red de vías e infraestructura, invadiendo los territorios indígenas.

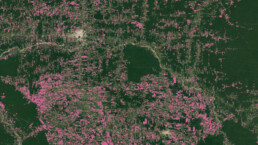

El aumento de la caza furtiva que los siekopai están presenciando dentro de su tierra es solo una de las muchas consecuencias del avance de la colonización hacia áreas remotas y prístinas de la selva. A medida que la frontera colonizadora se expande, también lo hace el acceso por carretera, lo que a su vez aumenta la deforestación y la extracción de recursos. En toda la Amazonía ecuatoriana, las tasas de deforestación aumentaron drásticamente durante la pandemia, lo que convirtió a 2020 en el segundo peor año de pérdida de cobertura forestal de las últimas dos décadas, dejando más de 436.000 hectáreas de bosques vírgenes talados en los últimos 20 años.

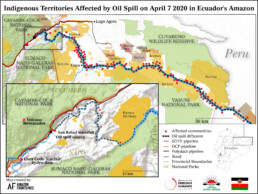

Cronología de imágenes procesadas por satélite que muestran la pérdida de cobertura forestal a lo largo del área del río Kokaya, dentro del territorio ancestral Siekopai, en la cuenca del río Napo, Amazonía ecuatoriana -2001 a 2021-, las cuales muestran cómo los invasores ilegales llegaron a establecerse alrededor de los años 2012 - 2013.

Entre las formas más agresivas de invasión se encuentra el asentamiento de invasores ilegales dentro de los territorios indígenas. En el caso de la nacionalidad Siekopai, esto comenzó hace unos 15 años cuando un grupo de invasores ilegales llegaron a las cabeceras del río Kokaya, un afluente del río Napo. Una década más tarde, estos invasores ilegales habían despejado más de 70 hectáreas de selva virgen para la cría de ganado, principalmente, y degradado otras 100 hectáreas mediante la tala selectiva, la caza furtiva y la destrucción de montes y arbustos que forman el sotobosque.

A pesar de los intentos de los Siekopai por reubicar a los invasores fuera de su territorio, los inquilinos ilegales hicieron más fuerte su dominio sobre la tierra. Pero en 2015 y 2018, los Siekopai finalmente llevaron a los invasores ilegales a los tribunales distritales y provinciales. Los Siekopai ganaron ambos casos, y los tribunales ordenaron a los invasores ilegales que abandonaran estas tierras ancestrales. Desafortunadamente ellos se negaron a cumplir, y las autoridades ecuatorianas tampoco hicieron cumplir los veredictos. El año pasado, otras catorce hectáreas de bosque virgen fueron taladas ilegalmente con total impunidad.

Recuperación de territorios ancestrales mediante el desalojo de invasores ilegales

De vuelta en el campo, mientras las patrullas terrestres de los Siekopai cruzan el río Kokaya hacia el área de invasión, uno sólo puede sorprenderse al ver lo drástico del cambio. Durante las próximas seis horas, la patrulla utilizará alertas de deforestación por satélite para guiar sus pasos y documentar los recientes claros abiertos por los invasores.

Con sus GPS y dispositivos móviles de mapeo en mano, georeferencian casas y tierras de cultivo que se encuentran dentro de los límites de su territorio, mientras vuelan un dron para documentar la magnitud del daño causado por quince años de agricultura. Desde el aire, este pequeño rincón de la Amazonía se parece más a una sabana africana.

Parcelas de deforestación en el área de Kokaya en junio de 2021. Estas se han multiplicado en los últimos años, transformando el territorio ancestral Siekopai en ranchos ganaderos y de monocultivos.

Un día histórico para los Siekopai, una inspiración para otras nacionalidades?

Ante la inacción del Gobierno, los líderes Siekopai decidieron tomar acción por sus propias manos: el 5 de julio de 2021, entregaron un aviso de desalojo de 48 horas a los invasores ilegales. Al cumplirse este plazo, más de 300 personas Siekopai de seis comunidades se reunieron en el área del río Kokaya, con lanzas en mano y vestidas con sus tradicionales túnicas multicolores, en una demostración de fuerza y determinación.

Ancianos, jóvenes, hombres y mujeres, realizaron acciones pacíficas para recuperar el control de su territorio ancestral y ordenaron a los invasores evacuar de inmediato las 15 casas que habían sido construidas ilegalmente allí. En ese día histórico para la nación, los Siekopai lograron recuperar 190 hectáreas de sus territorios ancestrales, y días después del evento, ya estaban encabezando un esfuerzo de reforestación con más de 6.000 árboles pequeños que ayudarán a su tierra a recuperarse de más de una década de cría de ganado.

Jóvenes y ancianos de siekopai, mujeres y hombres unidos para reclamar las territorios ancestrales de su pueblo de manos de invasores ilegales

“No queremos ningún conflicto con nuestros vecinos, ni buscamos represalias por el daño causado a nuestra tierra. Solo pedimos que se respete nuestro territorio y nuestros derechos para que podamos vivir en paz.”– Elias Piaguaje, Presidente de la nacionalidad siekopai de Ecuador

Amparados en la Constitución ecuatoriana (art. 57), dos fallos judiciales y el derecho internacional, sin mencionar un archivo cada vez más robusto de datos de campo recopilados por patrulleros terrestres comunitarios, los Siekopai cuentan con todas las herramientas legales necesarias para recuperar lo que les fue robado. Ellos, sin embargo, continúan enfrentando una batalla cuesta arriba, ya que las autoridades han mostrado un total desprecio por la aplicación de la ley. Además, los invasores ilegales han demostrado su obstinación al negarse a respetar los derechos territoriales de los pueblos indígenas. A pesar de todos los obstáculos, la unidad y la fuerza que demostraron los Siekopai el 7 de julio 2021, podría desencadenar en una ola de acciones similares tomadas por otras naciones vecinas que luchan contra injusticias similares. Para Hurlem Payaguaje y otros miembros de la patrulla terrestre, este es un nuevo comienzo para los pueblos indígenas del norte de la Amazonía ecuatoriana.

Si bien la Constitución ecuatoriana, el derecho internacional y dos casos judiciales les dan pleno reconocimiento de sus derechos sobre el territorio, los Siekopai aún tienen una larga batalla por delante para proteger lo que es más preciado para ellos.

En colaboración con la Alianza Ceibo, Amazon Frontlines acompaña, apoya y capacita a patrulleros y guardias comunitarios de las nacionalidades Siekopai, Siona, A’i Cofán y Waorani para fortalecer sus procesos de defensa territorial. ¡Estén atentos para más historias desde el territorio!

Indigenous Nation in Ecuador's Amazon evicts illegal settlers from its ancestral land

“Look at those fresh boot tracks… these are not from one of us,” says a member of the Siekopai land patrol, pointing to tracks that cross their path. Along with nine other land patrols, they have been walking for two days, venturing deep into their ancestral land to detect and monitor invasions. The further they go, the more signs they see of an unwelcome visitor: poachers.

Following the fresh tracks, Hurlem Payaguaje, the coordinator of the Siekopai land patrol from the community of San Pablo and member of Ceibo Alliance, locates a recently built hunting blind. The makeshift platform, simple but efficient and strategically located, allows the hunter to wait up in the trees overnight for large mammals like brocket deer and lowland paca to come and eat fallen fruits. “Someone was here last night but didn’t kill anything. At least not this time.” The men are nervous but determined.

The rainforest that has been home to the Siekopai Nation of Ecuador for thousands of years is as beautiful and complex as the Amazon can be: giant trees, lianas and epiphytes, noisy insects and birds, and creeks teaming with life. But over the past century, the Siekopai’s once vast territory has been reduced to an island of jungle along the Aguarico River, surrounded by palm monocultures, oil fields and cattle ranches.

Over the past months, the Siekopai of San Pablo have increased their monitoring of illegal activities inside their land using technology such as GPS, drones, photographic cameras, and camera traps. With the support of Amazon Frontlines and Ceibo Alliance, the Siekopai are gathering data to provide authorities and civil society irrefutable evidence of the damages caused to their ancestral lands and the systematic violations of their rights to territory and self-determination.

The use of camera traps has allowed the Siekopai and other nations to gather clear evidence of poaching and other illegal activities inside their land. In this video, poachers equipped with shotguns and accompanied by hunting dogs carry a dead puma and a deer.

When colonization breaches ancestral lands

The Siekopai Nation, with a population under 750 people, has faced wave upon wave of invasion over the past decades, much like other neighbouring Indigenous peoples of the Ecuadorian Amazon. From loggers to poachers, fishermen and illegal settlers, threats have multiplied since the petroleum and palm oil industries built their extended network of roads and infrastructure encroaching on Indigenous territories. The increased poaching that the Siekopai are witnessing inside their land is just one of the many consequences of advancing colonization towards remote and pristine areas of the forest. As the frontier expands, so does road access, which in turn increases deforestation and resource extraction. Across the Ecuadorian Amazon, deforestation rates increased sharply during the pandemic, making 2020 the second worst year for forest cover loss in the past two decades, with a total over 436 000 hectares of pristine forest cleared in the past twenty years.

Timeline of satellite processed images of forest cover loss spreading across the Kokaya River area inside Siekopai ancestral land, Napo River watershed, Ecuadorian Amazon, from 2001 to 2021, showing how illegal settlers moved in around 2012-2013.

Amongst the most aggressive forms of land invasion is the establishment of illegal settlers inside Indigenous territories. In the case of the Siekopai Nation, it started about fifteen years ago when a handful of illegal settlers invaded the headwaters of the Kokaya River, a tributary of the Napo River. A decade later, the illegal settlers had cleared over seventy hectares of pristine rainforest mostly for cattle ranching, and degraded another hundred hectares through selective logging, poaching and understory clearings.

Despite the Siekopai’s attempts to relocate the settlers outside their territory, the illegal tenants tightened their grasp on the land. In 2015 and 2018, the Siekopai finally brought the illegal settlers to court at the district and provincial levels. In both instances, the Siekopai won their cases, and the courts ordered the illegal settlers to leave the ancestral lands. Unfortunately, the illegal settlers refused to comply and Ecuadorian authorities failed to enforce the verdicts. Last year, another fourteen hectares of pristine forest were cleared illegally in total impunity.

Reclaiming ancestral lands by evicting illegal settlers

Back in the field, as the Siekopai land patrols cross the Kokaya river into the invasion area, one can only be shocked to see how drastic of a change there is. For the next six hours, the land patrol uses satellite deforestation alerts to guide their steps and document the recent clearings opened up by the settlers. With their GPS and mobile mapping devices in hand, they georeference houses and farmlands that are located inside the boundaries of their territory, while flying a drone to document the scale of the damage caused by fifteen years of farming. From the air, this small corner of the Amazon looks more like the plains of Nebraska.

Deforestation plots like this one observed in the Kokaya area in June 2021 have multiplied over the past years, transforming ancestral Siekopai rainforests into cattle ranches and farmland.

A historic day for the Siekopai, an inspiration for other nations

In the face of government inaction, Siekopai leaders decided to take matters into their own hands: on July 5th 2021, they handed over a forty-eight-hour eviction notice to the illegal settlers. Forty-eight hours later, over three hundred Siekopai people from six communities gathered in the Kokaya area, spears in hand and dressed in their traditional multicolored tunics, in a demonstration of strength and determination. Elders, youth, men and women took peaceful actions to regain control of their ancestral land and ordered the settlers to immediately evacuate the fifteen houses that had been built illegally on their territory. On that historic day for the nation, the Siekopai succeeded in recovering one hundred and ninety hectares of ancestral Siekopai land. Days after the event, the Siekopai were already spearheading a reforestation effort with over 6000 small trees to help their land heal from over a decade of cattle ranching.

Siekopai youth and elders, women and men united to reclaim their people’s ancestral lands from the hands of illegal settlers

“We don’t want any conflict with our neighbors nor do we seek retaliation for the damage done to our land. We only ask that our territory and our rights be respected so that we can live in peace.”- Elias Piaguaje, President of the Siekopai Nation of Ecuador

With the support of the Ecuadorian Constitution (art. 57), two court rulings and international law, not to mention an increasingly robust archive of field data collected by community land patrols, the Siekopai have all the legal tools needed to reclaim what was stolen from them. However, they continue to face an uphill battle as authorities have shown a total disregard for applying the law. Moreover, the illegal settlers have demonstrated their obstinance in refusing to respect Indigenous land rights. Despite all the obstacles, the unity and strength that the Siekopai demonstrated on July 7th could trigger a wave of similar actions taken by other neighboring nations who struggle with similar injustices. For Hurlem Payaguaje and other land patrol members, this is a new beginning for Indigenous peoples of the northern Ecuadorian Amazon.

While the Ecuadorian constitution, international law and two court cases gives them full recognition of their right over their land, the Siekopai still have a long battle ahead in order to protect what is most precious to them.

In partnership with Ceibo Alliance, Amazon Frontlines accompanies, supports and trains community land patrols of the Siekopai, Siona, Kofan and Waorani nations in order to strengthen their territorial defense processes. Stay tuned for more stories from the ground!

The Real Price of Oil in the Amazon: When Will Negligence and Impunity Stop?

On the 7th of April 2020, the Ecuadorian Amazon experienced its worst oil spill of the past decade. The rupture of two major pipelines and a subsidiary pipeline spilled at least 15,800 barrels of crude oil, polluting pristine ecosystems in one of our planet’s most biodiverse regions, and aggravating an already vulnerable situation for over 120,000 people living downstream from the Coca and Napo rivers. This event was foreseeable and preventable and has triggered dozens of communities and Human Rights organizations to launch a lawsuit against the oil companies and authorities in charge. This blog details how the spill is part of a larger pattern of negligence, impunity and disrespect for indigenous people’s rights and health.

Indigenous People in Ecuador's Amazon File a Lawsuit in the Wake of Catastrophic Oil Spill. Video created by Amazon Frontlines in collaboration with the Alliance of Human Rights in Ecuador, and indigenous organizations CONFENIAE and FCUNAE

Risky beyond measure

The area is jaw-droppingly beautiful, mountains and jungle criss-crossed by rivers and waterfalls, home to one of the highest concentrations of wildlife on the planet and an important source of water for the biggest watershed on Earth. This is the entryway to the Amazon basin, at the foothills of the Ecuadorian Andes, where rivers rush down the steep slopes of volcanoes, finding their way to the flat plains of the flooded rainforest below. Ironically, the path carved by these rivers rushing to the Amazon is the same one that oil industries have built their tracks upon in order to extract oil from the rainforest and transport it through the Andes to the Pacific Coast some 500 kilometers away, using two pipelines: the 50 year-old Trans-Ecuadorian Oil Pipeline System (known by its Spanish acronym SOTE) and the more recent heavy crude pipeline (operated by the private company OCP, owned by oil giants such as Repsol, Occidental and others). A third smaller pipeline, the Poliducto Shushufindi-Quito, uses the same route to transport gasoline, diesel, liquefied petroleum gas and jet fuel from the Amazon to Quito, the country’s capital.

The gateway to the Amazon, at the foothill of the Andes, is one of the most biodiverse places on Earth, but also a highly unstable area where landslides, volcanic eruptions and earthquakes happen regularly

Building pipelines over the Andes is a high risk venture. In one area along the Coca River, a packed assortment of peaks, steep canyons and valleys have been forged by an epic combination of natural processes that remain volatile. Like a ticking time bomb, these characteristics create the perfect conditions for highly unstable soils and large landslides; which threaten any infrastructure built in the area:

- High volcanic activity: The Reventador volcano, with its main active crater located less than 10 kilometers from the pipelines, has been active periodically, including before the construction of the SOTE pipeline in 1960, during its construction in 1972 (1972-1974) and after (1976, 2002 to the present day). Overall, the pipeline runs close to six risk-prone volcanos;

- High seismic activity: According to environmental impact assessment studies conducted for the OCP, the two main pipelines cross 94 seismic fault lines. In 1987, the area was the epicenter of two major earthquakes that caused large landslides and the rupture of the SOTE along 40 kilometers. Scientists had predicted a 66% probability of a major earthquake occurring in this area for the period 1989-1999;

- Frequent flash floods: Abundant and sporadic rainfall (up to 6000 mm/year), coupled with the shape of the Coca River watershed and steep slopes, often produce flash floods in the area.

Despite risks and warnings from environmental impact assessments, these highly unstable conditions were disregarded as the Ecuadorian government’s desire to export oil from the Amazon to the world’s thirsty markets ultimately won out. A first pipeline, the SOTE, was built in 1972, and despite dozens of major spills since its construction, another pipeline, the OCP, was inaugurated in 2003 using supposedly “cutting-edge technology” but following, nonetheless, the same highly unstable route along the Coca River. Promises were made that no spills would occur, but conditions along the Coca River would change drastically.

How one disaster leads to another

In 2016, the Presidents of Ecuador and China jointly inaugurated the Coca Codo Sinclair hydroelectric dam on the Coca River, right on the foothills of the Reventador Volcano and about 12 kilometers from its active crater. The multi-billion dollar project financed and built by China was supposed to “christen Ecuador’s vast ambitions, solve its energy needs and help lift the small South American country out of poverty,” as the New York Times put it. However, not only did the hydro project never reach full capacity due to over 7600 cracks in its structure, it appears that the dam also triggered an aggressive phenomenon known as headward erosion that led to major changes in the course of the river. This type of erosion is a process by which a river erodes its source region, lengthening its channel in a direction opposite to that of its flow.

By cutting the flow of the river, hydro dams built on rivers with a lot of sediment lead to a drastic drop in sediment load, as was the case for the Coca River. Once the newly low-sediment waters pass the dam, their propensity to cause erosion greatly increases in a well known phenomenon called “hungry waters”. This is what many experts think caused the biggest and most famous waterfall in Ecuador to abruptly disappear on February 2, 2020. Located about 15 kilometers downstream from the Coca-Codo dam, the San Rafael waterfall indeed vanished, but the erosion provoked by the hydro dam didn’t stop there. The hungry waters kept eating away at the river bank until the erosion reached, on April 7, 2020, the site where the three pipelines were buried.

Not only was extreme erosion predicted by experts, but satellite imagery captured a month before the oil spill shows that the collapse of the river banks had already moved 800 meters upriver towards the site where the pipelines crossed the river. The Ecuadorian government and the private company that owned one of the pipelines had plenty of time to prevent the spill and avoid such a disaster, but they did nothing despite multiple warnings and publicly stated commitments to put security measures in place.

Such disasters have happened too many times to be simple accidents. Whether it was negligence or intentional, this disaster was caused by serious omissions of state and private obligations, of which Ecuador has a long track record.

The real price of oil in the Amazon

For the past 50 years, Ecuador has been drilling its jungles for oil in a desperate attempt to boost its economy and repay its crushing international debt. Over the past 15 years, the Ecuadorian government has registered over 4000 new oil wells in 68% of the Amazon, or an average of five new wells drilled every week.

On average, five oil wells have been drilled every week over the past 15 years in the Ecuadorian Amazon

With so many oil wells, platforms and pipelines crisscrossing the Amazon, one would think that Ecuador is an oil superpower, when, in fact, the country’s annual oil production barely supplies the equivalent of two days of global oil consumption, out of which over 46% is exported to the US. However, despite such a small amount of extracted oil, the consequences on the environment and local indigenous communities have been disastrous.

From 2010 to 2019, public and private companies extracted over 1,92 billions barrels of oil from the Ecuadorian Amazon, the equivalent of 21 days of global oil consumption.

Ecuador has a terrible track record of oil spills due to the damaging practices first employed by Chevron (previously known as Texaco) and then by others in the Amazon. There were an estimated 714 million barrels of oil and toxic waste water dumped into the environment from 1971 to 1993. There have also been multiple pipeline ruptures throughout this era. According to national Ecuadorian news sources, the SOTE pipeline ruptured 47 times from its inauguration date in 1972 to 2003, when the OCP pipeline was installed.

Other than the OCP and SOTE, hundreds of smaller pipelines also crisscross the far-reaching corners of the jungle. According to Ecuador’s Environment Ministry, more than 1169 oil spills were officially reported from 2005 to 2015 in Ecuador, out of which 81% (952) occurred in the Amazon region. No compiled data has been made public by the government since, so many spills have never been publicly reported.

The end of impunity

For decades, indigenous communities have been the direct victims of the reckless extraction of the oil sector, whose disregard for the environment and failure to take responsibility for its negligence has created a monumental calamity. From the first well drilled in the 1970’s to the latest spill in April 2020, the industry has shown countless times that the Amazon, our world’s most important rainforest, is not an environment fit for oil drilling and pipelines. Unfortunately, the consequences of such irresponsible exploitation is not expressed in dollars, action shares or electoral votes. On the contrary, the impacts are measured by cancer rates, biodiversity loss, toxic loads in fish and medicinal plants, the destruction and contamination of indigenous rainforest homelands, the loss of ancient cultures, traditions and wisdom, and so much more.

A month after the spill, the pipelines have now been rebuilt and the oil flow re-established, even as global oil prices crashed to historic lows and producers around the world scrambled to deal with an enormous excess of oil. Furthermore, the voices of countless indigenous communities have not been heard; the damages to the ecosystem have not been accounted for; and, the contamination of the vital Amazonian food chain has not been addressed. This is why Amazon Frontlines, along with other Human Rights organizations, is supporting communities with a lawsuit against the Ecuadorian government and the oil companies responsible for this latest spill. It is not going to be an easy battle, but the time has come to put a stop to impunity, and for companies and governments to invest in prevention and pay for past damages. Together, we must look towards a post-extractive future.

Help us hold Ecuador and the oil companies accountable by amplifying indigenous communities’ call for #JusticefortheAmazon.

From Big Oil to Palm Oil: Transforming the Ecuadorian Amazon into Monocultures

For decades, the Ecuadorian Amazon has been the epicenter of one of the most polluting oil operations of all times. The oil boom initiated by Texaco in the 1970s is well known as the main driver of deforestation in this strikingly biodiverse forest, home to many indigenous nations. Once the roads have been built for pipelines, oil wells and oil pits, wave after wave of colonists come to clear the forest and establish pastures and agriculture. This drastic conversion has resulted in the loss of over 1 million acres of pristine rainforest since 1990.

However, over the past two decades, one “colonist” has been increasingly expanding in the Ecuadorian Amazon, and without much attention from the public: the African palm oil industry. Radically transforming extremely rich ecosystem into monocultures over large tracts of land, the palm oil industry now occupies over 160 000 acres in the Amazonian provinces of Sucumbíos and Orellana alone, and continues to encroach further and further into indigenous ancestral lands.

A risky, radical land change

Palm oil plantations have more than doubled in Latin America since 2001, and Ecuador is now amongst the top 10 producing countries in the world. One needs to fly over Amazonian palm plantations in order to fully grasp the impact of such large operations. In the province of Sucumbíos, in the Northern Ecuadorian Amazon, blocks of forest covering more than 30 000 football pitches have been converted into palm monocultures.

In this area of the Amazon, two main players control the market: Palmar del Rio, and Palmeras del Ecuador – a subsidiary of Danec S.A. These Ecuadorian companies own over 50% of all palm plantations in the region and buy in bulk from the vast majority of the smaller producers. Interestingly, despite its constant growth, palm oil production in the Amazon is not very profitable, and thus depends on massive subsidies and large-scale operations in order to be successful.

Over 160 000 acres of the Ecuadorian Amazonian rainforest have now been converted into African Palm plantations

One of the main challenges for the palm oil producers is the need for large amounts of fertilizers and pesticides in order to improve their crop yield, to compensate for the nutrient loss resulting from deforestation, and to control insect and fungus infestations. Companies also have to invest massively in the development of new hybrid trees that can resist infestations. These three necessities – pesticides, fertilizers and research and development – require the investment of millions of dollars each year. According to data (2013) from the Ecuadorian government, a palm plantation owner spends on average seven times more money on fertilization and insect and disease control (702$/hectare) than on the actual harvest (100$/hectare) in the first year of harvest.

The fact is, replacing one of the richest and most complex forests in the world with a single-plant system involves high risks for insect and fungus outbreaks, a reality which the Ecuadorian company Palmar del Rio, like many others, learned the hard way. Back in 1998, after clearing nearly 25 000 acres of Amazonian rainforest for its plantation near the town of Coca, this agribusiness lost every single palm tree due to a bud rot infestation, a widespread disease which has affected, and still threatens, hundreds of thousands of acres of palm plantations in Latin America.

Living downstream

The Shushufindi River, surrounded by the biggest African Palm plantations in the Ecuadorian Amazon, is also the main source of fish for the indigenous Secoya community of Bella Vista. Concerned by the chemicals used by the palm oil industry, the community is working with Amazon Frontlines and their indigenous partners of the Ceibo Alliance to measure the amounts of pesticides found in common fish eaten on a daily basis.

Despite these high risks, the loss of primary forests to palm oil production is increasing in the Amazon, and the consequences go far beyond deforestation, biodiversity loss and carbon emissions. Almost all Amazonian palm plantations in Ecuador are located upstream from ancestral Secoya and Siona lands. Streams and rivers crossing entire plantations and accumulating herbicides, insecticides, fungicides and fertilizers also pass through communities, contaminating essential drinking and bathing water, as well as the fish they eat and the soils they use. When you depend upon the forest and river for survival, a 50 000-acre palm plantation is not a good neighbour to have.

Facing these threats to their health and safety, many Siona and Secoya communities have decided to work with Amazon Frontlines and the Ceibo Alliance to monitor contamination levels in the fish they catch. In mid-2018, our teams initiated a pilot project measuring pesticides, heavy metals and hydrocarbon levels in small local fish and secondary catchments from the Shushufindi River. Through our monitoring program, we hope to empower communities by allowing them to gain vital information about the changes and threats to their surroundings, and gather robust evidence which they can use in order to advocate for their rights for greater territorial protection.

Stopping a gold rush in the Amazon: 7 reasons why the Kofan landmark victory is so huge

Facing the mounting pressures of the global race for gold and other metals across the globe, it’s not everyday that a small indigenous community wins a lawsuit against the government that nullifies over 50 mining concessions threatening their health and land, and grants full restoration of the damages done. Last week’s landmark victory for the Kofan people of Sinangoe, at the headwaters of the Aguarico River in the Ecuadorian Amazon, is testament to the importance of indigenous-led resistance against extractivism in the world’s largest tropical rainforest.

This community’s path to victory involved a myriad of strategies ranging from environmental monitoring to innovative legal actions and alliance-building with civil society, provincial governments and international organizations. Its example should provide inspiration and tools to other indigenous peoples facing similar threats to their ancestral lands, cultures and rights. Here are 7 major reasons why Sinangoe’s case is so important.

1. It safeguards the ancestral Kofan way of life

Kofan culture is deeply connected to the land: their entire way of life depends upon the rivers and forest. When the Kofan discovered that their ancestral territory along the Cofanes and upper Aguarico rivers had been granted to mining companies without their permission, they immediately recognized the gravity of this threat to their way of life and autonomy, and to other communities downriver. Damage to these rivers means damage to the Kofan themselves. Their triumphant legal battle, which brought four Ecuadorian State authorities to court, not only denounced the lack of consultation, but also highlighted the violation of their rights to water, food security and a clean environment – fundamental rights imperative to the integrity and survival of Kofan culture.

The Kofan people of Sinangoe have won a landmark legal battle to protect the headwaters of the Aguarico River, strengthening collective rights to Free, Prior and Informed Consent over any extractive activity in indigenous lands.

2. It shows the effectiveness of indigenous-led environmental monitoring

It was Sinangoe’s community land patrol that sounded the alarm when they witnessed the first machines digging up the banks of the Aguarico River in early 2018. This land patrol, trained and formed one year before in partnership with Amazon Frontlines and our indigenous partners Ceibo Alliance, immediately documented and reported the invasion. Over the course of several field trips, the land patrol meticulously built up an extensive archive of images, drone footage and maps, which played a central role in their landmark victory, providing irrefutable evidence of the environmental damages of gold mining on their land to the judges and court. This victory should embolden any community using environmental monitoring techniques, whether it be camera traps, GPS, video recorders, drone, satellite imagery and/or land patrols.

Over the course of 2 years, Sinangoe’s land patrol have used a wide range of strategies and technologies to detect, document and stop gold mining inside and around their ancestral land.

3. It sets a legal precedent for indigenous rights in Ecuador and beyond

The decision by the Provincial Court is without precedent in Ecuador, and takes huge steps towards the protection of indigenous and environmental rights. First, there is the concrete: 20 concessions improperly granted to mining companies canceled; 32 concessions under review for approval indefinitely suspended; and full remediation of damages already caused by the mining activity. But this sentence has deeper repercussions for a country with 14 indigenous nations and some of the world’s most important natural resources. The court’s recognition that the government must consult indigenous communities when the proposed activity affects their territory, even if it doesn’t occur directly on their legally recognized land, is a huge win for indigenous rights to Free, Prior and Informed Consent. Equally important is the recognition of the rights of nature, as well as the use of the precautionary principle, always applicable but seldom-applied in Ecuador, which vests the government with the responsibility to protect the public from harm (in this case to the environment and to the right to water and food security) BEFORE irreversible damage occurs unless scientific evidence can prove otherwise. The court’s decision advances the law in Ecuador, paving the way for other communities to exercise their rights and protect their territories.

4. It protects one of the most biodiverse places on Earth from rampant deforestation

By halting all mining operations along the headwaters of one of Ecuador’s most important rivers, the Kofan have saved 32,000 hectares (79 000 acres) of the most biodiverse rainforest in the country and amongst the most biologically rich places on Earth. The area, fed by the Cofanes and Chingual Rivers, is home to over 3,725 species of plants, 650 species of birds and 50 species of mammals, including various endemic and endangered species like the spectacled bear and the mountain tapir. This biological hotspot’s fragility and uniqueness mean even limited road building and small-scale deforestation could have disastrous impacts on the local flora and fauna. This legal victory affords respite for these wild places and highlights the incompatibility of mining in this pristine Amazon rainforest.

5. It contributes to the fight against the global climate crisis

As deforestation continues to spread across the Amazon, and with the Ecuadorian Amazon having already lost 675,000 hectares of pristine rainforest since 1990, protecting intact refuges like Sinangoe’s ancestral land and its rich surroundings is key to combating climate change. Each hectare of forest in this area contains between 245 to 633 tons of carbon stored in its vegetation and soils, amongst the highest carbon densities in the Amazon1. Avoiding deforestation over 32,000 hectares of this rainforest means avoiding the release of at least 7.8 million tons of carbon to the atmosphere, or the equivalent average yearly carbon emissions of more than 1.7 million cars2.

Deforestation along the banks of the Aguarico River detected by Sinangoe’s land patrol in April 2018.

6. It avoids hazardous contamination of one of the biggest rivers in Ecuador

The Ecuadorian government granting of 52 mining concessions posed a significant threat to the Aguarico river, which crosses the entire Ecuadorian Amazon, providing water to dozens of indigenous communities and to some of the largest cities of the area. Gold mining operations in the Amazon are amongst the main causes of contamination from anthropogenic mercury, a highly toxic heavy metal contaminating water sources and causing serious health impacts for all beings. Moreover, Ecuador allows the use of cyanide for gold extraction, another toxin released into rivers that can pose a serious risk to water quality and health due to its high toxicity. Following Sinangoe’s urgent request during the lawsuit, the Aguarico, Cofanes and Chingual rivers were declared protected water resources by Ecuador’s national water authority (SENAGUA), blocking any mining and any future concessions directly on the banks of these vital rivers, a first in Ecuador.

The Kofan people of Sinangoe have succeeded in building strong ties with allies both nationally and internationally, helping them gain leverage in this fight against the Ecuadorian government.

7. It demonstrates that forging cross-cultural alliances is critical to success

This legal battle would never have been possible if the people of Sinangoe didn’t value their territory, put in long, hard hours patrolling their land, and sustain unity within the community. But that alone wouldn’t have won the battle. What Sinangoe also knew to do was connect with other communities and organizations and reach out for support where needed. Over the course of Sinangoe’s battle against gold mining, over 59 national and international organizations, 14 riparian communities of the Aguarico, the provincial and municipal governments and even the highly influential Catholic Church gave their support to the community, increasing Sinangoe’s leverage and visibility. This example shows that communities in resistance are stronger when they are united, and that cross-cultural alliances work when they are based on mutual respect and trust.

1 Bertzky, M., Ravilious, C., Araujo Navas, A.L., Kapos, V., Carrión, D., Chíu, M., Dickson, B. (2011) Carbono, biodiversidad y servicios ecosistémicos: Explorando los beneficios múltiples. Ecuador. UNEPWCMC, Cambridge, Reino Unido. http://www.unredd.net/index.php?option=com_docman&task=doc_download&gid=6148&Itemid=53

2 EPA. Greenhouse Gas Emissions from a Typical Passenger Vehicle. https://www.epa.gov/greenvehicles/greenhouse-gas-emissions-typical-passenger-vehicle

List of chronicles in our series on Sinangoe:

An unprecedented legal victory for indigenous rights in Ecuador frees up huge swath of Amazonian rainforest from gold mining

On October 22nd 2018, the Kofan people of Sinangoe in the Ecuadorian Amazon won a landmark legal battle to protect the headwaters of the Aguarico River, one of Ecuador’s largest and most important rivers, and nullify 52 mining concessions that had been granted by the government in violation of the Kofan’s right to consent, freeing up more than 32, 000 hectares of primary rainforest from the devastating environmental and cultural impact of gold mining. This precedent-setting decision will inspire indigenous nations across the Amazon and land defenders worldwide for years to come.

The Kofan people of Sinangoe, with the support of Amazon Frontlines and the Ceibo Alliance, have been successful in forcing the Ecuadorian government to cancel all mining concessions on and around their ancestral land, a groundbreaking victory for indigenous rights in Ecuador.

In a historic ruling, the Provincial Court accepted evidence of environmental impacts provided by the community of Sinangoe and the provincial ombudsman, charged the government with not having consulted the Kofan, denounced the mining operations for having violated indigenous rights to water, food and a healthy environment, and cancelled all mining activity in more than 52 concessions at the foothills of the Andes. The ruling, which cites the precautionary principle and uses Ecuador’s new law on the rights of nature, also forces authorities to set in place restoration measures in an area that had been already heavily impacted by the mining operations.

“This is a great victory for our community, for our people and for all indigenous peoples. We are not just fighting for our people, but for everyone who depends on clean water and clean air. This victory is a huge step forward for our children and for future generations. We will remain vigilant in our territory and will continue fighting until we have legal title over our entire ancestral homeland.”

– Mario Criollo, President of the community of Sinangoe.

After only 4 months of mining operations, the environmental damages we have witnessed and documented for the court case provided a strong set of evidence on how granting mining concessions in such a fragile and rich environment is totally incompatible with the Kofan way of life and the conservation efforts needed in this biodiversity hotspot. The area now freed from mining activity is one of the most biodiverse areas on Earth. It is home not only to the Kofan people who depend on its fresh water for survival, but also to more than 3,725 species of plants, 650 species of birds and 50 species of mammals.

Mining operations threaten profound and irreversible environmental and cultural damage in this ecological hotspot as well as the health of the people of Sinangoe and thousands of people in dozens of indigenous communities downstream. Further exposing this highly diverse primary forest to uncontrolled deforestation would also accelerate the global climate crisis.

The headwaters of the Aguarico River, at the core of the Kofan ancestral land and one of the main artery of the Ecuadorian Amazon, were threatened by mercury and cyanide pollution commonly used in gold mining operations in the Amazon, until the Kofan successfully blocked it by suing the Ecuadorian government.

After months of ongoing land patrols, the use of camera traps, drones and satellite imagery, as well as indigenous-driven media campaigns to raise awareness of destructive mining practices, the Kofan people, with the support from Amazon Frontlines and our indigenous partners from the Ceibo Alliance, have succeeded in demonstrating the importance of indigenous-led environmental monitoring and sustained innovative legal strategies to protect their land and rights. Sinangoe now has the important task of ensuring the ruling is respected and the measures dictated by the Courts are enforced on the ground.

“This is a major win for indigenous rights in Ecuador, and a huge wake up call to the Ecuadorian government. Before viewing the land for the minerals underneath it, the Courts now forces authorities to obtain consent from the indigenous peoples who call it home, and to properly evaluate the environmental and cultural costs of allocating such biodiverse hotspots to gold miners.”

– Maria Espinosa, Amazon Frontlines’ legal coordinator and Sinangoe’s lawyer.

List of chronicles in our series on Sinangoe:

Deforestation in the Ecuadorian Amazon: 50 years of oil-driven ancestral land invasion

When I started doing research on deforestation in the Ecuadorian Amazon back in 2001, it was almost impossible to get a clear idea of where and how large the deforestation frontlines in this corner of the Amazon were. The information was scarce, not easily accessible, and often not credible.

However, some alarming clues were already out there. One was from the scientific community, which, back in 1993, had identified the Napo River Watershed, in the heart of the Ecuadorian Amazon, as one of the most active deforestation fronts in the tropical world (namely the Napo Deforestation Front). A bit later, in the mid 2000’s, scientists warned that Ecuador had the highest deforestation rate in South America. At that time, even with the limited information available, it was clear that this mega bio-diverse rainforest was under great pressure.

The oil industry has been the main driver of deforestation in the Ecuadorian Amazon for decades. Roads and pipelines to access oil installations, like this one built by the Chinese Oil giant Andes Petroleum close to ancestral Siona lands, are the typical first blow to rainforest integrity with colonization following suit.

But it was only by traveling throughout the region, and actually crossing the frontlines of deforestation, that I finally witnessed what was really going on: aggressive intrusions into pristine indigenous lands were being mostly driven by the expansion of the oil industry since the 1970’s, through the construction of roads, pipelines, wells, pools, seismic lines, camps and heliports, which, once constructed, led to a second wave of deforestation through rapid colonization and the establishment of pastures.

That was more than 17 years ago.

Once a road is built in the Amazon, both climate and biodiversity are profoundly impacted due to the very nature of this carbon-rich megadiverse ecosystem.

Witnessing a cultural and biological catastrophe in real time

Since then, the expansion of the industrial footprint hasn’t stopped – on the contrary, it has grown (although Ecuador is not the worst of all Amazonian countries). For example, the Ecuadorian Amazon is now crisscrossed by more than 9500 km of roads – or 1.5 times the Earth’s radius – built for pipelines, in order to connect more than 3430 oil wells and to provide access to new pristine areas. New studies also show that the patterns of deforestation in the Amazon are shifting from large blocks to widespread small patches, increasing threats both to climate and biodiversity.

But one positive development is that technologies, satellite images and scientific research have given us a much better understanding of the scale and the impacts of such rapid forest degradation. Now, with just a few mouse clicks, you can see years of satellite data revealing the blows of deforestation. With so much information readily at hand, it has become impossible for industries and the Ecuadorian government to hide their environmental record.

The interactive map from Global Forest Watch shows over 14 years of deforestation in the Ecuadorian Amazon, a very useful free online tool for anyone interested in looking into these issues.

In its 2014 publication on deforestation-driven greenhouse gas emissions submitted to the United Nations, Ecuador declared having lost more than 475,000 hectares of primary Amazon rainforests from 1990 to 2008 Four months later, the country had to readjust its statistics because it had apparently underestimated early 2000-2008 Amazonian deforestation by 25,000 hectares, for a total of 499,000 hectares lost in the Amazon since 1990. If we add up deforestation measured by satellite from 2008 to 2016, the Ecuadorian Amazon has lost 650,000 hectares of pristine rainforest. This represents a massive encroachment on ancestral lands of many indigenous communities at an average pace of 110 American football pitches of forest cleared every day from 1990 to 2016.

Unfortunately, with 68% of the Ecuadorian Amazon divided into oil blocks, Ecuador is planning to push the frontiers even further in 2018 and the years to come, opening up new oil blocks for seismic testing and drilling in the southern Ecuadorian Amazon inside Waorani, Sapara, Achuar and Shuar lands, amongst others. With oil operations already inside iconic protected areas like the Yasuni National Park and the Cuyabeno Wildlife Reserve, it seems like the Ecuadorian government is on a reckless crusade to extract the last drops of crude oil out of the Amazon.

Defending land rights leads to forest protection

Remarkably, despite these waves of deforestation and colonization, pockets of forest are still standing. Research shows that the presence and recognition of ancestral indigenous peoples and territories is amongst the greatest obstacles to deforestation, forest degradation and climate change. Deforestation in the indigenous lands of the Amazon is known to be 2 to 3 times lower than outside recognized ancestral lands.

Amongst the many indigenous peoples of the Ecuadorian Amazon whose ancestral lands are under siege from rampant deforestation and the expanding oil industry, the A’I Kofan community of Dureno is a living testimony of the central role indigenous peoples can play to block deforestation.

When overlaying primary forest cover with boundaries of indigenous ancestral lands in the Ecuadorian Amazon, one can see how indigenous communities are shielding the forests. The case of Dureno, a 10,000 hectare Ai’Kofan territory with an estimated diversity of more than 2,000 plant and 400 bird species, is quite striking. Surrounded on all sides by roads and pipelines, the community has defended its land and avoided the spread of roads into its forest, leaving an island of untouched forest amidst an ocean of oil wells, pipelines and pastures.

Despite constant encroachment on their ancestral lands, indigenous people of the Ecuadorian Amazon, like the A’I Kofan of Dureno, are still standing strong to defend the last of their pristine forests and block deforestation (source: Global Forest Watch).

Working in direct partnership with indigenous communities is at the core of our mission, and while pressures on land, forests and culture are constantly expanding, so are the abilities of indigenous people to take leadership, build networks and shape the resistance. The battle to stop deforestation in the Amazon is the battle to defend indigenous rights to their ancestral lands and cultures. And in return, these forests are amongst our best shields against catastrophic climate disruption, so this fight is of concern for all of us on a global scale. Will you fight with us?

Support our work to protect the Amazon and halt the expansion of extractive industries into ancestral indigenous territories by donating here.

List of chronicles about Deforestation:

Be a Champion for the Amazon!

Start a fundraising campaign to drive resources to Indigenous Earth Defenders on the frontlines

The Kofan people ramp up the fight to protect one of the most biodiverse forests in the Amazon

In January 2018 the Ecuadorian Government concessioned off over 30,000 hectares of some of the most bio-diverse rainforest in the Amazon to an array of mining interests, precipitating a gold-mining boom in the ancestral lands of the Kofan people. There were no prior meetings. No consultation. No information provided to the Kofan villagers of Sinangoe. No permission was asked. The arrival of big machinery, water pumps and dozens of miners was the only courtesy the government gave the ancestral guardians of this biodiversity hotspot.

After months of ongoing land patrols, the use of camera traps, drones and satellite imagery, as well as innovative legal strategies and indigenous-driven media campaigns to raise awareness about destructive mining practices, the Kofan people are on the verge of winning a landmark legal battle to protect the headwaters of the Aguarico River and contribute to the national movement to strengthen collective rights to Free, Prior and Informed Consent over any extractive activity in indigenous lands.

Over 30 000 hectares of mining concessions were granted by the Ecuadorian government in the headwaters of the Aguarico River, Ecuadorian Amazon, without any Free, prior and informed consent from the Kofan community of Sinangoe.

The Kofan peoples’ ancestral rainforest homeland is a miracle of biodiversity – a headwater region where Amazonian forest ascends steep mountainous cliffs into the Andean foothills, home to more species per hectare than anywhere else in Ecuador. The Kofan people, recently featured in a Foreign Policy story about the advantages of indigenous land stewardship, are achieving international recognition for their conservation efforts – which combine cutting-edge tech, weekly land patrols, and tenacious legal advocacy.

Yesterday, the Kofan people’s efforts received an additional boost with a strongly worded letter to Ecuador’s president, Lenin Moreno, signed by 55 national and international organizations, including Greenpeace, Hivos, Amazon Watch and Rainforest Fund. The support comes after the community won a first legal battle in court against four Ecuadorian ministries back in July 2018. In this ruling, a regional judge recognized that Sinangoe’s right to free, prior and informed consent had been violated, and suspended all mining operations in the Aguarico headwaters.

“The presence of mining in the headwaters of the Aguarico River represents a threat to the health of the people of Sinangoe and thousands of people who live downstream, exposes this highly diverse primary forest to uncontrolled deforestation and accelerates the global climate crisis.” – Letter to Lenin Moreno, President of Ecuador

The decision in the lower courts was immediately appealed by all the authorities, and then by Sinangoe and their ally in the Defensoria del Pueblo, who seek an even tougher verdict recognizing that rights to health, water and a clean environment had also been violated and also that the concessions be revoked, not just suspended. The case will be brought in front of provincial judges tomorrow, September 5th 2018, where hundreds plan to gather at the Court of Appeals in the amazonian town of Lago Agrio, coming in support of the Kofan Nation and in defense of the Aguarico River, its pristine headwaters and the vital water it provides to thousands of amazonian people. Stay tuned for more on Sinangoe’s struggle.

List of chronicles in our series on Sinangoe:

Historic indigenous legal victory against gold mining in the Amazon

In a lawsuit that will inspire and galvanize many other indigenous communities across the Amazon for years to come, the Kofan of Sinangoe have won a trial against four Ecuadorian ministries and agencies for having granted or attempted to grant more than 30,000 hectares of mining concessions in pristine Amazonian rainforest on the border of their ancestral land without their free, prior and informed consent. The destructive mining operations that were taking place within these concessions threatened not only the Kofan’s lives, culture and health, but also those of the countless communities located downriver.

In a historic decision on Friday July 27th 2018, a regional judge accepted the evidence provided by the community, charged the government with not having consulted the Kofan, and suspended all mining activity in more than 52 concessions in the headwaters of the Aguarico River. The decision was immediately appealed by all the authorities involved, and then by Sinangoe and their ally in the Defensoria del Pueblo, who seek an even tougher verdict recognizing that rights to health, water and a clean environment had also been violated. The case will be brought before a provincial judge in August, 2018.

The free, prior and informed consent loophole

Like in many places around the world, the Ecuadorian government has a mining claim system built to facilitate any interested party in purchasing cheap concessions— maximizing foreign interests and accelerating the approval process. Although both Ecuador’s Mining Act and the Constitution recognize the need for Free, Prior and Informed Consent from stakeholder communities for mining operations, it is still mostly a theoretical concept ignored by Ecuadorian agencies. Hence Sinangoe’s lawsuit. According to the experts heard over the course of the legal process, the Mining ministry leaves the “consultation” to the mining company or the concession owners themselves, which in turn have no legal obligation to consult with local people, and often will perform their “consultation” through a phone call or by handing out a simple information pamphlet. In the case of Sinangoe, it was when machines started tearing up the riverbed of the Aguarico looking for gold that the community learned about the new concessions.

The entire length of the Kofan River, a symbolic water body that crosses Sinangoe’s land, has been sold to gold miners by the Ecuadorian authorities without prior and informed consent. Mining in this area would cause dramatic environmental and cultural damage.

The Environment ministry, on the other end, stipulated in the courtroom that it is not responsible for consulting with communities impacted by mining. Interestingly, according to the Mining Act, the Environment Ministry needs to grant environmental licenses before operations can begin, unless the granting process takes more than 6 months, in which case – as unbelievable as this is – the permits are automatically granted to the operators. So basically, via a very simple bureaucratic process involving nothing more than paperwork, a mining operator can very quickly obtain 20 to 25-year land claims within 6 months, while the impacted communities living downstream haven’t even heard about the concessions. This is a loophole the judge described as a violation of the right to free, prior and informed consent, a verdict that will help many other communities facing the same threats in a country where gold mining is booming.

When rigorous community monitoring pays off

Throughout the lawsuit, the ministries’ lawyers vigorously tried to destroy Sinangoe’s evidence, credibility, ownership of and ancestral claims to the land. They downplayed the environmental damage documented by Sinangoe, claiming that the Kofan aren’t impacted by the mining operations because their land is on the other side of the river and that legal mining has minimal footprint on the environment. However, Sinangoe had done what will likely inspire many other communities: they had documented every step made by the miners through rigorous and systematic monitoring using high tech mapping, filming, archiving all evidence, and then they used legal tactics to pressure every single level of government to act to stop the operations. Systematic recording of all the different types of evidence helped build a solid case against a negligent concession-granting system.

Once in the courtroom, Sinangoe had accrued such a massive body of evidence of environmental damage and inaction on the part of the government that the judge requested a field inspection, a key event that helped him understand the scale of the damage already done, showed the deep connection the Kofan have with the area transformed into mining concessions, discredited the ministries’ arguments, and also allowed him to witness the sheer beauty of the area at risk.

A first legal victory, but the battle for land and rights still rages

To the officials sitting in their offices in Quito, these concessions were nothing more than coordinates and squares on a map, but to the Kofan who live across the riverbank, the area is a place imbued with life, history, sustenance, stories and so much more. To grant concessions without experiencing the place in and of itself, either through field visits or proper consultation with the people who inhabit and use the territory, is a transgression of the inherent value of sites so rich in history and biodiversity.

Sinangoe’s strength has been put to trial, and the community’s perseverance and conviction have provided them a first legal victory and attracted support from various indigenous and human rights organization across the country. With all ministries involved appealing the judgment, the Kofan will need more strength and support to navigate the next wave of legal governmental intimidation.

Sign the pledge in support of Sinangoe and stay tuned for more on our work to defend rights, lands and life in the Amazon.

List of chronicles in our series on Sinangoe:

Hit & Run from Illegal Miners

The “fluorescent” orange water coming out of the ground and flowing towards the pristine headwaters of the Aguarico River smells like a mix of sulfur and dead animals. The landscape has been ravaged, the jungle is gone, the ground has been turned inside-out, and the Provincial Prosecutor looking at the scene has trouble hiding his discomfort in front of such obvious evidence of illegal mining. This authority, the highest in the Northern Ecuadorian Amazon, is part of a delegation of the Environmental Police, the Ministry of Environment, the Ministry of Mining and the Ecuadorian Mining Regulation Agency who joined the Kofan land patrol of Sinangoe in a field visit where illegal miners had been wreaking havoc for 5 months already in this remote corner of the Amazon without being caught or sanctioned by authorities.

Alex Lucitante, a Kofan leader and human rights defender from the Ceibo Alliance, shows the Provincial Prosecutor and Ecuador’s Environmental Police a contaminated creek coming from illegal mining heading towards the Aguarico River.

Alex Lucitante, a Kofan leader and human rights defender from the Ceibo Alliance, shows the Provincial Prosecutor and Ecuador’s Environmental Police a contaminated creek coming from illegal mining heading towards the Aguarico River.

After a quick boat ride against the Aguarico’s treacherous white waters, the delegation has come to a full stop on a site that only a week ago was teaming with goldminers, excavators and water pumps. Sinangoe’s land patrol, with the support of Amazon Frontlines and the Ceibo Alliance, have found out in recent months that more than 70% of the mining operations were conducted outside of the mining concession granted by the Mining Regulation Agency back in February 2018. While the authorities observe the scene, the Kofan land rangers point to the areas where the mining camps were located the last time they had come to do their weekly patrol, but this time, only garbage and a leftover fire camp could be seen.

Described in a previous blog as a new gold rush area, the headwaters of the Aguarico have been divided into more than 30 000 hectares of mining concessions without any free, prior and informed consent from the Kofan Nation or any of the impacted communities, triggering a vast movement of solidarity and support to Sinangoe by other affected indigenous Nations living downstream. On the site, signs of illegal use of chemicals are obvious where open pools have been left untouched, those holes a clue of gold mining likely utilizing cyanide on this very site the week before, giving the riverbank a disquieting look. Along with my Kofan colleagues, we quickly come to the conclusion that the miners in the area have fled a while back, taking their digging toys with them once the news of an environmental inspection had spread like wildfire in this gold-boom area at the foothill of the Andes.

Open pools have been left untouched in an area that was teaming with miners a week before the visit. Authorities are seen inspecting one of the site on this drone clip.

Open pools have been left untouched in an area that was teaming with miners a week before the visit. Authorities are seen inspecting one of the site on this drone clip.

Pulling the government by the ears

The reason why this group of more than 20 representatives from various ministries and agencies are roasting under the Amazonian sun is not just because multiple Ecuadorian and International laws have been violated. Nor is it because the water of thousands of people living downstream is under threat from these illegal activities. In fact, the only reason we are all there together looking at the disastrous footprint of this early gold rush is because the Kofan have stood up for their land, documented every move made by the illegal miners, and then pressured every single level of government to act to stop this environmental and human rights nightmare immediately.

Flying the drone has allowed our team and the Kofan people of Sinangoe to detect and monitor the illegal miners in remote areas of the Ecuadorian Amazon. In this picture, the government authorities take a glimpse at the scene from the air through goggles.

With rigorous and systematic monitoring of every move from the miners – mapping, filming and documenting every step – the Kofan people of Sinangoe were able to demonstrate the illegality of the activities and force the Ecuadorian government to act, a first victory in a battle for the safeguard of their land. This comes after years of work for the Kofan who have decided to set in place their own indigenous law and their proper land patrol in order to detect, block and denounce any extractive activities inside their ancestral land. In the struggle to protect the Amazon, Sinangoe demonstrates the importance of indigenous-led land control in order to effectively avoid deforestation, forest degradation and poaching. Now that the authorities have finally seen the mess the Kofan have been denouncing for months, the community is waiting for action from the Prosecutor and the various ministries hoping they lead to canceling once and for all the dozens of mining concessions that have been granted in the area over the past months, and punishment for the mining companies that have operated against the law.

Damage is done, but the worst has been avoided

Over the course of 5 months of illegal mining, the trespassers have built a 2-kilometer road into pristine rainforest- opening Sinangoe’s ancestral land to more invasion. They have deforested over 15 hectares of forest, dug out countless pools, created landslides that have transformed the landscape, installed over 10 makeshift mining camps, modified the course of the Aguarico River, changed its color and turbidity and likely released a large amount of mercury and cyanide into the headwaters of this crucial Amazonian river. This neurotoxic heavy metal may cause health issues for dozens of riverine communities, contaminating the food chain for decades and accumulating into the fish those communities feed on every day.

Digging for gold with heavy machinery in the Amazon takes a heavy toll on the environment and the health of its inhabitants.

Nefarious as these impacts are, the worst has thankfully been avoided. Knowing how bad illegal gold mining in the Amazon can get pushed us to work rigorously, hard and fast to avoid the worst-case scenario. Those ⁓30 000 hectares of mining concessions have been granted for the next 25 years inside and on the borders of ancestral Kofan lands in the headwaters of the Aguarico River, an environmental bomb if it is exploited. More than ever Sinangoe needs support in order to make sure these concessions are canceled, and environmental restoration begins so the land can heal. The community has been discussing possible legal action with Ecuador’s Defensoria del Pueblo- a public institution that defends citizens’ rights- and either with them or without them will be taking legal action to protect their territory, and halt mining in the area.

These are very positive signs which needs to be reinforced. Please stand with Sinangoe to pressure the Ecuadorian government to cancel these mining concessions and respect the community’s right to free, prior and informed consent on any development activities affecting their lands, lives, or culture. By signing the pledge to #StandwithSinangoe, it allows you to add your voice to the movement, provide direct support to Sinangoe and stay informed on future important steps to protect Sinangoe’s land and rights.

List of chronicles in our series on Sinangoe: