8 Reasons The Landmark Ruling In Ecuador Signals Hope In The Struggle To Save Amazon Rainforest

This summer, a court in Ecuador issued a ruling with profound implications for the urgent fight to save the imperiled Amazon rainforest. The decision effectively blocked a planned government oil-auction that threatened half-a-million acres of some of the world’s most biodiverse primary rainforest. The broad outlines of the situation are sadly familiar to similar cases found throughout the Amazon region: In pursuit of foreign investment, the government sought to partner with foreign firms to develop large swaths of ecologically fragile rainforest. As is often the case, these forests were the ancestral lands of indigenous inhabitants who were not informed about — and did not approve — the arrival of industry on their territory.

The Waorani villagers-turned-plaintiffs have millennia deep roots in the region. They have seen the effects of oil blocks in other parts of the Ecuadorian Amazon, and knew that the planned auction threatened their survival and way of life. They also knew their rights: Like all indigenous peoples, they hold an internationally recognized right to informed consent when it comes to the “development” of their ancestral lands. When indigenous people fight to defend and enforce these rights, they are protecting their future and ours. The fate of the global climate hinges on empowering the indigenous peoples who help preserve nearly a quarter of the Amazon across seven nations, and who represent a powerful buffer against the destruction of a biosphere that regulates our planet’s flows of oxygen, carbon and freshwater.

Below are eight important lessons of this historic victory.

1) Healthy Cultures, Healthy Forests

The Waorani people are legendary hunter-harvesters of the southcentral Ecuadorian Amazon. For unknown centuries before their contact by missionaries in the 1960s, they lived in harmony with and preserved their rainforest home. They developed a rich culture marked by high craftsmanship and artistry, profound spirituality and a sophisticated understanding of the natural world and its complex systems of plant and animal life.

The Waorani and hundreds of other Amazonian indigenous cultures have been under enormous strain since the arrival of industry in the last century. Indeed, it is impossible to separate the physical pollution of the rainforest from the cultural disruption experienced by the people who live there. The relation between them is not causal, but cyclical: The growth of oil roads, mono-crops and mining jeopardizes indigenous peoples’ ability to survive off the land sustainably and in balance with the forest. It creates a dynamic that forces indigenous youth to abandon tradition and find work in the very industries that threaten their forest homes. The Waorani victory is important not only because it protects trees, but because it protects the culture that can continue to protect trees for centuries to come.

2) Defining the Narrative: Maps, Technology, Stories

The fate of the rainforest will be determined by how the world chooses to see it and conceive of its riches. Is the Amazon basin merely a green mass of undifferentiated land, crisscrossed by hundreds of unremarkable rivers? Is it a grid of resource concessions, notable for what’s under the ground, and convertible into currencies and value on international commodity markets? Or is the Amazon a tapestry of delicate and overlapping systems containing immeasurable biological, ecological and cultural treasures?

At their most basic level, these are competing stories, conflicting narratives, that begin with the maps that we use to represent the land. One of the ways the Waorani “won the narrative” was by using their own maps and telling their own stories. A territorial mapping project showed what the state and company maps left out — the turtle nesting grounds, the sacred sites, the ways the rivers fed the forest and each other. Through this and other tools — drone videos, testimonies, camera-trap images, even selfies — they illustrated the many ways that their culture, and everything it protected, is more precious than oil and greed. They also showed how a hunter-harvester people can leverage technology and social media on their own terms to challenge a mighty industry and capture the imagination of global civil society.

3) The Power of Legal Precedent

Rights enshrined in international laws and national constitutions are not worth their ink without enforcement. As with any laws, they are more likely to be enforced when they rest on firm precedent, locally and around the world. For too many years, the Waorani have seen the Ecuadorean government ignore their constitutional and international obligations to inform and acquire consent, and allow companies to pollute indigenous lands.

“We are Waorani and we have always lived in the Amazon rainforest. For thousands of years we have defended our territory from trespassers. Now we are fighting with our words and papers. We never knew the government wanted to extract oil from our lands. We, Pikenanis, are never going to sell our territory to the oil companies. We want to live well in our territory.”

– Memo Yahuiga Ahua Api, Pekinani (traditional leader)

“We are Waorani and we have always lived in the Amazon rainforest. For thousands of years we have defended our territory from trespassers. Now we are fighting with our words and papers. We never knew the government wanted to extract oil from our lands. We, Pikenanis, are never going to sell our territory to the oil companies. We want to live well in our territory.”

– Memo Yahuiga Ahua Api, Pekinani (traditional leader)

Because the Waorani demanded the government respect the law and the constitution, indigenous peoples across the Amazon can now draw inspiration and tactical lessons from Waorani legal success in linking the right to self-determination to the right to free, prior, and informed consultation. Its example puts the country and the region one step further towards redefining the legal framework for indigenous rights.

Although the first battle has been won, the struggle is ongoing. The Ecuadorian government is still seeking to auction seven million acres in the country’s central rainforest to oil companies.

4) Climate Change & Interconnectedness

The Waorani victory is a victory for the climate: it keeps 500,000 acres of trees working as carbon vacuums, and prevents the pumping of millions of gallons of crude oil that would have been shipped to California for refining and distribution to gas stations across the United States. In aggregate, it is estimated that over the next ten years the Waorani victory will have avoided approximately 19.0 million metric tons of CO₂ emissions – or the equivalent of the greenhouse gases emitted from roughly 4 million passenger cars in one year.

After the oceans, the rainforests are the world’s most important carbon sinks, a sprawling continent’s worth of vegetation that absorbs and keeps carbon out of the atmosphere for hundreds of years. As the traditional inhabitants and defenders of this carbon sink, indigenous communities are the “secret weapon” in its defense, according to a growing body of research. A report by a group of leading research centers estimates that indigenous lands cover around a quarter of the world’s above-ground tropical carbon sinks.

The importance of the Amazon system extends beyond carbon. Its hydrological cycle involves more than one-fifth of the planet’s freshwater supply, and any decline in rainfall and evapotranspiration in the Amazon — the consequence of deforestation and contamination — has far-reaching effects, including drought in breadbaskets throughout the hemisphere and less river-feeding snowpack in the mountains of the pacific northwest.

5) Women in Front

The Waorani struggle involved three generations of women fighting to protect their culture, territories and sources of food and fresh water. Dozens of Waorani women participated in the court proceedings, and led the media events surrounding the hearing. They arrived bearing examples of traditional Waorani culture and craftsmanship — palm-woven baskets, clay pots and food grown in traditional gardens. When the women felt they were being disrespected by court and government officials, they halted the insults by breaking out into spontaneous song. All of this helped capture the imagination of the world with their spirit and their conviction and courage.

“This victory is a dream come true. It means that our future generations can continue to live freely in a healthy and pristine forest, with clean water and pure air. I always wanted to protect these lands for the future generations, as my ancestors did for me! It is the legacy for my grandchildren. This belongs to them!”

– Omanca Enquiri, Pekinani (traditional leader)

One of the lead plaintiffs in the case is Nemonte Nenquimo, a Waorani mother and president of the Waorani communities on the Pastaza river. “We are the caretakers of the forest and we will continue defending it as our ancestors have done for thousands of years,” Nenquimo told reporters outside the courtroom during this summer’s hearing. “As women, we are fighting for our children, for our families, for our communities and for our Mother Earth. We will never allow the oil companies to enter our territory. Our forest is not for sale and this is our decision”.

6) Protecting Rivers and Water

Life in the Amazon is lived on rivers. From fishing to bathing to providing drinking water, the rivers are the central arteries of everyday life. Because all of the rivers in the Amazon flow from or into other rivers — and are often located in floodplains — it is all but impossible to isolate or contain contamination. This is made tragically clear in the legacy of the U.S. oil company Texaco (now Chevron) which in the 1960s won a government contract to develop the region’s oil deposits. Disregarding the health of the forests and the local indigenous people, the company dumped waste and spilled oil wantonly throughout the forest and into its rivers. Many local indigenous people fell ill and died from consuming toxic material that sometimes appeared as thick sludge on the river, and other times was invisible, but no less dangerous to those who consumed it through the water, produce grown on contaminated soils, and the wider food chain. Today, many communities in eastern Ecuador cannot drink from rivers their ancestors used for countless generations. The contamination of the region is not historical, but ongoing. Though Chevron no longer operates in the region, regional and Chinese firms continue to engage in oil production at the invitation of the Ecuadorean government.

This is the crucial, local context for the Waorani victory, and explains why the villagers refused to allow further destruction of the area’s fresh water sources. Their refusal reflects a global movement — seen throughout Latin America, Africa, and Asia, all the way to Standing Rock in the U.S. — to both defend indigenous rights and lead by example toward a broader and deeper respect for nature as the sacred source of all life.

7) Wildlife and Biodiversity

It is said that the Amazon invites cliché and resists hyperbole. Indeed, it is difficult to overstate the bounty of the Amazon’s plant and animal life. Accounting for a tenth of all known species on the planet, the Amazon is an ecosystem without equal. It is also an ecosystem full of mysteries yet to be discovered. Much of the modern pharmacopeia derives from Amazonian plants, and longstanding medical mysteries may yet be solved by researching the flora of a healthy forest.

“The forest is rich and provides us with everything we need.

We are not poor, we are rich in resources and we will not allow anyone

to come and destroy our home because it is our life”

– Awane Ahua, Pekinani (traditional leader)

“The forest is rich and provides us with everything we need.We are not poor, we are rich in resources and we will not allow anyone to come and destroy our home because it is our life”

– Awane Ahua, Pekinani (traditional leader)

The northern Ecuadorian Amazon is a tragic example of how the delicate web of life in the rainforest can be ruined within a generation by the arrival of extractive industry. In 1970, the area around Lago Agrio, the region’s biggest city, was one of healthy rivers and forests, full of animal and aquatic life. Now, in villages along the Putamayo and Aguarico, the water is undrinkable and many ancestral hunting grounds are bare, polluted, and bisected by roads. Fragmentation is a major threat to biodversity and wildlife, and the government’s proposed oil blocks would pollute an important biological corridor running across the wider region.

The species-level stakes of Amazon protection were highlighted this May with the release of a landmark United Nations’ report on biodiversity. The report warned that unless critical ecosystems are protected, as many as one million species are threatened with near-term extinction. The Waorani have won a battle for themselves, their children and the planet, but also for the jaguars, the monkeys, the birds, and the ants.

8) Union of Indigenous Nations

The indigenous nations of the Ecuadorian Amazon understand themselves to share a common struggle. Collectively they are the guardians of 70% of the entire Ecuadorian Amazon rainforest. Many of these peoples joined the Waorani in solidarity outside the courtroom, traveling from distant communities in the country’s north and south. They marched with the Waorani in the streets; they submitted amicus briefs; and they returned to their communities to share what they had learned to better organize for the future. “We have united with our Waorani brothers and sisters because we share the same struggle and dream: to protect our forest and to continue being who we are, as indigenous peoples,” said Alex Lucitante, a Kofan leader. “We will continue to unite forces and build strength between our peoples to resist the threats to our territories. Without unity, there can be no triumph.”

"Indigenous Nations across the Amazon and the world must band together to protect our homes."

- Oswando Nenquimo

This model of multi-nation mobilization and solidarity — across Ecuador and the entire Amazon — will be crucial to defeating the extraction at-all-costs paradigm that threatens the region. The Waorani alliance was a powerful demonstration of this. Now the challenge is to scale up the precedent and further empower those defending the seven million acres of indigenous land still targeted by the government and the oil industry.

Will you stand with the Amazon’s oldest guardians to protect a forest we all depend upon at this critical moment?

From Big Oil to Palm Oil: Transforming the Ecuadorian Amazon into Monocultures

For decades, the Ecuadorian Amazon has been the epicenter of one of the most polluting oil operations of all times. The oil boom initiated by Texaco in the 1970s is well known as the main driver of deforestation in this strikingly biodiverse forest, home to many indigenous nations. Once the roads have been built for pipelines, oil wells and oil pits, wave after wave of colonists come to clear the forest and establish pastures and agriculture. This drastic conversion has resulted in the loss of over 1 million acres of pristine rainforest since 1990.

However, over the past two decades, one “colonist” has been increasingly expanding in the Ecuadorian Amazon, and without much attention from the public: the African palm oil industry. Radically transforming extremely rich ecosystem into monocultures over large tracts of land, the palm oil industry now occupies over 160 000 acres in the Amazonian provinces of Sucumbíos and Orellana alone, and continues to encroach further and further into indigenous ancestral lands.

A risky, radical land change

Palm oil plantations have more than doubled in Latin America since 2001, and Ecuador is now amongst the top 10 producing countries in the world. One needs to fly over Amazonian palm plantations in order to fully grasp the impact of such large operations. In the province of Sucumbíos, in the Northern Ecuadorian Amazon, blocks of forest covering more than 30 000 football pitches have been converted into palm monocultures.

In this area of the Amazon, two main players control the market: Palmar del Rio, and Palmeras del Ecuador – a subsidiary of Danec S.A. These Ecuadorian companies own over 50% of all palm plantations in the region and buy in bulk from the vast majority of the smaller producers. Interestingly, despite its constant growth, palm oil production in the Amazon is not very profitable, and thus depends on massive subsidies and large-scale operations in order to be successful.

Over 160 000 acres of the Ecuadorian Amazonian rainforest have now been converted into African Palm plantations

One of the main challenges for the palm oil producers is the need for large amounts of fertilizers and pesticides in order to improve their crop yield, to compensate for the nutrient loss resulting from deforestation, and to control insect and fungus infestations. Companies also have to invest massively in the development of new hybrid trees that can resist infestations. These three necessities – pesticides, fertilizers and research and development – require the investment of millions of dollars each year. According to data (2013) from the Ecuadorian government, a palm plantation owner spends on average seven times more money on fertilization and insect and disease control (702$/hectare) than on the actual harvest (100$/hectare) in the first year of harvest.

The fact is, replacing one of the richest and most complex forests in the world with a single-plant system involves high risks for insect and fungus outbreaks, a reality which the Ecuadorian company Palmar del Rio, like many others, learned the hard way. Back in 1998, after clearing nearly 25 000 acres of Amazonian rainforest for its plantation near the town of Coca, this agribusiness lost every single palm tree due to a bud rot infestation, a widespread disease which has affected, and still threatens, hundreds of thousands of acres of palm plantations in Latin America.

Living downstream

The Shushufindi River, surrounded by the biggest African Palm plantations in the Ecuadorian Amazon, is also the main source of fish for the indigenous Secoya community of Bella Vista. Concerned by the chemicals used by the palm oil industry, the community is working with Amazon Frontlines and their indigenous partners of the Ceibo Alliance to measure the amounts of pesticides found in common fish eaten on a daily basis.

Despite these high risks, the loss of primary forests to palm oil production is increasing in the Amazon, and the consequences go far beyond deforestation, biodiversity loss and carbon emissions. Almost all Amazonian palm plantations in Ecuador are located upstream from ancestral Secoya and Siona lands. Streams and rivers crossing entire plantations and accumulating herbicides, insecticides, fungicides and fertilizers also pass through communities, contaminating essential drinking and bathing water, as well as the fish they eat and the soils they use. When you depend upon the forest and river for survival, a 50 000-acre palm plantation is not a good neighbour to have.

Facing these threats to their health and safety, many Siona and Secoya communities have decided to work with Amazon Frontlines and the Ceibo Alliance to monitor contamination levels in the fish they catch. In mid-2018, our teams initiated a pilot project measuring pesticides, heavy metals and hydrocarbon levels in small local fish and secondary catchments from the Shushufindi River. Through our monitoring program, we hope to empower communities by allowing them to gain vital information about the changes and threats to their surroundings, and gather robust evidence which they can use in order to advocate for their rights for greater territorial protection.

Tapping into the Amazon’s Rain

For many of you who are reading this Chronicle, access to potable water, directly into your home, is a given. For most people in the world, though, this simply is not the case. In fact, according to the United Nations billions of people live without access to safe water. Billions. Among them are the indigenous communities of the Ecuadorian Amazonian rainforest where, despite the fact that water abounds, the rivers and streams have been nearly ubiquitously contaminated by oil, rendering the once pristine waters undrinkable. At the same time, ballooning population combined with inadequate sanitation has led to a rise in parasites carried by water.

From 2012 to 2018, Amazon Frontlines and its partner organization Ceibo Alliance provided domestic rainwater harvesting systems to 1164 households in 78 communities of the Northeastern Ecuadorian Amazon benefiting over 6000 people living downriver from the oil fields. In this Chronicle, we will learn more about the water-related health problems that indigenous people in the Amazon face and how domestic rainwater harvesting systems are helping.

Tainting the Amazon's surface water

In the period from 2005 to 2015 alone, oil companies released over 350,000 barrels of crude oil into the rivers, streams and soils of the Ecuadorian Amazon, amounting to an average of 4000 barrels of a toxic chemical mix, including heavy metals and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, released every day into the environment. Some hydrocarbons are known carcinogens (IARC, 2015). A study in an oil-producing region of Peru examined nearly 3000 river water samples and found that a significant number of them did not meet Peruvian water quality standards for a variety of metals. The authors conclude, “that spillage of produced water in Peruvian Amazon rivers placed at risk indigenous population and wildlife during several decades. Furthermore, the impact of such activities in the headwaters of the Amazon extended well beyond the boundaries of oil concessions and national borders, which should be taken into consideration when evaluating large scale anthropogenic impacts in the Amazon” (Yusta-García 2017, abstract).

Co-founders of the Ceibo Alliance show evidence of oil contamination in the northern Ecuadorian Amazon. From left to right: Alicia Salazar of the Siona nation, Nemonte Nenquimo of the Waorani nation, and Flor Tangoy of the Siona nation.

Concurrently, African palm plantations have led to the deforestation of an equivalent of 100 000 soccer fields and the use of a large quantity of pesticides and fertilizers, some of which end up in the local waterways. Some pesticides are considered probable carcinogens (IARC, 2015).

Over the past half-century, the Ecuadorian Amazon has been crisscrossed by more than 9500 km of roads – or 1.5 times the Earth’s radius – built to connect the more than 3430 oil wells to market via pipeline. The construction of a proposed road in a remote region of the Peruvian Amazon was found to have disproportionately negative impacts on the drinking water quality (sediment retention and nitrogen and phosphorus regulation) of nearby indigenous communities (Mandel et al. 2015).

Access roads entice colonists to set up small farms, resulting in the deforestation of vast tracts of land. Amazonian soils contain large amounts of naturally occurring mercury, accumulated there over centuries of nearby volcanic activity (Mainville et al. 2006). Mercury exists in the soils in a harmless form, but once soils erode into waterways following deforestation, the mercury is converted into a toxic form, easily entering the aquatic food chain and humans via fish consumption (Webb et al. 2004). Illegal gold mining, booming in certain areas of the Amazon, can also be an important source of mercury to aquatic ecosystems (Akagi et al., 1995).

From Pristine to Parasite-infested

Sipping your chlorinated water, fresh from the tap, you might think, “Who would drink straight from the river?” Yet, for millennia, this was the main source of water in the Amazon and it supported thriving civilizations. However, nowadays, the water is teeming with harmful microscopic life that your eyes can’t see but that your intestines detect. Studies show that the current high parasite levels are not the baseline for Amazonian waterways.

Several early studies conducted in the 1980s, just as the population of the Ecuadorian Amazon was exploding, show that the indigenous people, who had no other source of water than the same streams and rivers that their ancestors drank from, had relatively low parasite levels. “Before sustained contact, the Huaorani had practically no intestinal parasites due to drinking from feeder streams with headwaters rarely visited by outsiders; however, within 3 years of contact their parasite loads were nearly equal to those of neighboring groups” (Davis and Yost, 1983 in Houck et al., 2013).

Benefice et al. (1990) showed that parasitic infestation rates among settlers were significantly higher than in the Siona-Secoya communities and attributed this partly to the readily available and good quality water running through indigenous communities.

Waorani women in their ancestral territory, Pastaza Province, Ecuadorian Amazon

A recent study conducted in Bolivia found that the Tsimane’ people appear to adapt to poor water quality by eating more fruit (Rosinger and Tanner, 2015). They found that 50% of their total water intake came from fruit and that each percent increase in water consumed from food was associated with a decrease in gastrointestinal illness. “Both total water intake and percentage of water from foods were higher than averages in industrialized countries. These findings suggest that people without access to clean water may rely on water-rich foods as a dietary adaptation to reduce pathogen exposures” (Rosinger and Tanner, 2015; abstract). Unfortunately, some of the same processes that are leading to deteriorating water quality are also reducing people’s access to flourishing forests and their succulent produce.

Amazonian ecosystems had their own mechanisms for keeping parasite levels low. The problem has arisen recently primarily because of swelling population levels and inadequate sanitation. The ecosystem has quite simply become overloaded with feces. At the same time, current land-use practices are diminishing the ecosystem’s ability to rid water of existing parasites. Healthy forests, intact soils and rich decomposer biodiversity can provide physical barriers to substances that hold high levels of parasites from getting into waterways. Without them, parasites can get the upper hand. Additionally, a recent paper has shown that coliforms, and potentially other harmful water-borne pathogens, proliferate in the presence of hydrocarbons (Khanafer et al. 2017).

Climate change is leading to flooding in certain regions and drought in others. Both affect water security. In Bolivia, it was found that incidence of diarrhea related to pathogens in the the water roughly doubled following a historic flood in 2014 (Rosinger 2017). Floods sweep away domestic animals and wildlife contaminating river water, while overflowing rivers seep into otherwise clean underground water sources.

In 2016, water, sanitation and hygiene (WSH) was responsible for 1.9% of the global burden of disease. The latest data available for Ecuador estimates the total WSH-related deaths at 88,200, or 3.9% of the deaths in 2004. In 2015, over 2 million Ecuadorians did not have access to improved water. Chronic diarrhea, especially in children, can lead to malnutrition (Buitron et al. 2004). Treatments for stomach complaints can sap scarce economic resources from families with limited revenue, forcing them to work longer hours, go without other essentials or exploit natural resources.

Provisioning Water from Rain

The United Nations named access to clean drinking water a basic human right in 2010. In that same year, 89 million people across the globe depended on rainwater as their main supply (WHO and UNICEF, 2012). Rainwater is largely free of impurities (World Health Organization, 2008). When properly installed and managed, Domestic Rainwater Harvesting (DRWH) Systems are considered inexpensive and low-tech; and vastly superior to most alternatives, such as surface water. Bearing in mind the benefits of rainwater harvesting, expanding capacity in developing countries has been set as a new World Health Organization goal (6.a) (WHO and UNICEF, 2017; p.7).

Most studies have reported levels below maximum permissible concentrations for metals, hydrocarbons and pesticides in rain-harvested water (Abbasi & Abbasi, 2011). Women in the Amazon who use surface water were found to have twice the amount of mercury and hydrocarbons in their urine as women who use rainwater (Webb et al. 2016; 2017).

Considering the abundance of rain in the Amazon and deteriorating water quality as a result of industrial extraction processes and demographic changes, Amazon Frontlines and the Ceibo Alliance, along with our partners Rainforest Fund and Saving an Angel, designed a water provisioning project based on the installation of domestic rainwater harvesting systems. Over the past seven years, the ClearWater project has provided clean and free drinking water to indigenous peoples of the Kofan, Secoya, Siona, and Waorani nations in the Ecuadorian Amazon, one of the world’s most infamous oil-related disaster areas.

In order to ensure that the 6000-plus people serviced by ClearWater’s rainwater harvesting systems were indeed benefiting from the water provided by the ClearWater project, we conducted an evaluation of water quality, integrating observations from in-depth interviews with users in the indigenous communities.

“How safe is the water? How has your life changed since you got potable water? Have you observed any changes in your health?” The Ceibo Alliance’s Scientific Advisor, Jena Webb, and Amazon Frontlines’ Monitoring Lead, Nicolas Mainville, led an investigation to find out.

Here are some of the most important findings:

· Drinking water samples had no detectable levels of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) or heavy metals such as mercury and lead.

· 86% of people reported improved digestive health (reduced diarrhea, vomiting and stomach pain) since the installation of the systems.

· 85% of systems had ideal water quality as indicated by fecal coliform levels.

· Water from alternative sources (rivers, streams and springs) had significantly lower water quality as indicated by high levels of fecal coliform.

· One hundred percent of the respondents were satisfied with the taste of the water and the functioning of their system.

The qualitative analysis showed a high level of satisfaction with the water and the systems. Comments pointed to improvements in health and workload, with the system reducing the number of hours and the effort required to collect water. This is especially crucial with respect to women’s work, health and well-being as this task most often falls to women and girls. World-wide, eight out of ten households in which water is off-premises rely on women and girls to carry out the difficult, and sometimes dangerous, task of water collection. In the water security study carried out in the Bolivian Amazon, 24% of women (compared to only 7% of men) reported having been injured in the month prior while fetching water (Rosinger 2018).

“The tanks make it easier because we have water right here. Before we had the tanks, we had to go down to the river, lug up buckets, and go back, up and down, often. We had more work. But now, no, we have the tank right at the foot of the house. I used to get tired.”- Anonymous woman interviewed as part of our evaluation on the ClearWater Domestic rainwater harvesting systems

So, now 1164 households in 78 communities of the Ecuadorian Amazon also have running water, right at their kitchen door, thanks to the ClearWater project. This water contains no chlorine, but the vast majority of it is just as clean as that coming out of the faucet in any home in a developed nation. Clean drinking water is the most fundamental of basic needs and a prerequisite for thriving and resilient communities. Our hope in conducting this project has been to contribute to these communities’ wellbeing and their capacity to defend their forest homes. Our hope in communicating about the evaluation is to build out solutions and lessons for other indigenous villages affected by oil and water of sub-standard quality on how to construct rainwater harvesting systems and maintain them. As oil companies continue to push further into the forest, this urgent work continues both here in the Ecuadorian Amazon and elsewhere.

Find out more about this powerful indigenous-led and community-based project, and join the movement for a healthy future in the Amazon.

References

Abbasi, T. and S. A. Abbasi (2011). “Sources of pollution in rooftop rainwater harvesting systems and their control.” Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology 41(23): 2097-2167. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10643389.2010.497438

Akagi, H., O. Malm, Y. Kinjo, M. Harada, F. J. P. Branches, W. C. Pfeiffer and H. Kato (1995). “Methylmercury pollution in the Amazon, Brazil.” Science of The Total Environment 175(2): 85-95.https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0048969795049053

Buitron, D., A. Hurtig and M. San Sebastian (2004). “Nutritional status of Naporuna children under five in the Amazon region of Ecuador.” Rev Panam Salud Publica 15(3): 151-159. https://www.scielosp.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1020-49892004000300003&lang=en

Davis, E. W. and J. A. Yost (1983). “The ethnomedicine of the waorani of Amazonian Ecuador.” Journal of Ethnopharmacology 9(2): 273-297. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0378874183900363

Houck, K., V. Sorensen Mark, F. Lu, D. Alban, K. Alvarez, D. Hidobro, C. Doljanin and I. Ona Ana (2013). “The effects of market integration on childhood growth and nutritional status: The dual burden of under‐ and over‐nutrition in the Northern Ecuadorian Amazon.” American Journal of Human Biology 25(4): 524-533. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/ajhb.22404

International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). Agents Classified by the IARC Monographs, Volumes 1 – 114. 2015. https://monographs.iarc.fr/agents-classified-by-the-iarc/

Khanafer, M., H. Al-Awadhi and S. Radwan (2017). “Coliform Bacteria for Bioremediation of Waste Hydrocarbons.” BioMed research international 2017: 1838072-1838072. https://www.hindawi.com/journals/bmri/2017/1838072/

Mainville, N., J. Webb, M. Lucotte, R. Davidson, O. Betancourt, E. Cueva and D. Mergler (2006). “Decrease of soil fertility and release of mercury following deforestation in the Andean Amazon, Napo River Valley, Ecuador.” Science of the Total Environment 368: 88-98. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0048969705006546

Mandle, L., H. Tallis, L. Sotomayor and A. L. Vogl (2015). “Who loses? Tracking ecosystem service redistribution from road development and mitigation in the Peruvian Amazon.” Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 13(6): 309-315. https://esajournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1890/140337

Rosinger, A. and S. Tanner (2015). “Water from fruit or the river? Examining hydration strategies and gastrointestinal illness among Tsimane’ adults in the Bolivian Amazon.” Public Health Nutrition 18(6): 1098-1108. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/public-health-nutrition/article/water-from-fruit-or-the-river-examining-hydration-strategies-and-gastrointestinal-illness-among-tsimane-adults-in-the-bolivian-amazon/96F7D9B8716DC45553D8CBC0B4122C11

Rosinger, A. Y. (2018). “Household water insecurity after a historic flood: Diarrhea and dehydration in the Bolivian Amazon.” Social Science & Medicine 197: 192-202. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0277953617307463?via%3Dihub

Webb, J., N. Mainville, D. Mergler, M. Lucotte, O. Betancourt, R. Davidson, E. Cueva and E. Quizhpe (2004). “Mercury in fish-eating communities of the Andean Amazon, Napo River Valley, Ecuador.” EcoHealth 1(suppl. 2): 59-71. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10393-004-0063-0

Webb, J., O. T. Coomes, D. Mergler and N. Ross (2016). “Mercury Concentrations in Urine of Amerindian Populations Near Oil Fields in the Peruvian and Ecuadorian Amazon.” Environmental Research 151: 344-350. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0013935116303279

Webb, J., O. T. Coomes, D. Mergler and N. A. Ross (2017). “Levels of 1-hydroxypyrene in urine of people living in an oil producing region of the Andean Amazon (Ecuador and Peru).” International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health 91(1): 105-115. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs00420-017-1258-3

World Health Organization. (2008) Rainwater Harvesting. Chapter 6.11 In: Guidelines for Drinking-water Quality, Second Addendum to the 3rd Edition. Geneva. https://www.who.int/water_sanitation_health/dwq/fulltext.pdfWorld Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) (2012) Progress on drinking water and sanitation. 2012 Update WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply and Sanitation. Geneva. https://reliefweb.int/report/world/progress-drinking-water-and-sanitation-2012

World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) (2017) Progress on Drinking Water, Sanitation and Hygiene: 2017 Update and SDG Baselines. Geneva. https://www.unicef.org/publications/index_96611.html

Yusta-García, R., M. Orta-Martínez, P. Mayor, C. González-Crespo and A. Rosell-Melé (2017). “Water contamination from oil extraction activities in Northern Peruvian Amazonian rivers.” Environmental Pollution 225: 370-380. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0269749116321674?via%3Dihub

List of Chronicles in our Health on the Frontlines series:

Nothing found.

Indigenous Nations Unite To Defend Waorani Victory

In the wake of the Waorani people’s recent historic victory, which protects half a million acres of their rainforest territory in Ecuador’s Amazon from oil drilling and sets a key legal precedent for indigenous rights, the government declared that it would appeal the court’s decision. This move poses an imminent threat to indigenous autonomy and the conservation of the Amazon rainforest, the lungs of our planet.

Last week, in Ecuador’s capital city of Quito, the Waorani people spearheaded a mass mobilization, during which hundreds of indigenous peoples from nations including the Kichwa, Sapara, Andoa, Shiwiar, Achuar and Shuar, came together to protect the Waorani victory and to send a clear message to the government: respect indigenous rights.

Recent statements from the Ministry of Energy and Non-Renewable Resources aimed at pressuring the judiciary to overturn the ruling. “The Ecuadorian government has no right to decide over what happens in our territory. We are the ones who make the decisions over lands and lives. The government has every right to appeal and we are not afraid – whether we win or lose this legal case, we will continue to fight because our forest is our life”, affirmed Oswando Nenquimo, a young Waorani spokesperson and plaintiff for the case.

“We have defended our forest for thousands of years, and today we continue to fight”, declared Nemonte Nenquimo, Waorani leader and lead plaintiff outside the head offices of the Ministry of Energy and Non-Renewable Resources in Quito. “The government must listen to our voices and must respect our rights. Our territory is not for sale: this is our decision. How can the government put our lives at risk all in the name of the last drops of crude oil? I’m calling on everyone to stand with us and to unite with our movement: this struggle isn’t just of the Waorani people – it’s for everyone, it’s for our planet.”

Now is a critical time to ramp up support for the Waorani’s urgent struggle to protect the Amazon, and your voice counts. Share your favorite photograph and send a message to the the Ecuadorian government demanding respect for the court’s decision, and to show the judicial system that the world is watching. Together, we can defend indigenous rights in the Amazon!

The Waorani Resistance in Photos

For elders living in Waorani territory of Ecuador’s Pastaza Province, a ½ million acre roadless wilderness still untouched by the perils of oil, mining and logging, the forest contains nearly everything that is needed for a happy and healthy life.

▼ Here, Pava Yeti, an elder from the village of Kiwaro, makes a basket from palm leaves for harvesting and carrying wild fruits, such as petomo (ungurahua) and nontoka (peach palm).

The Waorani people’s knowledge of their tropical rainforest homeland is legendary. In this photograph, Memo Ahua, from the village of Akaro, uses the Winang plant to imitate the shrill whistling sound of a crying-baby-toucan. Tucked under his shoulder is a 3-meter blowgun made from the chonta palm, a black hardwood, wrapped in a fine leathery bark and sealed with beeswax.

Woven together by hundreds of miles of trails that connect birthplaces with burial grounds, gardens with villages, hunting camps with fishing holes, plant medicines with sacred sites, and backwoods creeks with big water rivers, Waorani elders know every nook and cranny of their immense rainforest home.

In the Oil Fields of the Amazon

Further to the east however, decades of oil extraction have converted thousands of acres of ancestral hunting grounds, fruit orchards and sacred sites into a patchwork of oil fields, logging camps, roads, and colonist settlements.

► In this picture, on the edge of Yasuni National Park famous for its rich biodiversity, a family of Waorani from the Via Pindo oil road walk back to their village along pipelines to avoid the hazards of speeding oil-company 18-wheelers.

And further to the north, in the borderlands with Colombia and Peru, more than a half-century of oil operations and colonization has devastated the ancestral lands of the Kofan, Siona and Secoya peoples.

▼ Here, Emergildo Criollo, a Kofan leader, recalls the first time he saw the oil company helicopter arriving in his people’s ancestral land. “Since then, the oil company has brought nothing but sickness and death to our people,” he tells Nemonte Nenquimo, leader of the Waorani people of Pastaza.

In 2012, the Ecuadorian Government announced plans to auction over 7 million acres of indigenous lands in the southcentral amazon to the oil industry.

Included in the oil auction was the newly denominated “Oil Block 22”, a half million acres of primary rainforest that the Waorani have called home for centuries.

Despite a slick government sponsored campaign to promote investment, many oil blocks, including Block 22, were not successfully sold at auction. Oil investors cited “risks” associated with community opposition and unattractive financial terms.

However, for the Waorani the “failed” oil auction was a warning. And a call to organize.

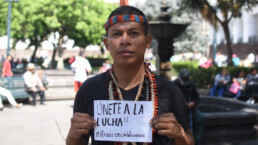

▼ In this photograph, youth leader Oswando Nenquimo reads a message to the Ecuadorian Government:

“We do not recognize what the government calls Oil Block 22. Our forest homeland is not an oil block. It is our life.”

As a strategy of resistance, from 2015-2018, Waorani youth and elders set out to document and demonstrate life in their territory by creating a “living map” of their connection to the land, using GPS, film, camera traps, drones, and a customized mapping program that allowed them to work offline in remote forest.

Whereas the maps of oil companies only show petroleum deposits and major rivers, the maps that the Waorani created tell the story of their people’s relationship with the plants, the trees, the water, and the animals.

▼ Their maps identify historic battle sites, ancient cave-carvings, jaguar trails, medicinal plants, animal reproductive zones, important fishing holes, creek-crossings, and sacred waterfalls.

▼ In this photograph, school kids in the village of Nemonpare display their drawings of what they like most about life in the forest.

In 2018, the Ecuadorian Government announced renewed plans to auction million of acres of the southcentral Amazon to the oil industry.

In a series of urgent region-wide assemblies the Waorani decided to take legal action to halt the sale of their lands.

▼ In a public hearing in the village of Nemonpare, the Ecuadorian Human Rights Ombudsman takes testimony from youth and elders in preparation for the lawsuit.

Dozens of hours of interviews revealed that the government’s “consultation process” relied on time-tested tactics of manipulation and deceit, and was designed to keep Waorani villagers in the dark about the potential impacts of oil operations in their territories.

“The government came to our village for an hour and promised us hospitals and schools. We didn’t know that they were planning on selling our land to the oil companies.”

− Wina Boyotai from Kiwaro ►

“For the government, the sale of our land was a foregone conclusion. They had already drawn up the plans and the maps. They didn’t come to consult us. They came to trick our people into signing a piece of paper. But we know we have rights, and we are ready to defend them.”

− Oswando Nenquimo from Nemonpare ►

Victory for the Waorani

On February 27, 2019, hundreds of Waorani villagers from “Oil Block 22” marched to the courthouse in the Amazonian frontier town of Puyo to file their landmark lawsuit against the Ecuadorian government. ►

▲ In the courthouse building, the lead plaintiffs wait to file their landmark lawsuit. From left to right, Memo, Omanka, Nemonte, Wina, and Dika.

THE VERDICT IS IN! VICTORY FOR THE WAORANI PEOPLE!

Back to the Forest

After the historic court ruling which protects a half-million acres of their ancestral land from oil drilling, the Waorani returned to their forest homes.

And walked freely in their forest.

The Waorani’s landmark legal victory protects their ancestral homeland from oil and sets a powerful precedent for other indigenous nations to do the same, but this watershed moment could be snatched away in the next two months by a legal appeal. The Ecuadorian judicial system is not immune to political influence, especially with millions of acres of “untapped oil reserves” at stake and the Government’s keen interest in undoing this powerful legal precedent for indigenous rights.

We must seize the momentum, and turn national and global attention into an even bigger victory for indigenous peoples, the Amazon and our climate.

Here’s what you can do today:

For elders living in Waorani territory of Ecuador’s Pastaza Province, a ½ million acre roadless wilderness still untouched by the perils of oil, mining and logging, the forest contains nearly everything that is needed for a happy and healthy life.

▼ Here, Pava Yeti, an elder from the village of Kiwaro, makes a basket from palm leaves for harvesting and carrying wild fruits, such as petomo (ungurahua) and nontoka (peach palm).

The Waorani people’s knowledge of their tropical rainforest homeland is legendary. ▼ In this photograph, Memo Ahua, from the village of Akaro, uses the Winang plant to imitate the shrill whistling sound of a crying-baby-toucan. Tucked under his shoulder is a 3-meter blowgun made from the chonta palm, a black hardwood, wrapped in a fine leathery bark and sealed with beeswax.

Woven together by hundreds of miles of trails that connect birthplaces with burial grounds, gardens with villages, hunting camps with fishing holes, plant medicines with sacred sites, and backwoods creeks with big water rivers, Waorani elders know every nook and cranny of their immense rainforest home.

In the Oil Fields of the Amazon

Further to the east however, decades of oil extraction have converted thousands of acres of ancestral hunting grounds, fruit orchards and sacred sites into a patchwork of oil fields, logging camps, roads, and colonist settlements. ▼ In this picture, on the edge of Yasuni National Park famous for its rich biodiversity, a family of Waorani from the Via Pindo oil road walk back to their village along pipelines to avoid the hazards of speeding oil-company 18-wheelers.

And further to the north, in the borderlands with Colombia and Peru, more than a half-century of oil operations and colonization has devastated the ancestral lands of the Kofan, Siona and Secoya peoples.

▼ Here, Emergildo Criollo, a Kofan leader, recalls the first time he saw the oil company helicopter arriving in his people’s ancestral land. “Since then, the oil company has brought nothing but sickness and death to our people,” he tells Nemonte Nenquimo, leader of the Waorani people of Pastaza.

▼ In these photographs, Waorani youth and elders visit the oil fields of Lago Agrio to learn firsthand from the Kofan, Siona and Secoya about the impacts of the oil industry.

Upon arriving at an oil platform outside the industry town of Shushufindi in Ecuador’s Amazon Waorani women sing to the oil well: “We walk lightly in the footsteps of our ancestors, we will not let you into our land.”

In 2012, the Ecuadorian Government announced plans to auction over 7 million acres of indigenous lands in the southcentral amazon to the oil industry.

Included in the oil auction was the newly denominated “Oil Block 22”, a half million acres of primary rainforest that the Waorani have called home for centuries.

Despite a slick government sponsored campaign to promote investment, many oil blocks, including Block 22, were not successfully sold at auction. Oil investors cited “risks” associated with community opposition and unattractive financial terms.

However, for the Waorani the “failed” oil auction was a warning. And a call to organize.

▼ Here, Omene Iwa, from the community of Tzapino tells how his ancestors defended the land with spears. For Waorani elders, the current threats are too great to confront with spears alone, and so the youth must find new ways to defend their territory against unrelenting global pressures.

▼ In this photograph, youth leader Oswando Nenquimo reads a message to the Ecuadorian Government: “We do not recognize what the government calls Oil Block 22. Our forest homeland is not an oil block. It is our life.”

As a strategy of resistance, from 2015-2018, Waorani youth and elders set out to document and demonstrate life in their territory by creating a “living map” of their connection to the land, using GPS, film, camera traps, drones, and a customized mapping program that allowed them to work offline in remote forest.

Whereas the maps of oil companies only show petroleum deposits and major rivers, the maps that the Waorani created tell the story of their people’s relationship with the plants, the trees, the water, and the animals.

▼ Their maps identify historic battle sites, ancient cave-carvings, jaguar trails, medicinal plants, animal reproductive zones, important fishing holes, creek-crossings, and sacred waterfalls.

▼ In this photograph, school kids in the village of Nemonpare display their drawings of what they like most about life in the forest.

In 2018, the Ecuadorian Government announced renewed plans to auction million of acres of the southcentral Amazon to the oil industry.

▼ Here is a map illustrating the 16 proposed oil concessions, and their overlap with the ancestral territories of 7 indigenous nations.

“Oil Block 22” was once again up for sale to the highest petrol company bidder.

In a series of urgent region-wide assemblies the Waorani decided to take legal action to halt the sale of their lands.

▼ In a public hearing in the village of Nemonpare, the Ecuadorian Human Rights Ombudsman takes testimony from youth and elders in preparation for the lawsuit.

Dozens of hours of interviews revealed that the government’s “consultation process” relied on time-tested tactics of manipulation and deceit, and was designed to keep Waorani villagers in the dark about the potential impacts of oil operations in their territories.

“The government came to our village for an hour and promised us hospitals and schools. We didn’t know that they were planning on selling our land to the oil companies.” − Wina Boyotai from Kiwaro ▼

“For the government, the sale of our land was a foregone conclusion. They had already drawn up the plans and the maps. They didn’t come to consult us. They came to trick our people into signing a piece of paper. But we know we have rights, and we are ready to defend them.” − Oswando Nenquimo from Nemonpare ▼

▼ Here, in the community of Nemonpare along the Curaray river, villagers prepare banners to take to the city to defend their rights and make their voices heard.

Victory for the Waorani

▼ On February 27, 2019, hundreds of Waorani villagers from “Oil Block 22” marched to the courthouse in the Amazonian frontier town of Puyo to file their landmark lawsuit against the Ecuadorian government.

▼ In these photographs, Waorani women lead the march to the courthouse.

Many indigenous peoples from across the Amazon traveled to support the Waorani peoples’ historic fight to protect their lands from oil drilling. ▼

▼ In this picture, Nemonte Nenquimo, President of the Waorani Organization of Pastaza, carries the lawsuit in her hands, as Amazon Frontlines lawyer, Maria Espinosa addresses a crowd of supporters.

▼ In the courthouse building, the lead plaintiffs wait to file their landmark lawsuit. From left to right, Memo, Omanka, Nemonte, Wina, and Dika.

▼ In these photographs, the Waorani enter the courtroom to face off with the Ministry of Hydrocarbons, the Ministry of Non-Renewable Resources, and the Ministry of the Environment. Photography was not permitted during the court proceedings.

▼ On April 26th, just hours before the landmark verdict in the Waorani trial was announced, Nemonte Nenquimo addresses a crowd of supporters and media on the front steps of the courthouse. “No matter what the court says today we will not let oil in our lands. Our land is not for sale!”

THE VERDICT IS IN! VICTORY FOR THE WAORANI PEOPLE!

▼ Here Nemonte Nenquimo shares details of the historic verdict at a press conference outside the courthouse. The three-judge panel ruled that the Ecuadorian government had violated the Waorani’s rights to prior consultation and self-determination.

▼ In these photographs, the Waorani joyously march through the streets of the Amazonian town of Puyo during a torrential downpour. The court’s ruling immediately halts the government’s plans to sell their land to the oil industry, and sets a precedent for other indigenous nations to do the same.

Back to the Forest

After the historic court ruling which protects a half-million acres of their ancestral land from oil drilling, the Waorani returned to their forest homes.

And drank from the freshwater creeks.

And enjoyed the beauty of the waterfalls.

And walked freely in their forest.

The Waorani’s landmark legal victory protects their ancestral homeland from oil and sets a powerful precedent for other indigenous nations to do the same, but this watershed moment could be snatched away in the next two months by a legal appeal. The Ecuadorian judicial system is not immune to political influence, especially with millions of acres of “untapped oil reserves” at stake and the Government’s keen interest in undoing this powerful legal precedent for indigenous rights.

We must seize the momentum, and turn national and global attention into an even bigger victory for indigenous peoples, the Amazon and our climate.

Here’s what you can do today:

Keep The Oil In The Ground: Waorani Take Ecuador’s Government To Court This Thursday

One of the most biodiverse places on earth – in the heart of the Ecuadorian Amazon rainforest – is under imminent threat from oil drilling. This is the home of the indigenous Waorani people of the Pastaza province, who have protected their ancestral forest lands for thousands of years – and now, they’re ramping up the struggle. On April 11th in the city of Puyo, Ecuador, the Waorani people will be taking the Ecuadorian government to trial alleging numerous human rights violations in the government’s efforts to earmark their lands for oil extraction.

This is a critical moment to build global awareness about the Waorani’s fight to protect their territory, strengthen indigenous land rights, and halt global climate change. Please watch and share this video to support the Waorani in their struggle, and to show the Ecuadorian government and court system that the world is watching to ensure the integrity of the judicial process!

The Waorani people’s efforts to protect their ancestral territory from oil extraction – nearly 500,000 acres of highly biodiverse, primary rainforest – has emerged as a flashpoint in the South American country, highlighting the stark gap between the Ecuadorian government’s thirst for oil revenues to relieve international debt and indigenous peoples’ internationally recognized rights to free, prior and informed consent, self-determination, collective territory and the rights of nature.

This Thursday, the Waorani will be mobilizing in the city of Puyo, bringing hundreds of leaders, warriors, fisherman, medicine people, elders and youth from deep in their forest territory to the courthouse. Donate now to help fund their logistics (transport, lodging, food). Every dollar will go directly to on-the-ground organizing costs.

Amidst the backdrop of decades of contamination and cultural disruption in indigenous territories across the Amazon by oil operations, the Waorani’s lawsuit aims to protect their homeland, one of the last bastions of wild-standing forest, from a similar fate. Alongside their legal action, the Waorani are using high-tech maps, global campaign strategies and multi-nation organizing to spearhead a resistance movement opposing fossil fuel extraction and to galvanize the protection of nearly 7 million acres of indigenous territory – a critical stronghold in the battle against climate change.

Amazon Frontlines will be standing with our indigenous Waorani partners on the ground as they take on the Ecuadorian government to demand respect for their rights, and to protect a forest which gives life to us all. Please stand in solidarity by reading and signing the Waorani’s petition, which they will be handing into the government in the coming months.

“Water Unites Us”: Building Solutions On The Frontlines Of Oil Extraction In the Amazon

By Kofan leader Emergildo Criollo, founding member of our indigenous partner organization, Ceibo Alliance.

Water is life. On a day of such great importance like World Water Day, and every day – we should be conscious of the health of our rivers, and our duty to care for them and not contaminate them, and advance solutions to protect them.

Water isn’t just for us humans – it’s for all animals, it’s for the fish we eat, and it’s for our entire planet. In our indigenous cosmovisions and cultures, water is a living being, just like us. We are connected to the rivers. There are also many beings and spirits that live in the river, and, like us, they can die from contamination.

Can you imagine not having clean water to drink or to give to your children? In 1973, the oil company then known as Texaco (now Chevron) arrived to the Ecuadorian Amazon. Before the company’s arrival, we lived well and our forest was free from contamination. But then the oil spills began and our communities became sick with diseases previously unknown to us. We later discovered that these diseases were impacts from the oil contamination. Our communities did not know this, and so we continued to drink water from the rivers that were full of oil. Many people died from sickness– including children.

Water United Us

Seven years ago, as indigenous nations affected by oil contamination, we realized that we were all facing the same threats and living with the same health crisis. We decided to take action in our communities and to seek solutions to these problems. We could no longer wait for a response from the State or the companies responsible. We began building rainwater catchment systems for families of the Kofán, Siona, Secoya and Waorani communities affected by contamination across the region. This project, known as ClearWater, really catalyzed this unity between our peoples, and it began with water. From this project, from this understanding that we must build our own solutions and that we will only achieve this by working together, Ceibo Alliance was born.

Now that we have clean water, we are stronger. Our resistance has grown. Our health has improved. We have already achieved so much together and we know we have the strength to make real change, and to fight against the threats our peoples face. If we don’t defend our territory, the rivers will continue to be more and more contaminated.

Having access to clean water in our communities has also helped us to keep our traditions strong, and strengthened us culturally, socially, and spiritually. Some of our communities drink yoko in the morning, others prepare chicha during the day – we can now prepare these drinks knowing that the water won’t make us sick. It has given us peace of mind to continue living and being who we are.

Our Vision for a Healthy Future

We have now built rainwater catchment systems for more than 1,000 families in 78 communities, but there are still families without access to clean water. Our goal is to reach every family.

Our vision is for the long-term sustainability of our work. This year, we’ll be going back out into the communities where we’ve installed the systems, carrying out maintenance and repair work, installing systems for new families, and working with community members to care for and take ownership of the project so that their children will continue to have clean water for the decades to come.

None of this would have been possible without the committed support of our international partners. From the beginning, Saving an Angel and Rainforest Foundation saw the importance of this work and helped us turn our dream into a reality have been there with us every step of the way, and they continue to support our work.

Protecting Water for Our Planet

We know that we’re not just fighting for our peoples, but for the whole world. Rainforests produce so much of our planet’s water through rain. If we don’t care for our forests, if the trees continue to be cut down and the rivers polluted, the world won’t have enough water and climate change will continue to accelerate. There is already less and less water available because of deforestation.

As extractive companies push further into the forest, we must be united in resistance. We must say no to extractive companies, we must not let them enter and destroy our territories. If we continue to stand strong, together, we can stop them and protect our rivers and our forests, for the future generations, and for the entire world.

Join our movement for clean water and for a healthy future in the Amazon:

“Without Unity, There Can Be No Triumph”: An Indigenous Voice on a Historic Victory Against Gold Mining In The Amazon

On this Day of International Human Rights, Alex Lucitante, a young indigenous leader from the Kofan people, shares his experiences from the frontlines of a historic victory against gold mining in ancestral Kofan territory. From reviving ancient yagé ceremonies (also known as ayahuasca) to strengthen community resistance to using technology in the defense of their land, the small community of Sinangoe’s path to victory and their struggle ahead is one marked by a fusion of innovation and ancestry – and above all, unified determination to protect their rainforest home from extractivism.

When Sinangoe’s victory happened on October 22nd 2018, I cried and felt so much emotion. It took a lot of sacrifice to get to that victory, which nullified 52 mining concessions on our ancestral territory that had been granted by the government in violation of our right to consent.

The community’s dream was what sparked this fight. Our territory gives us everything we need: it is our pharmacy, our supermarket. There lies our history, our roots, and the life that enables us to live in harmony. That is why it is so important for us to protect it, it is our home.

Mining threatened our territory. It threatened the river and the spiritual places which give us life and which teach us respect for life. For the Kofan people, the river is not just water and stones. To see a fish is to see food, and to see water is to see life in the river. If the rivers are contaminated, what will happen? In the spiritual world, when the spirits of the jungle leave us, everything else we have also gets lost. The community will no longer bother taking care of the river, because it won’t make sense. They will start working and buying things that are not from the territory, they will begin to dream with money and they will begin to destroy the territory.

“Mining threatened our territory, our rivers and the spiritual places which give us life”

Our ancestors taught us to fight with truth and respect. That helped us so much on this path. Beyond our spears, our crafts, our way of life, our language – yagé, or ayahuasca, is a deep part of our identity as Kofan. Sinangoe still does not appropriate what is proper to us. We were divided by the Evangelism or “civilization” which the Kukamas [outsiders] imposed upon us. They convinced our people that drinking yagé was diabolical. Our wisest elders were deceived and finally stopped drinking yagé.

So the youth of Sinangoe grew up without the knowledge of yagé – until this struggle began. With the community guard, we went to my father’s territory to drink yagé. We went to Siona territory, where some of the people have maintained the practice despite evangelization, and there we also drank yagé. From then onwards, some young people learned to prepare it and they now are drinking with the elders, ancestral wisdom-keepers. Then began the construction of the ceremonial house in Sinangoe earlier this year, when the community began the struggle in defense of its territory. First the struggle emerged and then the cultural recovery – and now all of this continues.

“Drinking yagé allowed for respect to grow amongst everyone, it strengthened our unity”

The main vehicle for this struggle was the unity of the community. That unity was built through hard work and difficult times because Sinangoe was previously divided by political issues, the personal interests of certain groups, and different ways of thinking. But it was not entirely divided: there was still this dream to remain united, to do something for the community and for the territory.

Drinking yagé made respect grow amongst everyone, it strengthened the unity. It made people understand that what is our is ours, and no one can take that away from us. Yagé helps you to understand your life but it is also makes you understand the life of the forest – when you hear its chants, its sounds, that is where there is life. You see mountains and you see that this is sacred land. It is where the spirit of the jaguar rests and wanders, and where the sound of the wind fuses to the forest, and this creates harmony so that everything can be well. We are not greater than the forest or our territories, we are equal, we are the same: this is the Kofan vision. And so through yagé, we become stronger on this path.

If we ask ourselves why Kofan territories or indigenous territories have been kept intact until today, and why they contain more land and biodiversity than anywhere else, it is because our ancestors cared for and defended our territories. The current community guard of Sinangoe is nothing new – it is something that has been a fact since the existence of the Kofan people; our ancestors were these guards.

But during this process of struggle, in exercise of our right to autonomy and self-governance, we saw the need to formalize this guard on paper and create a law prohibiting activities that certain groups, companies or people were doing in disrespect of the community. The community’s voice was not being heard and the State was not guaranteeing our rights. For example, there were people putting shotgun traps to hunt animals in order to sell them, throwing dynamite, poison and all kinds of chemical substances into the rivers, dredging the territory and destroying mountains… So our ancestors’ mandate applied, to defend our ancestral territory through the means of a guard, by means of our warriors.

“The State must guarantee our rights to our territories”

Technology, paired with the guard’s ancestral knowledge of our territory and how to navigate the river and adapt ourselves in the jungle, was very important in the Sinangoe case. The camera traps and drones served to document and monitor what was happening in the territory. At first, there were threats towards our leaders – “if we see you Kofan here, we will take out our machetes, we will cut off your head” – that is how the miners threatened us. But with all the photographic evidence which Sinangoe collected through camera traps and drones, we were able to file a demand for an action of protection. The denouncement was made public before the authorities, and through the media we alerted the world about the changes that were happening in our territory, about the illegal invasions but also about the mining concessions granted by the Ecuadorian government without our consent. When this happened, investigations were opened, and from then those who threatened us remained silent.

A few weeks ago, we met with the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Indigenous Rights during her visit to Ecuador. We explained how the State was not recognizing our rights to our territories as Kofan people, the State was violating our rights. We need the State to guarantee our rights through land titling. We also demanded that the State recognize the role of indigenous guards as guardians of ancestral territories and for the protection of the rainforest and biodiversity, because to this day, the State has been incapable of doing so. Instead, the State has accused us of being “paramilitaries”, “militia groups”, “accomplices of the miners”. But the Rapporteur met the guard to understand its structure and how it protects our territories: with respect, strength, and love in the heart.

Now the community is beginning a process to map out its territory, they will be walking long distances to gather evidence of sites of great importance in order to demand that the State recognize their territory through a property title. The State wants to have authority over these territories but they must respect our ancestry. With the case’s sentence and all the support and alliances that Sinangoe now has, we are confident that we will be able to secure this land title. And when we secure this land title, we will be stronger in our fight to guarantee our cultural and physical survival.

The struggle of Sinangoe doesn’t just represent the Ecuadorian Amazon. It also speaks to other countries – where indigenous peoples want to fight and confront these big issues but still feel lost because they do not really understand who they are as a people. In reality, we, indigenous peoples are subject to rights just like nature, so we must fight and defend who we are. When there is consciousness, as there is in the case of Sinangoe, people view who they are with pride and love. We raise our spears and say we are Kofan, and so what? It does not matter that we do not have the dream of the white man or of the extractivist to own a lot. We have the dream of our ancestors, which is the ancestral right to be who we are and live as we want to live. That is the message from Sinangoe to the world: get up, raise your voice, but always be united. Without unity, there will be no triumph.

List of chronicles in our series on Sinangoe:

Nothing found.

Stopping a gold rush in the Amazon: 7 reasons why the Kofan landmark victory is so huge

Facing the mounting pressures of the global race for gold and other metals across the globe, it’s not everyday that a small indigenous community wins a lawsuit against the government that nullifies over 50 mining concessions threatening their health and land, and grants full restoration of the damages done. Last week’s landmark victory for the Kofan people of Sinangoe, at the headwaters of the Aguarico River in the Ecuadorian Amazon, is testament to the importance of indigenous-led resistance against extractivism in the world’s largest tropical rainforest.

This community’s path to victory involved a myriad of strategies ranging from environmental monitoring to innovative legal actions and alliance-building with civil society, provincial governments and international organizations. Its example should provide inspiration and tools to other indigenous peoples facing similar threats to their ancestral lands, cultures and rights. Here are 7 major reasons why Sinangoe’s case is so important.

1. It safeguards the ancestral Kofan way of life

Kofan culture is deeply connected to the land: their entire way of life depends upon the rivers and forest. When the Kofan discovered that their ancestral territory along the Cofanes and upper Aguarico rivers had been granted to mining companies without their permission, they immediately recognized the gravity of this threat to their way of life and autonomy, and to other communities downriver. Damage to these rivers means damage to the Kofan themselves. Their triumphant legal battle, which brought four Ecuadorian State authorities to court, not only denounced the lack of consultation, but also highlighted the violation of their rights to water, food security and a clean environment – fundamental rights imperative to the integrity and survival of Kofan culture.

The Kofan people of Sinangoe have won a landmark legal battle to protect the headwaters of the Aguarico River, strengthening collective rights to Free, Prior and Informed Consent over any extractive activity in indigenous lands.

2. It shows the effectiveness of indigenous-led environmental monitoring

It was Sinangoe’s community land patrol that sounded the alarm when they witnessed the first machines digging up the banks of the Aguarico River in early 2018. This land patrol, trained and formed one year before in partnership with Amazon Frontlines and our indigenous partners Ceibo Alliance, immediately documented and reported the invasion. Over the course of several field trips, the land patrol meticulously built up an extensive archive of images, drone footage and maps, which played a central role in their landmark victory, providing irrefutable evidence of the environmental damages of gold mining on their land to the judges and court. This victory should embolden any community using environmental monitoring techniques, whether it be camera traps, GPS, video recorders, drone, satellite imagery and/or land patrols.

Over the course of 2 years, Sinangoe’s land patrol have used a wide range of strategies and technologies to detect, document and stop gold mining inside and around their ancestral land.

3. It sets a legal precedent for indigenous rights in Ecuador and beyond

The decision by the Provincial Court is without precedent in Ecuador, and takes huge steps towards the protection of indigenous and environmental rights. First, there is the concrete: 20 concessions improperly granted to mining companies canceled; 32 concessions under review for approval indefinitely suspended; and full remediation of damages already caused by the mining activity. But this sentence has deeper repercussions for a country with 14 indigenous nations and some of the world’s most important natural resources. The court’s recognition that the government must consult indigenous communities when the proposed activity affects their territory, even if it doesn’t occur directly on their legally recognized land, is a huge win for indigenous rights to Free, Prior and Informed Consent. Equally important is the recognition of the rights of nature, as well as the use of the precautionary principle, always applicable but seldom-applied in Ecuador, which vests the government with the responsibility to protect the public from harm (in this case to the environment and to the right to water and food security) BEFORE irreversible damage occurs unless scientific evidence can prove otherwise. The court’s decision advances the law in Ecuador, paving the way for other communities to exercise their rights and protect their territories.

4. It protects one of the most biodiverse places on Earth from rampant deforestation

By halting all mining operations along the headwaters of one of Ecuador’s most important rivers, the Kofan have saved 32,000 hectares (79 000 acres) of the most biodiverse rainforest in the country and amongst the most biologically rich places on Earth. The area, fed by the Cofanes and Chingual Rivers, is home to over 3,725 species of plants, 650 species of birds and 50 species of mammals, including various endemic and endangered species like the spectacled bear and the mountain tapir. This biological hotspot’s fragility and uniqueness mean even limited road building and small-scale deforestation could have disastrous impacts on the local flora and fauna. This legal victory affords respite for these wild places and highlights the incompatibility of mining in this pristine Amazon rainforest.

5. It contributes to the fight against the global climate crisis

As deforestation continues to spread across the Amazon, and with the Ecuadorian Amazon having already lost 675,000 hectares of pristine rainforest since 1990, protecting intact refuges like Sinangoe’s ancestral land and its rich surroundings is key to combating climate change. Each hectare of forest in this area contains between 245 to 633 tons of carbon stored in its vegetation and soils, amongst the highest carbon densities in the Amazon1. Avoiding deforestation over 32,000 hectares of this rainforest means avoiding the release of at least 7.8 million tons of carbon to the atmosphere, or the equivalent average yearly carbon emissions of more than 1.7 million cars2.

Deforestation along the banks of the Aguarico River detected by Sinangoe’s land patrol in April 2018.