COVID-19, A Stern Warning From Nature

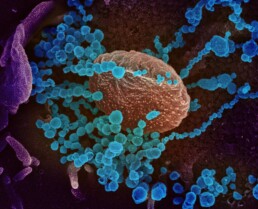

This chronicle follows the causal arc from biodiversity loss through to increasing pandemics, putting at risk the most vulnerable sectors of society, including the very indigenous people who are some of the best custodians of biodiversity. We review evidence of the links between the destruction of the environment and disease emergence and expand the discussion to cover the potential for epidemics to arise in the Amazon.

Forlorn Warning

Researchers looking at the links between the health of ecosystems, animals and humans have foretold of a pandemic for years (Fan et al. 2019). The who, what, where and when of the current, surreal drama in which we have all unwittingly become pivotal characters in central casting were a mystery. But the stage was set on the ‘how’ decades ago.

The alarm raised by scientists mostly fell on deaf ears, until crisis hit.

The story begins with human encroachment into natural landscapes. Across the world, industrial activities such as agriculture, ranching, hydroelectric dam construction, urbanization, logging, oil extraction and mining are replacing earth’s original biomes with ones in which humans dominate. 76% of the earth’s land has already been altered, leaving only 23% to wilderness (Watson et al. 2018). This is the setting…

…now, the scenario. Land degradation provokes biodiversity loss, which in turn facilitates the propagation of diseases. Here is how it plays out. Diverse ecosystems harbor high biodiversity with significant genetic diversity. The genetic diversity of potential victims hampers the spread of disease by consistently posing unique challenges to would-be-killers (van Houte et al., 2016). If the genetic diversity of the potential target animal is high it will be harder to find a foolproof way to circumvent the immune system designed to thwart it and sneak past the cellular wall. On the other hand, if the gene pool is low, as it is when animal biodiversity is lost, pathogens quickly find solutions to dupe hosts’ immune systems and then spread rapidly throughout the relatively uniform population.

Enter HUMANS. Meanwhile, landscapes where humans dominate lead to a greater proportion of species that can tolerate the presence of humans, such as rodents and bats, as the more reclusive types slink deeper and deeper into the remaining wilderness. Exit more BIODIVERSITY. Furthermore, some of the characteristics that make these species adaptable to human environments also make them excellent hosts for infectious diseases: high mobility, longevity, and social living in colonies (Mühldorfer, 2013). As demonstrated by indigenous people across the globe, we do have the capacity to occupy spaces without dominating and degrading them: 80% of the world’s biodiversity resides inside traditional indigenous territories (Sobrevilia, 2008). But when human activities run amok and push really comes to shove, it’s Mother Nature who has the last words: Back off!

‘Whodunit’

Here’s where the plot thickens. As humans inhabit these shifting landscapes containing less and less biodiversity they come into contact with unforeseen pathogen hosts. The most common suspects are either domesticated animals or those sociable, adaptable, human tolerant characters, the rodents and bats. Original hosts develop immunity to pathogens over eons, carrying them unknowingly. Spillover events – when a pathogen adapts to use a new host – sometimes lead to permanent host shifts and are common in evolutionary history (Longdon et al. 2014). This is the making of an epidemic, because the new host has no immunity to the “novel” virus.

Coronaviruses, which are a large class of viruses normally found in rodents, bats and birds, cannot directly affect humans, and must pass through an intermediary host first. In a foreshadowing of what is coming to pass with COVID-19, SARS took center stage in 2002 when this coronavirus moved from bat to civet, a small nocturnal mammal, before becoming virulent for humans. Avian and swine flu often originate in domesticated animals. The H1N1 epidemic of 2009 has been traced to central Mexico and is believed to be the result of long-distance live pig travel allowing several strains of virus to recombine, generating a bug that could inflict harm on humans (Mena et al. 2016).

The “Spanish” flu of 1918 infected 500 million and killed between 50 and 100 million people (Sutton, 2018). The origins of this H1N1 virus are murky, but there was certainly a crossover from birds to humans, likely involving pigs as intermediary hosts (van Wijhe et al. 2018). Interestingly, it is believed that this virus was able to attain pandemic proportions despite the simplified demographics of the time due to troop movements throughout Europe and back to North America during WWI (van Wijhe et al. 2018). Few places escaped the pandemic, which reached its tendrils into the remotest regions of the world, including the Amazon (Chowell et al. 2011).

Scientists are furiously investigating how the SARS-CoV-2 virus jumped the species barrier to arrive in humans causing COVID-19. Inquiries have revealed that the original host is most certainly a bat. Molecular studies are pointing to the intermediary host being either pangolin – an endangered mammal traded illegally in wet markets of Asia – snakes or turtles, which are both legally sold at market (Liu, et al. 2020). This fact points to the primacy of clamping down on the illegal trade of wildlife and tightening up laws where they are lax, especially with respect to the sale of live animals at ‘wet’ markets.

Albeit on a lesser scale than in Asia, wet markets abound in urban centers around the Amazon (pictured above, the Belén market in the city of Iquitos, Peruvian Amazon). There, you can purchase a vast array of bush meat and exotic animals for pets. Live markets are ideal venues for humans to come into contact with potential pathogen hosts

| 1918 flu | SARS | H1N1 | MERS | COVID-19 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| “Who” | Bird->(swine?)->human | Bat->civit->human | pig->human | Bat->camel->human | Bat->?->human |

| What | Swine flu | Coronavirus | Swine flu | Coronavirus | Coronavirus |

| Where | Europe->US (?) | China | Mexico | Middle east | China |

| When | 1918 | 2002-3 | 2009 | 2012 | 2019 |

It would be all too easy to point the finger at the bat or the ‘Chinese’ in this modern-day mystery, but the real culprit is human greed and its accomplice, rampant resource extraction. Since the COVID-19 outbreak, news outlets have published countless articles describing the settings in which pandemics arise and the UN’s environment chief, Inger Andersen has emphasized that “our long-term response must tackle habitat and biodiversity loss”. Hopefully, central protagonists, such as researchers and health care professionals, can control the narrative keeping the focus on the underlying causes of the COVID-19 crisis, not easy ‘scapebats.’

Burning the Amazon: Igniting a future pandemic?

The 2019 dry season in the Amazon had the world on the edge of its seat as unfathomable acreage of pristine rainforest and previously cleared forest burned at the hands of land owners hungry for more land on which to grow cash crops, such as soy and cattle. All of this charred land is on the ancestral territories of the Amazon’s original people; however, it is unclear how much of the burned area was on land currently under indigenous jurisdiction. Contrary to elsewhere in the world, the main driver of land use change in Brazil is rising affluence, not poverty or population growth (Nava et al., 2017). In this sense, avarice is the principal motor of land clearing, while fire is the vehicle, setting in motion biodiversity loss and potentially providing the spark for a spillover event.

The vast majority of emerging zoonotic diseases in South America are vector-borne diseases, such as malaria, dengue, chikungunya, and zika, which require a vector, like a mosquito, to infect humans. COVID-19 is an ‘air-borne’ infectious disease. Vector-borne diseases are dependent on the ecological niche of the vector (temperature range, humidity, etc.) making it much less likely that they would reach pandemic scale; whereas airborne diseases travel easily from one human to the next in a wider range of habitats.

Hantaviruses, common in South America, are airborne viruses of bat origin which are known to occasionally spillover into rodents. In humans, they cause different ailments including hantavirus cardiopulmonary syndrome (HCPS). Hantavirus infections increased 800% in Brazil between 2001 and 2009 (Laerte Pinto, et al. 2014). As opposed to coronavirus, very little human-to-human transmission of hantavirus has been observed, but the few cases in which it did arise in Argentina demonstrate that it is possible.

Research along the deforestation arc of Brazil, the world’s largest deforestation frontier, has demonstrated that bat diversity is significantly lower than in the rest of the Amazon. Two species, the greater spear-nosed bat, Phyllostomus hastatus, and the gnome fruit-eating bat, Dermanura gnoma, were found to have antibodies signaling that they are hantavirus carriers (Sabino-Santos Jr, et al. 2019).

Fires further aggravate the problem because as fields and forests are lit, rodents flee flames taking shelter in dwellings, where humans come into direct contact with them (Laerte Pinto et al. 2014). Bats are also disturbed by fires. Prior to the deadly Nipah outbreak in Asia in 1997-1998, smoke from severe forest fires drove fruit eating bats from the forest into orchards, where a novel virus was forged upon recombination with pig viruses (Bonilla-Aldana et al. 2019). Climate change also contributes to diminishing biodiversity: projections show that, as it heats up and dries out, large swaths of the Amazon could shift to savannah-type landscapes, which house considerably less wildlife than tropical rainforests.

Furthermore, very preliminary data coming out of Italy is leading some scientists to believe that air pollution acts as a carrier for COVID-19. Viruses hitchhike on the particles in the air, facilitating its spread. Previous research has shown that dust storms (Chen et al., 2010) and haze (Ye et al., 2016) act as propagation mechanisms for other respiratory illnesses. If this is the case, COVID-19 or a potential hantavirus outbreak could be widely broadcast by the next Amazon fire season. The lower fauna richness in general, proliferation of human tolerant animals and proximity with settlers following deforestation through burning, would constitute significant risk factors for possible disease emergence in the Amazon. And indigenous people, who are in the firing line between settlers and the falling forest, could be the first to fall victim to an Amazonian virus making its debut.

Several recent deaths in Ecuadorian indigenous Shuar and Siekopai communities are suspected to be COVID-19 related, while in Brazil, there have been at least three COVID-19 deaths and 27 confirmed cases among indigenous people to date.

The specter of new pandemics adds one more motive in our arsenal of reasons to conserve intact forests. One way of doing this is to slow down resource extraction and agricultural expansion in a post COVID-19 era. Already, indigenous peoples in the Amazon have been demanding an immediate moratorium on any activity that includes the entrance of foreigners into indigenous territories, mining activities, logging, oil exploration and extraction, industrial agriculture, religious proselytization, or increased militarization, especially in trans-border territories under pressure from armed actors and organized crime.

Unfortunately, in some places companies and desperados are taking advantage of the dire situation to push ahead with controversial activities including mining. Meanwhile, in the Brazilian Amazon, indigenous people have witnessed an increase in illegal activities and reduced law enforcement. This lapse in vigilance could exacerbate the 2020 fire season, and as we have seen, fires in the Amazon pose a particularly volatile situation in which diseases could emerge and propagate rampantly among some of the world’s most vulnerable people. However, the COVID-19 crisis has, in other instances, temporarily paused many of these industrial activities, fugitives on the lam, and, in some places, encouraging signs of cleaner air and animals repossessing key habitats are emerging. These beacons show us that another world is possible. Indigenous land management practices are another lodestar: 40% of the world’s protected and natural spaces overlap with indigenous lands (Garnett et al. 2018), highlighting that their management strategies simultaneously allowed for their own survival and the survival or abundant biodiversity.

We still have time to contain the impact of COVID-19 on indigenous communities and avoid a catastrophic loss of life. Please donate to the Amazon Emergency Action Fund to help indigenous communities get information, supplies and medical services to protect themselves during this crisis.

Reference.

Bonilla-Aldana, D. K., J. A. Suárez, C. Franco-Paredes, S. Vilcarromero, S. Mattar, J. E. Gómez-Marín, W. E. Villamil-Gómez, J. Ruíz-Sáenz, J. A. Cardona-Ospina, S. E. Idarraga-Bedoya, J. J. García-Bustos, E. V. Jimenez-Posada and A. J. Rodríguez-Morales (2019). “Brazil burning! What is the potential impact of the Amazon wildfires on vector-borne and zoonotic emerging diseases? – A statement from an international experts meeting.” Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease 31: 101474.

Chen, P.-S., F. T. Tsai, C. K. Lin, C.-Y. Yang, C.-C. Chan, C.-Y. Young and C.-H. Lee (2010). “Ambient Influenza and Avian Influenza Virus during Dust Storm Days and Background Days.” Environmental Health Perspectives 118(9): 1211-1216.

Chowell, G., C. Viboud, L. Simonsen, M. A. Miller, J. Hurtado, G. Soto, R. Vargas, M. A. Guzman, M. Ulloa and C. V. Munayco (2011). “The 1918-1920 influenza pandemic in Peru.” Vaccine 29 Suppl 2(Suppl 2): B21-B26.

Garnett, S. T., N. D. Burgess, J. E. Fa, Á. Fernández-Llamazares, Z. Molnár, C. J. Robinson, J. E. M. Watson, K. K. Zander, B. Austin, E. S. Brondizio, N. F. Collier, T. Duncan, E. Ellis, H. Geyle, M. V. Jackson, H. Jonas, P. Malmer, B. McGowan, A. Sivongxay and I. Leiper (2018). “A spatial overview of the global importance of Indigenous lands for conservation.” Nature Sustainability 1(7): 369-374.

Fan, Y., K. Zhao, Z.-L. Shi and P. Zhou (2019). “Bat Coronaviruses in China.” Viruses 11(3).

Mühldorfer, K. (2013). “Bats and Bacterial Pathogens: A Review.” Zoonoses and Public Health 60(1): 93-103.

Laerte Pinto, V. J., H. Amani Moura, F. Dalcy de Oliveira Albuquerque and S. Vitorino Modesto dos (2014). “Twenty years of hantavirus pulmonary syndrome in Brazil: a review of epidemiological and clinical aspects.” The Journal of Infection in Developing Countries 8(02).

Liu, Z., X. Xiao, X. Wei, J. Li, J. Yang, H. Tan, J. Zhu, Q. Zhang, J. Wu and L. Liu (2020). “Composition and divergence of coronavirus spike proteins and host ACE2 receptors predict potential intermediate hosts of SARS-CoV-2.” Journal of Medical Virology n/a(n/a).

Longdon, B., M. A. Brockhurst, C. A. Russell, J. J. Welch and F. M. Jiggins (2014). “The evolution and genetics of virus host shifts.” PLoS pathogens 10(11): e1004395-e1004395.

Nava, A., J. S. Shimabukuro, A. A. Chmura and S. L. B. Luz (2017). “The Impact of Global Environmental Changes on Infectious Disease Emergence with a Focus on Risks for Brazil.” ILAR Journal 58(3): 393-400.

Mena, I., M. I. Nelson, F. Quezada-Monroy, J. Dutta, R. Cortes-Fernández, J. H. Lara-Puente, F. Castro-Peralta, L. F. Cunha, N. S. Trovão, B. Lozano-Dubernard, A. Rambaut, H. van Bakel and A. García-Sastre (2016). “Origins of the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic in swine in Mexico.” eLife 5: e16777.

Sabino-Santos Jr, G., F. F. Ferreira, D. J. F. da Silva, D. M. Machado, S. G. da Silva, C. S. São Bernardo, M. dos Santos Filho, T. Levi, L. T. M. Figueiredo, C. A. Peres, R. V. de Morais Bronzoni and G. R. Canale (2019). “Hantavirus antibodies among phyllostomid bats from the arc of deforestation in Southern Amazonia, Brazil.” Transboundary and Emerging Diseases: 1– 7.

Schneider, M. C., P. C. Romijn, W. Uieda, H. Tamayo, D. F. d. Silva, A. Belotto, J. B. d. Silva and L. F. Leanes (2009). “Rabies transmitted by vampire bats to humans: an emerging zoonotic disease in Latin America?” Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública 25(3): 260-269.

Sobrevila, C. (2008). The Role of Indigenous Peoples in Biodiversity Conservation: The Natural but Often Forgotten Partners. Washington, D.C. , The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / THE WORLD BANK.

Sutton, T. C. (2018). “The Pandemic Threat of Emerging H5 and H7 Avian Influenza Viruses.” Viruses 10(9): 461.

van Houte, S., A. K. E. Ekroth, J. M. Broniewski, H. Chabas, B. Ashby, J. Bondy-Denomy, S. Gandon, M. Boots, S. Paterson, A. Buckling and E. R. Westra (2016). “The diversity-generating benefits of a prokaryotic adaptive immune system.” Nature 532(7599): 385-388.

van Wijhe, M., M. M. Ingholt, V. Andreasen and L. Simonsen (2018). “Loose Ends in the Epidemiology of the 1918 Pandemic: Explaining the Extreme Mortality Risk in Young Adults.” American Journal of Epidemiology 187(12): 2503-2510.

Watson, J. E. M., O. Venter, J. Lee, K. R. Jones, J. G. Robinson, H. P. Possingham and J. R. Allan (2018). “Protect the last of the wild: Global conservation policy must stop the disappearance of Earth’s few intact.” Nature 563: 27-30.

Ye, Q., J.-f. Fu, J.-h. Mao and S.-q. Shang (2016). “Haze is a risk factor contributing to the rapid spread of respiratory syncytial virus in children.” Environmental Science and Pollution Research 23(20): 20178-20185.

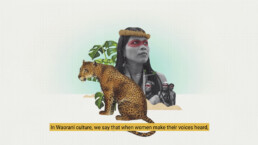

"Are You A Good Ancestor?”: A Message From Indigenous Leader Nemonte Nenquimo For Earth Day

“Are you a good ancestor?” This Earth Week, Waorani leader Nemonte Nenquimo from the Ecuadorian Amazon calls upon us to become guardians of nature for our planet and future generations. Nearly one year ago – on Sunday 26th April – Nenquimo helped to lead her people’s historic victory against Big Oil protecting a half million acres of primary rainforest in the Amazon, galvanizing indigenous movements’ efforts to halt the expanse of natural resource extraction across approximately seven million acres of mega-biodiverse rainforest.

This powerful animated short, created in collaboration with our allies Global Wildlife Conservation, is the third in their five-day series entitled “One Home”, celebrating the interconnectedness of all life on the planet for the 50th anniversary of Earth Day. In the midst of a global pandemic, Nenquimo continues to raise her voice to urge us to protect our world’s last wild places. An overwhelming body of scientific evidence has demonstrated what indigenous peoples already knew for thousands of years: healthy forests are vital for the health of our planet, and our shared existence and climate.

Tragically, indigenous peoples, who are on the frontlines of the battle to protect the Amazon, our world’s most important rainforest, fear ethnocide should the foreign disease cause a widespread outbreak in their territories. Nenquimo is one of the many leaders helping to organize indigenous communities’ response efforts to protect themselves from the highly contagious virus, which has devastated Ecuador. Numbers suggest the South American country is suffering one of the worst outbreaks in the world. Several indigenous communities, including within the Siekopai and Shuar nations, have reported recent deaths, which are suspected to be COVID-19 related – but the lack of access to tests in the country has not allowed for these deaths to be confirmed.

To support indigenous-led actions and solutions to the pandemic, we launched an “Amazon Emergency Action Fund (COVID-19)” campaign earlier this month, in partnership with indigenous organizations of the Ecuadorian Amazon. There’s still much support needed – click here to make a donation.

Indigenous Knowledge Keeps Forests Standing

Indigenous peoples have been protecting the Amazon, our world’s largest rainforest, for thousands of years. Today, in the face of our climate crisis, biodiversity loss and a global pandemic, we celebrate the forests which give life to our world. It is thanks to indigenous peoples that our world’s last wild forests are still standing.

In these uncertain times, we stand strong with our indigenous partners in their struggle to continue defending the Amazon against all odds: their knowledge and wisdom is essential in paving a path forward towards a balanced planet and to restore harmony with the natural world. They know that our future is irreconcilably intertwined with the fate of the Amazon.

Watch and share this video on World Forests Day to show your support and help grow the movement!

The Water Protectors Of The Amazon

As our planet’s mightiest river, the Amazon and its tributaries form the most intricate and biodiverse water system in the world. Without it, we would lose over one fifth of our planet’s freshwater supplies and our largest rainforest – the lungs of the world – would cease to exist. In the face of escalating pressures and threats from the industrialized world, indigenous peoples are at the forefront of movements to protect water and the rivers that are the lifelines to their ancestral rainforest territories.

Rivers are essential for the daily life of thousands of indigenous communities across the region, and have sustained their cultures, their livelihoods, and ways of life for thousands of years. Yet the health of the Amazon’s rivers is increasingly at risk. Unprecedented rates of deforestation and the advance of the extractive frontier are pushing the Amazon rainforest towards a dangerous tipping point, which could be less than thirty years away. Scientists affirm that at the current rate of deforestation, the Amazon’s rainfall will soon be drastically reduced, drying up rivers and the rainforest, and dramatically altering our planet’s climate, health, and freshwater resources.

Indigenous peoples are on the frontlines taking action and building solutions to defend rivers and their biodiversity for their peoples and the planet. In the following photo-essay, we take a snapshot journey through the Amazon’s rivers, and into the lives and struggles of the Amazon’s indigenous water protectors who are winning remarkable victories for rivers and the rights of nature despite all the odds.

Indigenous cultures of the Amazon maintain a deep spiritual connection with rivers. According to their cosmovisions, water is a living being and spirit, and rivers are inhabited by many different beings and spirits, such as the powerful boa, which help to protect the harmony and balance of the Amazon.

The ancient plant medicine of Yagé (ayahuasca) is prepared by shamans using water collected from streams and creeks. Yagé has been traditionally consumed by indigenous peoples of the Amazon – some say for hundreds or even thousands of years – as a means to bring forth healing, wisdom, and guidance for their communities.

“When our rivers become contaminated, the spirits are affected just like we are. The spirits of the river and the forest leave us, and everything else we have – in our territory and as a people – gets lost.”

– Kofan leader Alex Lucitante

Indigenous people's fight for clean water

In Ecuador’s Amazon, oil company Texaco (now Chevron) began operations in the Amazon back in the 1960s and is responsible for one of the worst oil-related disasters in history, with catastrophic consequences for rivers and communities’ water sources in one of the most biodiverse places of our planet.

In the face of ongoing oil contamination, state abandon and impunity, indigenous communities of the Kofan, Siona, Siekopai and Waorani nations of the Ecuadorian Amazon unite to fight for clean water. Amazon Frontlines’ story and work, in partnership with our indigenous partner organization Ceibo Alliance, began here.

“These rainwater harvesting systems that will provide families with clean drinking water are the result of our hard work. We built these systems. We will take care of them. Together we can improve the quality of life for our own communities.”

– Kofan leader Emergildo Criollo

Major Victories For Rivers

In a powerful moment for the Rights Of Nature, the Kichwa people of Santa Clara won an important legal victory last year protecting one of the Ecuadorian Amazon’s most beautiful rivers, the Piatua and halting the construction of a hydroelectric dam which threatened not only the river but also the Kichwa people’s way of life.

The Kofan people of Sinangoe in Ecuador’s Amazon won a historic legal battle against the Ecuadorian government in 2018, blocking a gold rush on their ancestral rainforest territory and protecting the Aguarico river. The ruling sets an important precedent for indigenous rights across the Amazon, as well as an important step forward for the rights of nature.⠀

Indigenous unity across the Americas. Indigenous activist Eriel Deranger from the member of the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation in Canada, alongside Waorani leaders Nemonte Nenquimo and Silvana Nihua, visits ancestral Waorani territory a few months before the communities’ major legal victory against big oil

“We need to unite in the struggle because the fight is not only for indigenous people but for all of humanity. We have to sustain our planet. That is what we have to do: Unite to save our planet.”

– Waorani leader Nemonte Nenquimo

Letter from Indigenous Women of the Western Amazon

A Letter From Kofan, Siekopai, Siona, and Waorani women of our indigenous partner organization, Ceibo Alliance. Click here to read the original Spanish letter entitled “We Are Resistance of The Forest, Love & Peace”.

With love and peace, we, women from four indigenous nations of the Western Amazon, are fighting against the threats to our forest.

The Amazon gives life to our planet. And for us, as indigenous peoples, it is our home. Yet every day, the threats grow bigger. Oil companies, loggers, cattle ranchers, and armed groups endanger our lives and destroy our territories, and governments continue to violate our rights. They want to exploit our territories, displace us, and exterminate us. They do not want us to live in peace and harmony. They continue to contaminate our Mother Earth, our rivers, our animals, and our bodies. And as the forest is destroyed, our cultures and our ancestral knowledge are disappearing even faster – and forever.

As women, we were deeply saddened and pained to witness the fires that devastated millions of acres of primary rainforest in Brazil, Bolivia and Paraguay last year, as a result of the invasions of cattle ranchers and large agribusinesses on indigenous lands. Despite the distance between our homes, we know that we are all united in this fight to protect our forest. The Amazon is not divided in parts, it is one whole being. And we know that what happened with the fires could also happen here, if the trees continue to be cut down, and if extractive companies continue to enter our territories. Our forest could dry up and become a desert.

Building the Path Forward

Over the past few years, we have achieved great victories here in the Ecuadorian Amazon, which have strengthened us and given us hope in our fight against extractivism and for the cultural survival of our peoples. At the headwaters of the Aguarico River in the northern Ecuadorian Amazon, the Kofan community of Sinangoe won a landmark victory against gold mining and for the rights of nature. The courts recognized that the government had violated the Kofan’s right to prior consultation and that mining threatened their survival and the rivers. And more recently, Waorani communities from the south-central Ecuadorian Amazon won a historic battle against big oil. Women, grandmothers, and girls were at the forefront of these unprecedented legal victories, alongside men, demanding that the State respect indigenous peoples’ rights and decisions over their territories. And we triumphed!

But we know that the threats to our lives and our territories will not diminish. As women, we are growing stronger. We are standing up for our rights and putting our bodies on the line to defend our families and our territories. We are active in our communities’ land patrols (or “guardias”), climbing tremendous mountains, detecting new threats, confronting invaders, and protecting life. Women defenders are setting a courageous example for our girls and for the generations to come. They bravely take on this work, in addition to all the responsibilities they have as a woman in their community and in the face of ongoing gender discrimination. These women strengthen our fight for equality against a patriarchal system: because this fight includes everyone.

Weaving Our Dreams

We dream of a future where our grandchildren can enjoy the inheritance from their ancestors: a forest in which they can breathe fresh air, run freely, and lead a healthy life. Over the past years, we have been organizing ourselves and creating women’s associations to create economic alternatives to resource extraction for our families and communities, through initiatives such as tailoring, hand crafts, and other products such as chocolate.

We are now embarking on a powerful journey to build our own educational systems, based upon our cultures and ways of life. We believe that an education rooted in our identity and our territory will strengthen our struggle to defend the forest, and allow our grandchildren to grow strong and confident. They’ll be able to speak their own language, and carry on our traditions, our customs and our cosmovisions. They won’t be as vulnerable to discrimination and they’ll be able to interact with the Western world without the need to change their identity.

Women are guardians of the ancestral knowledge of our peoples. Women have always been important because we are the ones who take care of and raise our children. Our grandmothers are pillars for our communities. They have many stories to tell, much advice to offer, and lots of wisdom to share. For this reason, we also aspire to become journalists, photographers and filmmakers. We want all women’s voices to be heard. We want our stories to be told, our ancestral knowledge to be recovered, and our visions to be shared according to our own experiences and our strength as women.

We will continue dreaming to protect our forest. We are the earth, the water, the air. We are the forest itself. And for her, we will continue to fight and unite until the end, with lots of love, and lots of rebellion.

“Our Forest Is Our Life": Indigenous Peoples from Ecuadorian Amazon Defend Historic Victories For Indigenous Rights & Amazon Protection

After a long journey from the Amazon traveling by foot, by canoe and by road, hundreds of indigenous peoples arrived in Ecuador’s capital city last week to mobilize in support of the Waorani and Kofan nations, whose historic victories against oil and mining interests have inspired hundreds of indigenous communities across the Amazon in their resistance against extractivism.

United with other indigenous nations from the Ecuadorian Amazon including the Kichwa, Sapara, Shiwiar, Shuar, Siekopai, and Siona, who face similar rights violations and threats in their territories, indigenous youth and elders took to the streets of Quito in song and dance and staged powerful mobilizations outside several State institutions to denounce the government’s ongoing complicity in Amazon destruction and its failure to comply with their court rulings. The Waorani and Kofan notably met with Ecuador’s Supreme Court, which has accepted the Kofan of Sinangoe’s case for review – an important feat for indigenous peoples in Ecuador, which could also mark the country’s first ever Supreme Court ruling on prior consultation and the right to self-determination as applied to indigenous peoples.

The Waorani and Kofan know the stakes are high, and that their victories present invaluable opportunities to advance the law and indigenous rights not only in Ecuador, but across the region. Yet despite their important triumphs against big oil and mining and the recognition of the importance of their cases by Ecuador’s Supreme Court and the United Nations, the government’s extractive agenda continues full throttle. Recent announcements reveal plans to expand oil and mining concessions in the Amazon in order to repay the country’s crushing debt to China, imperiling our world’s most important forest, indigenous territories, and our planet’s climate.

In 2018 and 2019, the Kofan and Waorani won unprecedented legal battles against the Ecuadorian government, protecting hundreds of thousands of pristine megabiodiverse rainforest, and setting invaluable legal precedents for indigenous rights in the country and the Amazon region. In the months ahead, the Waorani and Kofan will continue to ramp up the pressure to ensure that the Ecuadorian government respects indigenous rights and territories.

“We are the voice of the forest. We demand that the government listen to us and respect us. We continue to resist. Our legal victories are important because they define our future as indigenous peoples; they are an important tool to guarantee our rights and our physical and cultural survival in our territories”

Young Kofan leader Alex Lucitante delivers a powerful message outside Ecuador’s Supreme Court during a press conference. The Ecuadorian Supreme Court, in November of 2019, selected the Kofan community of Sinangoe’s ruling for review in order to turn their victory into national jurisprudence for indigenous peoples across the country.

“Our territory is our home and we will not allow the State to destroy our territories and our existence. Our fight is not just for us as Waorani people. We are united in the same struggle with our brothers and sisters from other indigenous nations, such as the Shuar, the Schiwiar, the Sapara. We are fighting for our life and for the future generations. The government must listen to us and respect our decisions. We will continue to resist and unite!”

Waorani leader Nemonte Nenquimo, who was lead plaintiff for her people’s legal victory last year protecting half a million acres of their rainforest territory from oil drilling, speaks out during a press conference outside Ecuador’s Supreme Court.

Amazon Frontlines Lawyer Maria Espinoza speaks out during a press conference outside Ecuador’s Supreme Court: “These communities’ rights have been violated and their lives have been affected. The Supreme Court now has a historic opportunity in its hands, not only to review both Waorani and Kofan cases, but also to make a clear declaration on the right to free, prior and informed consent, a right which protects indigenous peoples from extinction”

“As Waorani elders, we have come to demand respect for our right to life. Our territories are not for sale”

– Omanca Enquiri, Waorani leader and elder (also known as a “Pekinani” in the Waorani people’s language). The Waorani people hope that their case will be selected, alongside the Kofan people’s case, to ensure that indigenous people’s rights to prior consultation and self-determination are guaranteed in accordance with the Ecuadorian Constitution and international law.

“This is not the first time we have come here. Our court ruling is not being complied with. Our lives are at risk. The Ministry of the Environment is not taking actions to protect or monitor our territory and mining continues to threaten our existence”

Kofan leader and President of the Sinangoe community, Edison Lucitante, speaks out to Ecuador’s Vice-Minister of the Environment inside their headquarters in Quito.

Women and Nature: Omnipresent But Invisible

Over the centuries many parallels have been drawn between women and the earth, starting with the age-old (and, for some, contested) Mother Earth, or Pachamama. More recently, the destruction of the earth for natural resource extraction has been compared with and attributed to the same underlying patriarchal forces as violence against women. Correspondingly, research has shown that environmentalism is perceived as un-masculine (Brough et al. 2016) and even that men are less likely to recycle than women because they are worried people will think they’re homosexual.

There is another parallel that deserves attention, but, due to its very nature, receives little – that of invisibility. Both women and ecosystems are often invisible in the same ways. Ironically, both are also omnipresent and so crucial. Omnipresent but invisible. Invisibility has dire consequences for the health of both women and ecosystems. This blog explores the ways that the perpetuation of this invisibility is structurally built into our institutions, societies and systems with a specific focus on consequences for Amazonian Indigenous women.

Women’s Invisibility

It will come as no surprise to readers to state that women are underrepresented in many spheres: politics, business, STEM (science, technology, engineering and math). Manuela Lavinas Picq’s (2014) in depth analysis of gender in Ecuadorian Indigenous politics points out that despite a discourse that advocates social justice and despite women’s prominence in indigenous struggles, Ecuador’s contemporary, Indigenous movement counts few women in its political leadership ranks.

Strong, female, indigenous leaders have broken through structural barriers throughout Ecuador’s history and fortunately are more and more frequent. In an early example, Tránsito Amaguaña, a Kichwa woman, helped set up the first Indigenous organization in Ecuador in the 1930s and, along with Dolores Caguango, was instrumental in the establishment of bilingual schools. In 1992, a historic march from Puyo to the capital, Quito, to fight for land rights was led by Kichwa women. More recently, in 2019, a women’s march in Brazil brought together hundreds of Indigenous and allied women to protest the destruction of the Amazon and the even more recent Indigenous mobilization against the International Monetary Fund-imposed austerity measures in Ecuador featured a women’s march. But we must not let the exceptions further blind us to the structural and systemic factors which keep women and issues important to them, for the most part, out of public purview.

Inspiring and promising exceptions exist – Here Nemonte Nenquimo, who is currently president of the Waorani political organization of Pastaza (Conconawep), leads her people in a pivotal lawsuit which recognized her people’s right to free, prior and informed consultation and suspended an auction which would have seen half-a-million acres of their pristine rainforest territory sold off to oil companies.

Nor should we fall into the trap of concluding that because women are not on the fore, they are not involved or are complacent. Women are key actors in Indigenous social justice and environmental struggles (Jenkins 2015), such as climate change. Feminist approaches to climate change are often holistic, systemic movements that address multiple environmental and justice issues at the same time (Rodriguez Acha, 2017). Further, women who are denied public tribune engage in powerful “everyday resistance” (Scott, 1985; Zanotti, 2013). Laura Zanotti (2013), in a study entitled “Resistance and the politics of negotiation: women, place and space among the Kayapó in Amazonia, Brazil” found that the everyday events and decision making processes that most villagers engage in can be as important to resistance movements as the highly visible, public acts that only a few leaders of the community participate in. Finally, western ideas of individualism, and even a feminist emphasis on autonomy and leadership, can obscure the ways in which indigenous women exert influence in their communities for the good of the collective, rather than angling for individual women’s rights (Figueroa Romero, 2018).

As the 2019 national Indigenous-led Ecuadorian mobilization highlighted “Making women visible as active participants in these struggles, and recognizing their strategic contribution, is particularly salient in the light of the increasingly violent and confrontational nature of state responses to such resistance.” (Jenkins 2015)

Tear gas, a chemical weapon, was the Ecuadorian police and military’s primary method to disperse crowds during the nationwide indigenous-led protests in October 2019

This gap between what is and what is seen exists across cultures and domains and it is also present in sectors such as sustainable forestry management (Elias et al. 2017) and health research. Karen Messing, a trailblazer of gender studies in occupational health, a field that largely considered women’s work as “light” and therefore without risk, wrote a book entitled “One-eyed Science” (1998) in which she lays bare the untold stories of women’s suffering at work and the structural issues that blind us to their suffering. More recently, Caroline Criado Perez (2019) exposes the gender data gap and reveals an invisible bias toward the male body. Her book is a startling litany of examples in which using “male” as default harms women: diagnosis of heart attacks, protective gear, and male-biased disaster warning systems. She calls this “male-unless-otherwise-indicated thinking.”

Numerous scholars and movements have also pointed out that women’s labor is widely unrecognized. They draw attention to women’s invisible role in housework, as caretaker, as food provider. To cite an Amazonian example, Susanna Hecht (2007) noted that in the Amazonian Rubber Boom context “the quotidian presence of toiling women in households was viewed as unremarkable, and so remained unremarked.” (p.324)

Women’s work is not “light” and is often repetitive, creating unique strain on the body. Here a Waorani woman carries her child and a wild boar back to the community, Yasuní National Park, Ecuadorian Amazon. Oil activity and the construction of oil roads have been severely detrimental to Waorani lands in the area

The powerful ‘#metoo’ movement has exposed the pervasiveness of violence against women. Violence most often occurs in private spaces – homes, hotel rooms, dark alleyways – out of view. The fear of reprisal and shame prevents women from calling out their aggressors, perpetuating a cycle of voluntary blindness on the part of some and fearful silence on the part of others. Research by the World Health Organization shows that the lifetime prevalence of violence against women in rural Peru is 61% (WHO, 2005). In the Ecuadorian Amazon, researcher Isabel Goicolea (2001) found that the single most commonly cited women’s health problem was ‘husband beats wife,’ cited by 84% of respondents.

Ecosystems’ invisibility

The corollaries between women’s invisibility and ecosystems’ invisibility are striking. Ecosystems do not have representatives in governments or advocates on boards of directors. Their streams burble and the wind rustles through their leaves all over the world, but there is a generalized hush about them in parliaments and board rooms in those very same places. Ecosystems are largely absent from public discourse, planning, and decision making. When and where the environment is present, it is mostly viewed as a natural resource to be exploited in production processes, not as an entity with inherent value.

In this sense, women and ecosystems can also be perversely conspicuous in the some of the same ways. While women’s bodies are objectified, landscapes are eyed for their resources. While women are prized for their reproductive services, ecosystems are valued when they are ‘productive.’

The Piatua River is one of the most beautiful rivers of the Ecuadorian Amazon. Earlier this year, the Kichwa people of Santa Clara won an important legal victory protecting the river from the construction of a hydroelectric dam, which threatened not only the river but also the Kichwa people’s way of life. Photo Courtesy Helena Gualinga

In some few instances and localities, people and systems are seeking ways in which the earth’s voice can be heard. For example, in 2008, Ecuador was the first country to enshrine the “rights of nature” in the constitution. Bolivia soon followed suit and since several countries, including New Zealand, Australia and India, have given legal rights to specific rivers (O’Donnell and Talbot-Jones, 2018). For years, the Ecuadorian edict remained quiet, until a series of court cases, including one brought to trial by the community of Sinangoe in 2018 against illegal mining, “activated” it. Nonetheless, Environmental Impact Assessments – the tool used by governments to evaluate the impacts of development projects on the health of the ecosystem – are too often done hastily, willfully turning a blind eye to the very factors that might impede the project.

Parallels also exist in the invisibility of the work that women and ecosystems carry out. Ecosystem ‘work’ is sometimes referred to as ecosystem services or the “subsidy of nature.” The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (2005) shone a light on these services, giving them names and classifying them as provisioning services (e.g. food), regulating services (e.g. wastewater treatment), supporting services (e.g. habitat) and cultural services (e.g. mental health). Similar to women in their households, ecosystems “toil” to provide us with clean water, food, fertile soils, and materials, while this work remains patently “unremarked.” Seeing the hidden services of nature is essential for developing best practices and effective resource policies that protect ecosystems and the services they provide (Raudsepp-Hearne et al. 2010).

Lindsay Ofrias (2017), argues that the widespread contamination of the Ecuadorian Amazon by oil is an ‘invisible harm’ in that the violence that it represents is unseen even though the actual contamination is often very obvious. She also contends that this ‘invisible harm’ leads to ‘invisible opportunities’ to companies in the form of cost-cutting and even, contentiously, silencing opponents through their oppression. This ‘invisible opportunity’ has its equivalent in the gender sphere in that as women are silenced, men and their voices can benefit. Similarly, in a piece about the process of First Nations-Settler reconciliation in Canada, Hiba Zafran notes that reflexive attention to which discourses are used to frame concerns is central, as certain languages and ways of seeing “…render[…] invisible, [and do] not provide a language for the mixed intentionalities of oppressors, and possibilities within oppressive systems.” (Zafran, 2019).

The “Not in my backyard” (NIMBY) syndrome is an expression of the religation of environmental violence to out-of-the-way places, whereby toxic waste sites and open pit mines are exceedingly more likely to be located in poorer neighbourhoods and communities. The #NoDAPL (Dakota Access Pipeline) movement was precisely about a push to eclipse the potential damage of a pipeline by moving its original path from the white-dominated town, Bismark, to the Indigenous reserve, Standing Rock (Estes, 2017). Similarly, Maurice et al. (2019) recently documented local people’s testimony of oil companies using antiquated and now-illegal disposal practices that release wastes directly into the Ecuadorian Amazonian environment, clandestinely under the cover of night.

At the interface of women's and ecosystems' invisibility

Many contaminants inflicting violence on the environment literally are invisible: mercury, lead, PCBs, endocrine disruptors, all cannot be seen with the naked eye. As Michelle Murphy so aptly puts it, “…the infrastructure of chemical relations that surround and make us largely resides in the realm of the imperceptible (Murphy 2006). We might feel some of our chemical relations and the pain they cause, but the fullness of our chemical relations ends up being largely conjectural” (Murphy, 2017, p. 496). She later makes the point that, in this post-industrial era, these contaminants are also ubiquitous (Ibid, p. 497).

Donna Mergler (2012), a Canadian researcher with 50 years of experience investigating toxic hazards, makes the case that different exposure to contaminants for women and men can be obscured if data is not disaggregated along gender lines, while differential impacts can be occluded if data is not analyzed separately by sex. For example, women in the Amazon were found to be exposed to mercury (Webb et al., 2016) and hydrocarbons (Webb et al., 2017) through their relationship with water, whereas other factors were considered more important in exposure for men. If the data had not been explored separately for women and men this relationship would never have been uncovered.

Research found that women's use of water - washing clothes and dishes, bathing children and cooking - put them in contact with toxic chemicals from the petroleum industry. These aquatic environments are subject to additional sources of contamination such as pesticide run-off from palm oil monocultures

Conclusion

These multiple layers of invisibility – gender, ecosystem, race and contaminant – add up to create a virtual opaqueness in which the complexity and nuances involved seem too daunting to disentangle and depict. This parallel of invisibility is no coincidence. As Sharlene Mollett and Caroline Faria (2013) point out, “Gender and race are a historically important coupling that shapes and is shaped by space. Take the “myth of virgin land” in former “colonies” where women, and land are posited in the colonial texts to be “discovered”, “named” and “owned” and where indigenous peoples are made invisible by male conquers.”

Pulling back the invisibility cloak shrouding women and ecosystems exposes the roots of some of the more symptomatic, societal ills. Admitting that there is a gender imbalance in negotiating tables, editorial boards, high stakes meetings, parlaments, top executives, panels, health data, and so much more is a first step to redressing this inequality. Recognizing and embracing women’s and nature’s perspectives could lead to major paradigm shifts, such as more collaborative decision making processes and laws that are conceived, built and applied with a view to conserving ecosystem health into the future.

While we should be wary of “pinkwashing,” we should celebrate the courage of women who break through structural barriers to project their voice. Women’s marches and coalitions, such as the one in August 2019 in Brazil, are so important in rendering the work and perspectives of women in the Amazon visible. It is not because the system is biased against heeding women and incorporating them into official decision making processes that they are not there carrying out crucial work in the struggle against injustice. The 2019 upheaval in Ecuador sparked by International Monetary Fund (IMF) imposed austerity measures is perhaps an illustration of a society in transition. Indigenous women were at the forefront of the protests on the streets, as many emblematic images made clear, however, when it finally came time to negotiate with the government they were conspicuously underrepresented. Interestingly, while the protests were triggered by economic factors, they quickly became about much more as Indigenous peoples began to pronounce on their territorial rights.

Let this be a rallying cry to each of us to recognize where gender enters into our lives and work and to name it. We, as a society – meaning both men and women – need to look for opportunities to amplify women’s voices, from youth to elders, multiplying the occasions for women to lead, express themselves and take action.

References

Brough, A. R., J. E. B. Wilkie, J. Ma, M. S. Isaac and D. Gal (2016). “Is Eco-Friendly Unmanly? The Green-Feminine Stereotype and Its Effect on Sustainable Consumption.” Journal of Consumer Research 43(4): 567-582

Criado Perez, C. (2019). Invisible Women: Data Bias in a World Designed for Men, Harry N. Abram.

Elias, M., R. Jalonen, M. Fernandez and A. Grosse (2017). “Gender-responsive participatory research for social learning and sustainable forest management.” Forests, Trees and Livelihoods 26(1): 1-12.

Estes, N. (2017). “Fighting for our lives: #NoDAPL in Historical Context.” Wicazo Sa Review, 32(2), 115.

Figueroa Romero, D. (2018). “Mujeres Indígenas del Ecuador: la larga marcha por el empoderamiento y la formación de liderazgos.” Canadian Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Studies / Revue canadienne des études latino-américaines et caraïbes 43(2): 253-276.

Goicolea, I. (2001). “Exploring women’s needs in an Amazon region of Ecuador.” Reproductive Health Matters 9(17): 193-202.

Hecht, S. B. (2007). “Factories, Forests, Fields and Family: Gender and Neoliberalism in Extractive Reserves.” Journal of Agrarian Change 7(3): 316-347.

Jenkins, K. (2015). “Unearthing women’s anti-mining activism in the Andes: Pachamama and the “Mad Old Women”.” Antipode 47(2): 442-460.

Maurice, L., F. López, S. Becerra, H. Jamhoury, K. Le Menach, M.-H. Dévier, H. Budzinski, J. Prunier, G. Juteau-Martineau, V. Ochoa-Herrera, D. Quiroga and E. Schreck (2019). “Drinking water quality in areas impacted by oil activities in Ecuador: Associated health risks and social perception of human exposure.” Science of The Total Environment 690: 1203-1217.

Mergler, D. (2012). “Neurotoxic exposures and effects: Gender and sex matter! Hänninen Lecture 2011.” NeuroToxicology 33(4): 644-651.

Messing, K. (1998). One-eyed Science: Occupational Health and Women Workers, Temple University Press.

Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. (2005). Ecosystems and human well-being: synthesis. Washington, DC.

Mollett, S. and C. Faria (2013). “Messing with gender in feminist political ecology.” Geoforum 45: 116-125.

Murphy, M. (2006). Sick Building Syndrome and the Problem of Uncertainty: Environmental Politics, Technoscience, and Women Workers. Durham, N.C., Duke University Press.

Murphy, Michelle. 2017. “Alterlife and Decolonial Chemical Relations.” Cultural Anthropology 32(4): 494-503. https://doi.org/10.14506/ca32.4.02.

O’Donnell, E. L. and J. Talbot-Jones (2018). “Creating legal rights for rivers: lessons from Australia, New Zealand, and India.” Ecology and Society 23(1).

Ofrias, L. (2017). “Invisible harms, invisible profits: a theory of the incentive to contaminate.” Culture, Theory and Critique 58(4): 435-456.

Raudsepp-Hearne, C., G. D. Peterson and E. M. Bennett (2010). “Ecosystem service bundles for analyzing tradeoffs in diverse landscapes.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107(11): 5242-5247.

Rodriguez Acha, M. A. (2017). “We have to wake up, humankind! Women’s struggles for survival and climate and environmental justice.” Development 60(1-2)((1-2)): 32-39.

Scott, J. (1985). Weapons of the weak: Everyday forms of peasant resistance. New Haven, CT, Yale University Press.

Webb, J., O. T. Coomes, D. Mergler and N. Ross (2016). “Mercury Concentrations in Urine of Amerindian Populations Near Oil Fields in the Peruvian and Ecuadorian Amazon.” Environmental Research 151: 344-350.

Webb, J., O. T. Coomes, D. Mergler and N. A. Ross (2017). “Levels of 1-hydroxypyrene in urine of people living in an oil producing region of the Andean Amazon (Ecuador and Peru).” International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health 91(1): 105-115.

WHO (World Health Organization) (2005). WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence against women: summary report of initial results on prevalence, health outcomes and women’s responses. Geneva, World Health Organization.

Zafran, H. (2019). Ecopoetics and unbelonging: Shaping ground within Indigenous partnerships. [Workshop presentation]. Paper presented at the Advanced Study Institute in Cultural Psychiatry: Cultural Poetics of Illness and Healing: Embodiment, Enactment and the Politics of Experience, Montréal, QC

Zanotti, L. (2013). “Resistance and the politics of negotiation: women, place and space among the Kayapó in Amazonia, Brazil.” Gender, Place & Culture 20(3): 346-362.

List of Chronicles in our Health on the Frontlines series:

Nothing found.

Pëëkë’ya (Lagartococha): Journey To Our Spiritual Origin

In August of this year, over 50 women, men, elders and youth from the Siekopai (Secoya) nation of the Ecuadorian Amazon embarked on a historic five-day canoe journey and paddled 160 kilometers (100 miles) to the sacred lagoons of Ñakomasira, the heartland of their ancestral territory – Lagartococha – on the border between Peru and Ecuador.

In the following story, indigenous photographers Jimmy Piaguaje and Ribaldo Piaguaje from the Siekopai nation share moments and memories from their incredible journey within this mega-diverse labyrinth of blackwater lagoons, flooded forests and rolling hills. Their photos follow their trip, as they fished along the river, slept on the beaches, visited historic places, shared ceremony with their elders, and learned about the history and ancestral lands of their people.

Their journey marks an important step forward as part of the Siekopai’s struggle to reclaim sacred lands they were forcibly displaced from during a border-war in the 1940s between Peru and Ecuador, and the Siekopai’s attempts to return have all been derailed by a lack of formal land rights within what is now a national park. As they fight for Lagartococha, an area so critical to their physical and cultural livelihood that without it their existence is imminently threatened, the Siekopai hope to pave the way for other indigenous nations to do the same.

The Lagarto River, named for the abundance of alligators within it, slithers and weaves through black water lagoons that reflect the forest, like a mirror hidden deep in the Amazon on the border between what are now the territories of Ecuador and Peru.

This territory is the spiritual center of our ancestors, it is the cradle of our yage (ayahuasca) drinkers and our connection with the aquatic world. Lagartococha is the spiritual origin of our people – the Siekopai, the Multi-Colored People.

From the time war broke out in 1941 between Peru and Ecuador, our people were forcibly displaced, and many of our families were separated. We were uprooted from our ancestral territory. Today, in Ecuador, we live in a small territory surrounded by oil companies, roads and the African palm industry, nearly 200 kilometers upriver from where our grandparents were born and raised.

RECLAIMING OUR SACRED LANDS

But we, Siekopai, have always kept the memory of Lagartococha alive. It is here that the bones of our ancestors rest. Our elders still recount the stories of our ancestors who navigated along the waters of Lagartococha. This is why we are fighting for the Ecuadorian government to recognize our right to our ancestral territory. For many generations, our people have been dreaming and fighting to recover their ancestral territory.

And so we began this journey in order to make our struggle visible to others. Our elders shared with us their stories, their legends and their knowledge about our ancestral territory, and in this way, the youth of our nation reconnected to the territory of our ancestors.

Each day, our elders’ voices would wake us up in the early hours of the morning before dawn. They summoned us to drink yoko, a beverage made from the scrapings of a vine. Drinking yoko gave us energy, courage and strength, while we listened to the stories and advice of our elders for the days ahead.

Lagartococha is a magical place. It is full of life. The forest is thick and it is home to a great diversity of animals. For us, Lagartococha is not only a place of great spiritual importance, it also provides us with our subsistence. The forest gives us fruits and many medicinal plants, and the river abounds with fish to feed our families.

“Pëëkë’ya – Lagartococha

is our territory, our blood, our birthplace, the foundation of our cosmovision. The bones of our ancestors rest there. Since 2017, we have demanded that the Ecuadorian government gives us ownership over these lands. We have legal, geographical and anthropological evidence demonstrating that this 100,000 acre territory is ours. Today, we are only 600 Secoya left in Ecuador and at risk of disappearing culturally and physically.”

– Justino Piaguaje, Siekopai leader and President of the Siekopai nation of Ecuador

For many children and young people, this journey marked their first visit to Lagartococha. It was a very special experience, and we felt a lot of happiness when some of our families were reunited with their relatives on the Peruvian side of our ancestral territory.

After five days of sharing stories and visiting ancient village sites, burial grounds, and sites of ceremonial lodges while listening to the experiences of our parents and elders, we arrived to the legendary and sacred Ñakomasira (Wounded Eye) lagoon, which is home to several beings and spirits of the aquatic world.

Our canoe journey to Lagartococha will be forever engraved in the memory of our nation’s young generations. These are important steps to recover our memory as a people, and to unite ourselves in order to ensure that the legacy of our ancestors can continue to be passed down from generation to generation. We want to maintain our spiritual connection with the place of our origins. As young people, we will continue this struggle to recover our roots, so that the future generations do not forget and understand what it means to be truly Siekopai.

Between Ashes and Hope: Bolivia’s Amazon Fires Through The Lens of Two Young Indigenous Photographers

“War and fires have much in common. It is not known how or when they begin, or how they will end. The only certainty is that the spark and fuel are human’s greed and ambition, and this is caused by lack of understanding and fear. Like all wars, fire only brings us sadness, pain and disease”

– Alcides V., an activist from Chiquitanía, Bolivian Amazon, September 2019

With their cameras loaded, two young indigenous photographers and filmmakers from the Ecuadorian Amazon began the long journey to the Bolivian Amazon amidst the fires. Jimmy Piaguaje and Ribaldo Piaguaje were headed to Chiquitano, in the country’s fire-ravaged lowlands of the southern Santa Cruz region.

The destruction of millions of acres of primary rainforest in the Bolivian Amazon by the fires are part of a global crisis and assault on the Amazon rainforest’s resources, and the lands and rights of indigenous peoples. Between May and September 2019, the world’s headlines were gripped by the apocalyptic images of burning forests across Bolivia, Brazil and Paraguay. The vast majority of the fires were intentional, and were fueled by the policy changes and agendas of governments in the region encouraging deforestation and promoting agribusiness and extractive interests at the expense of the rights of indigenous people and conservation. Today, indigenous people’s resource-rich rainforest territories are more threatened than ever by land grabbing, invasions, and deadly violence.

In this unique photo reportage, indigenous youth Jimmy Piaguaje and Ribaldo Piaguaje, along with members of Amazon Frontlines’ communications team, take us on a journey to investigate and experience the frontlines of the fires in the Bolivian Amazon and meet the affected communities, through their eyes, perspectives, and memories.

I. Meet Indigenous Communicators Jimmy and Ribaldo

“We wanted to hear from the people affected by the fires.”

My name is Jimmy Piaguaje, I am a member of the indigenous Siekopai nation. I live in the northern Ecuadorian Amazon. I dedicate myself to community media and communication by creating films, documentaries and photography in order to strengthen the oral memory of my people. For over fifty years, our ancestral territory has been affected by the presence of oil companies, the construction of roads, and more recently, African palm plantations.

My name is Ribaldo Piaguaje and I am also an indigenous youth of the Siekopai Nation in Ecuador’s Amazon. I am passionate about photography, video and audiovisual editing. I like to tell the stories of my grandparents and ancestors through these media, and show how extractive interests have divided and threatened our people, without respect for our will and our needs.

Over the course of several months, we had been seeing a lot of news about the fires in the Amazon. We really wanted to understand the problem, and we wanted to hear directly from the people whose communities had been affected by the fires, in order to understand the real causes and impacts.

II. The Landscape (Agroindustry)

“The environment seemed almost lifeless.”

We arrived at the city of Santa Cruz, an Amazonian frontier town in Bolivia, and one of the closest cities to where the fires were burning. We were on our way to Chiquitanía. Along the way, we were surprised by the hundreds of acres of land deforested for livestock, and large monocultures of soya, sunflower and grains.

The cracked soil looked poor and dry. Nearly all the plants were dead. Just a few isolated trees provided a few meters of shade for the earth. It was much hotter and less humid than in our rainforest home, and the water had disappeared from the landscape: there were no rivers or swamps. The environment seemed almost lifeless.

As we traveled deeper into the Chiquitana region, we saw the blue sky of Santa Cruz turn gray with smoke, and we saw the devastation left by the fires along the road.

We asked ourselves, how is it possible that a country such as Bolivia has let such a disaster happen on its lands? Why were these fires happening? Who was lighting them and why?

III The Fires

“The fire consumed everything before our eyes.”

After traveling a few hours inside the dry forest, we arrived to a giant fire raging across thousands of hectares of the Chiquitano forest. The fire reached up into the sky some 6 to 8 meters and its immense columns of smoke eclipsed the sun.

As the fire rapidly progressed, birds fled by the flock, and a trail of calcinated animals and insects that tried to escape in vain was left in its wake. Only heat and smoke filled this new hostile and desolate environment.

Within a matter of hours, the fire had consumed everything. The patient work of nature, over hundreds of years, had just disappeared before our very eyes.

In the community of San Agustín, we listened to the testimonies of community members who had been fighting the fierce fires for weeks, with simple tools such as fumigation bombs, sticks, and machetes.

In several places, the fire surrounded their houses. We could feel their worry and despair. They were tired of working struggling against the fires and government aid was scarce.

Indigenous peoples’ efforts to combat these fires were impressive. They sometimes walked all night in the forest carrying several gallons of water to extinguish the fires, taking the work in turns throughout the day.

Local efforts to combat the fires were supported by the military, council members and police, as well as volunteers from civil society across Bolivia.

IV. The Ashes

“What had once been forest was now only ashes”

We found a burned herd of badgers (coatí, nasua nasua) that seemed to be trying to flee together. We felt an emptiness, and we smelled burned flesh in the air. It was as if something had been ripped out of our hands. Sadness, anger, and despair overwhelmed us.

A grandmother told us how she remembered her community 20 years ago: “Before we had many animals and birds, and fish abounded in the rivers. The forest is our mother who gives us food, but today the river is dried up, many of the animals are gone, and we don’t even have drinking water.”

“What are we going to eat? What will our children eat tomorrow? And what about our animals?”

Ignacia invited us to visit her chaco (chakra, traditional garden). Her crops were burnt down. Coffee, bananas, cassava, medicinal plants and other produce were consumed by the fire

“The weather has changed completely”, she told us with tears in his eyes. We watched with indignation as the community members made a hole in the ground with hopes of finding muddy water for their cattle.

That day, we understood the difficulties that this indigenous community faces. A small truck delivers 6 liters of water per family – for the whole week.

V. Indigenous People’s Resistance

“Indigenous people want their voices to be heard”

Half way through our journey, we found ourselves marching in an indigenous mobilization heading hundreds of miles towards the regional capital of Santa Cruz de la Sierra. The march voiced people’s discontent with the State’s policies regarding land use, excessive colonization, forest fires and agricultural frontier expansion, and demanded that a state of emergency be declared in indigenous people’s ancestral territories affected by the fires.

Indigenous people wanted their voices to be heard. They were speaking out against the exploitation and looting of their territories by big cattle ranchers, agribusinesses and loggers.

VI. The Struggle To Protect The Amazon Continues

“The battle has not yet been lost.”

We were very moved by the experiences we lived alongside so many people during this trip. We now know that the Amazon may dry up in the future if the rights of indigenous peoples, their territories, and ways of life are not respected.

We are afraid to imagine an Amazon without water, without our own crops, without rain, without animals, without abundance, without life. Despite the distance between our territories, we now know that we have so much in common, and we clearly see that indigenous peoples have always been and will continue to be the guardians of Mother Earth – even despite the difficulties we face.

We need to become conscious of what is at stake, listen, understand and shine a light on these real problems in order to transform the world. As young indigenous people, we demand that they stop destroying the forest. We want people to understand that our life and planet depend largely on the Amazon, and that we all depend upon the land to live healthfully and well. We also don’t want our peoples to be forgotten. This struggle is just beginning, and the days ahead are even harder and more disturbing.

As indigenous peoples of the Ecuadorian Amazon, we say to our brothers and sisters in the Bolivian Amazon: “Let the struggle continue! Let us defend our forest until the end, even risking our lives. Your ancestors and our ancestors lead the way. Let’s keep resisting in this battle, it has not yet been lost.”

United Nations Pays Tribute to Waorani People’s Victory on Indigenous Peoples Day

United Nations Pays Tribute to Waorani People’s Victory on Indigenous Peoples Day

Today, on #IndigenousPeoplesDay, the United Nations released a special video paying tribute to the inspiring struggles of the Waorani people, and all indigenous nations, in the battle to protect their lands, their way of life, and our shared climate from the mounting threats of a global economic system premised on the limitless extraction of natural resources.

“The Waorani people have defended their land for generations. They won a legal battle but their struggle isn’t over. On #IndigenousPeoplesDay, they ask us to unite and fight.” – Message from the United Nations.

In the tribute video, Nemonte Nenquimo, Waorani leaders, says: “We want to give a message to the world. We need to unite in the struggle because the fight is not only up to indigenous people but for all of humanity. We have to sustain our planet. Everyone is talking about climate change. That is what we have to do: Unite to save our planet.”

The Secoya, Siona, Kofán and Waorani indigenous nations featured in the video have lived for half a century with the impacts of oil. They have united to form an alliance, the first of its kind in their history, to protect their lands and way of life. This union has been instrumental in saving half a million acres of the Waorani’s land from oil drilling. In the words of a young Kofán leader, “We have united with our Waorani brothers and sisters because we share the same struggle and dream: to protect our forest and to continue being who we are, as indigenous peoples.” Check out this Chronicle to learn more about how this alliance worked together to defend the Waorani’s forest.

Nemonte is right. Only through unity can we overcome problems as big as the destruction of the Amazon and our planetary climate crisis. Join the indigenous nations in defense of indigenous life and one of our planet’s greatest natural treasures.