An unprecedented legal victory for indigenous rights in Ecuador frees up huge swath of Amazonian rainforest from gold mining

On October 22nd 2018, the Kofan people of Sinangoe in the Ecuadorian Amazon won a landmark legal battle to protect the headwaters of the Aguarico River, one of Ecuador’s largest and most important rivers, and nullify 52 mining concessions that had been granted by the government in violation of the Kofan’s right to consent, freeing up more than 32, 000 hectares of primary rainforest from the devastating environmental and cultural impact of gold mining. This precedent-setting decision will inspire indigenous nations across the Amazon and land defenders worldwide for years to come.

The Kofan people of Sinangoe, with the support of Amazon Frontlines and the Ceibo Alliance, have been successful in forcing the Ecuadorian government to cancel all mining concessions on and around their ancestral land, a groundbreaking victory for indigenous rights in Ecuador.

In a historic ruling, the Provincial Court accepted evidence of environmental impacts provided by the community of Sinangoe and the provincial ombudsman, charged the government with not having consulted the Kofan, denounced the mining operations for having violated indigenous rights to water, food and a healthy environment, and cancelled all mining activity in more than 52 concessions at the foothills of the Andes. The ruling, which cites the precautionary principle and uses Ecuador’s new law on the rights of nature, also forces authorities to set in place restoration measures in an area that had been already heavily impacted by the mining operations.

“This is a great victory for our community, for our people and for all indigenous peoples. We are not just fighting for our people, but for everyone who depends on clean water and clean air. This victory is a huge step forward for our children and for future generations. We will remain vigilant in our territory and will continue fighting until we have legal title over our entire ancestral homeland.”

– Mario Criollo, President of the community of Sinangoe.

After only 4 months of mining operations, the environmental damages we have witnessed and documented for the court case provided a strong set of evidence on how granting mining concessions in such a fragile and rich environment is totally incompatible with the Kofan way of life and the conservation efforts needed in this biodiversity hotspot. The area now freed from mining activity is one of the most biodiverse areas on Earth. It is home not only to the Kofan people who depend on its fresh water for survival, but also to more than 3,725 species of plants, 650 species of birds and 50 species of mammals.

Mining operations threaten profound and irreversible environmental and cultural damage in this ecological hotspot as well as the health of the people of Sinangoe and thousands of people in dozens of indigenous communities downstream. Further exposing this highly diverse primary forest to uncontrolled deforestation would also accelerate the global climate crisis.

The headwaters of the Aguarico River, at the core of the Kofan ancestral land and one of the main artery of the Ecuadorian Amazon, were threatened by mercury and cyanide pollution commonly used in gold mining operations in the Amazon, until the Kofan successfully blocked it by suing the Ecuadorian government.

After months of ongoing land patrols, the use of camera traps, drones and satellite imagery, as well as indigenous-driven media campaigns to raise awareness of destructive mining practices, the Kofan people, with the support from Amazon Frontlines and our indigenous partners from the Ceibo Alliance, have succeeded in demonstrating the importance of indigenous-led environmental monitoring and sustained innovative legal strategies to protect their land and rights. Sinangoe now has the important task of ensuring the ruling is respected and the measures dictated by the Courts are enforced on the ground.

“This is a major win for indigenous rights in Ecuador, and a huge wake up call to the Ecuadorian government. Before viewing the land for the minerals underneath it, the Courts now forces authorities to obtain consent from the indigenous peoples who call it home, and to properly evaluate the environmental and cultural costs of allocating such biodiverse hotspots to gold miners.”

– Maria Espinosa, Amazon Frontlines’ legal coordinator and Sinangoe’s lawyer.

List of chronicles in our series on Sinangoe:

Nothing found.

Deforestation in the Ecuadorian Amazon: 50 years of oil-driven ancestral land invasion

When I started doing research on deforestation in the Ecuadorian Amazon back in 2001, it was almost impossible to get a clear idea of where and how large the deforestation frontlines in this corner of the Amazon were. The information was scarce, not easily accessible, and often not credible.

However, some alarming clues were already out there. One was from the scientific community, which, back in 1993, had identified the Napo River Watershed, in the heart of the Ecuadorian Amazon, as one of the most active deforestation fronts in the tropical world (namely the Napo Deforestation Front). A bit later, in the mid 2000’s, scientists warned that Ecuador had the highest deforestation rate in South America. At that time, even with the limited information available, it was clear that this mega bio-diverse rainforest was under great pressure.

The oil industry has been the main driver of deforestation in the Ecuadorian Amazon for decades. Roads and pipelines to access oil installations, like this one built by the Chinese Oil giant Andes Petroleum close to ancestral Siona lands, are the typical first blow to rainforest integrity with colonization following suit.

But it was only by traveling throughout the region, and actually crossing the frontlines of deforestation, that I finally witnessed what was really going on: aggressive intrusions into pristine indigenous lands were being mostly driven by the expansion of the oil industry since the 1970’s, through the construction of roads, pipelines, wells, pools, seismic lines, camps and heliports, which, once constructed, led to a second wave of deforestation through rapid colonization and the establishment of pastures.

That was more than 17 years ago.

Once a road is built in the Amazon, both climate and biodiversity are profoundly impacted due to the very nature of this carbon-rich megadiverse ecosystem.

Witnessing a cultural and biological catastrophe in real time

Since then, the expansion of the industrial footprint hasn’t stopped – on the contrary, it has grown (although Ecuador is not the worst of all Amazonian countries). For example, the Ecuadorian Amazon is now crisscrossed by more than 9500 km of roads – or 1.5 times the Earth’s radius – built for pipelines, in order to connect more than 3430 oil wells and to provide access to new pristine areas. New studies also show that the patterns of deforestation in the Amazon are shifting from large blocks to widespread small patches, increasing threats both to climate and biodiversity.

But one positive development is that technologies, satellite images and scientific research have given us a much better understanding of the scale and the impacts of such rapid forest degradation. Now, with just a few mouse clicks, you can see years of satellite data revealing the blows of deforestation. With so much information readily at hand, it has become impossible for industries and the Ecuadorian government to hide their environmental record.

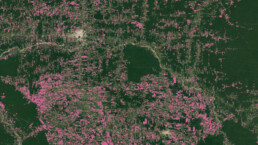

The interactive map from Global Forest Watch shows over 14 years of deforestation in the Ecuadorian Amazon, a very useful free online tool for anyone interested in looking into these issues.

In its 2014 publication on deforestation-driven greenhouse gas emissions submitted to the United Nations, Ecuador declared having lost more than 475,000 hectares of primary Amazon rainforests from 1990 to 2008 Four months later, the country had to readjust its statistics because it had apparently underestimated early 2000-2008 Amazonian deforestation by 25,000 hectares, for a total of 499,000 hectares lost in the Amazon since 1990. If we add up deforestation measured by satellite from 2008 to 2016, the Ecuadorian Amazon has lost 650,000 hectares of pristine rainforest. This represents a massive encroachment on ancestral lands of many indigenous communities at an average pace of 110 American football pitches of forest cleared every day from 1990 to 2016.

Unfortunately, with 68% of the Ecuadorian Amazon divided into oil blocks, Ecuador is planning to push the frontiers even further in 2018 and the years to come, opening up new oil blocks for seismic testing and drilling in the southern Ecuadorian Amazon inside Waorani, Sapara, Achuar and Shuar lands, amongst others. With oil operations already inside iconic protected areas like the Yasuni National Park and the Cuyabeno Wildlife Reserve, it seems like the Ecuadorian government is on a reckless crusade to extract the last drops of crude oil out of the Amazon.

Defending land rights leads to forest protection

Remarkably, despite these waves of deforestation and colonization, pockets of forest are still standing. Research shows that the presence and recognition of ancestral indigenous peoples and territories is amongst the greatest obstacles to deforestation, forest degradation and climate change. Deforestation in the indigenous lands of the Amazon is known to be 2 to 3 times lower than outside recognized ancestral lands.

Amongst the many indigenous peoples of the Ecuadorian Amazon whose ancestral lands are under siege from rampant deforestation and the expanding oil industry, the A’I Kofan community of Dureno is a living testimony of the central role indigenous peoples can play to block deforestation.

When overlaying primary forest cover with boundaries of indigenous ancestral lands in the Ecuadorian Amazon, one can see how indigenous communities are shielding the forests. The case of Dureno, a 10,000 hectare Ai’Kofan territory with an estimated diversity of more than 2,000 plant and 400 bird species, is quite striking. Surrounded on all sides by roads and pipelines, the community has defended its land and avoided the spread of roads into its forest, leaving an island of untouched forest amidst an ocean of oil wells, pipelines and pastures.

Despite constant encroachment on their ancestral lands, indigenous people of the Ecuadorian Amazon, like the A’I Kofan of Dureno, are still standing strong to defend the last of their pristine forests and block deforestation (source: Global Forest Watch).

Working in direct partnership with indigenous communities is at the core of our mission, and while pressures on land, forests and culture are constantly expanding, so are the abilities of indigenous people to take leadership, build networks and shape the resistance. The battle to stop deforestation in the Amazon is the battle to defend indigenous rights to their ancestral lands and cultures. And in return, these forests are amongst our best shields against catastrophic climate disruption, so this fight is of concern for all of us on a global scale. Will you fight with us?

Support our work to protect the Amazon and halt the expansion of extractive industries into ancestral indigenous territories by donating here.

List of chronicles about Deforestation:

Nothing found.

Be a Champion for the Amazon!

Start a fundraising campaign to drive resources to Indigenous Earth Defenders on the frontlines

The Kofan people ramp up the fight to protect one of the most biodiverse forests in the Amazon

In January 2018 the Ecuadorian Government concessioned off over 30,000 hectares of some of the most bio-diverse rainforest in the Amazon to an array of mining interests, precipitating a gold-mining boom in the ancestral lands of the Kofan people. There were no prior meetings. No consultation. No information provided to the Kofan villagers of Sinangoe. No permission was asked. The arrival of big machinery, water pumps and dozens of miners was the only courtesy the government gave the ancestral guardians of this biodiversity hotspot.

After months of ongoing land patrols, the use of camera traps, drones and satellite imagery, as well as innovative legal strategies and indigenous-driven media campaigns to raise awareness about destructive mining practices, the Kofan people are on the verge of winning a landmark legal battle to protect the headwaters of the Aguarico River and contribute to the national movement to strengthen collective rights to Free, Prior and Informed Consent over any extractive activity in indigenous lands.

Over 30 000 hectares of mining concessions were granted by the Ecuadorian government in the headwaters of the Aguarico River, Ecuadorian Amazon, without any Free, prior and informed consent from the Kofan community of Sinangoe.

The Kofan peoples’ ancestral rainforest homeland is a miracle of biodiversity – a headwater region where Amazonian forest ascends steep mountainous cliffs into the Andean foothills, home to more species per hectare than anywhere else in Ecuador. The Kofan people, recently featured in a Foreign Policy story about the advantages of indigenous land stewardship, are achieving international recognition for their conservation efforts – which combine cutting-edge tech, weekly land patrols, and tenacious legal advocacy.

Yesterday, the Kofan people’s efforts received an additional boost with a strongly worded letter to Ecuador’s president, Lenin Moreno, signed by 55 national and international organizations, including Greenpeace, Hivos, Amazon Watch and Rainforest Fund. The support comes after the community won a first legal battle in court against four Ecuadorian ministries back in July 2018. In this ruling, a regional judge recognized that Sinangoe’s right to free, prior and informed consent had been violated, and suspended all mining operations in the Aguarico headwaters.

“The presence of mining in the headwaters of the Aguarico River represents a threat to the health of the people of Sinangoe and thousands of people who live downstream, exposes this highly diverse primary forest to uncontrolled deforestation and accelerates the global climate crisis.” – Letter to Lenin Moreno, President of Ecuador

The decision in the lower courts was immediately appealed by all the authorities, and then by Sinangoe and their ally in the Defensoria del Pueblo, who seek an even tougher verdict recognizing that rights to health, water and a clean environment had also been violated and also that the concessions be revoked, not just suspended. The case will be brought in front of provincial judges tomorrow, September 5th 2018, where hundreds plan to gather at the Court of Appeals in the amazonian town of Lago Agrio, coming in support of the Kofan Nation and in defense of the Aguarico River, its pristine headwaters and the vital water it provides to thousands of amazonian people. Stay tuned for more on Sinangoe’s struggle.

List of chronicles in our series on Sinangoe:

Nothing found.

Historic indigenous legal victory against gold mining in the Amazon

In a lawsuit that will inspire and galvanize many other indigenous communities across the Amazon for years to come, the Kofan of Sinangoe have won a trial against four Ecuadorian ministries and agencies for having granted or attempted to grant more than 30,000 hectares of mining concessions in pristine Amazonian rainforest on the border of their ancestral land without their free, prior and informed consent. The destructive mining operations that were taking place within these concessions threatened not only the Kofan’s lives, culture and health, but also those of the countless communities located downriver.

In a historic decision on Friday July 27th 2018, a regional judge accepted the evidence provided by the community, charged the government with not having consulted the Kofan, and suspended all mining activity in more than 52 concessions in the headwaters of the Aguarico River. The decision was immediately appealed by all the authorities involved, and then by Sinangoe and their ally in the Defensoria del Pueblo, who seek an even tougher verdict recognizing that rights to health, water and a clean environment had also been violated. The case will be brought before a provincial judge in August, 2018.

The free, prior and informed consent loophole

Like in many places around the world, the Ecuadorian government has a mining claim system built to facilitate any interested party in purchasing cheap concessions— maximizing foreign interests and accelerating the approval process. Although both Ecuador’s Mining Act and the Constitution recognize the need for Free, Prior and Informed Consent from stakeholder communities for mining operations, it is still mostly a theoretical concept ignored by Ecuadorian agencies. Hence Sinangoe’s lawsuit. According to the experts heard over the course of the legal process, the Mining ministry leaves the “consultation” to the mining company or the concession owners themselves, which in turn have no legal obligation to consult with local people, and often will perform their “consultation” through a phone call or by handing out a simple information pamphlet. In the case of Sinangoe, it was when machines started tearing up the riverbed of the Aguarico looking for gold that the community learned about the new concessions.

The entire length of the Kofan River, a symbolic water body that crosses Sinangoe’s land, has been sold to gold miners by the Ecuadorian authorities without prior and informed consent. Mining in this area would cause dramatic environmental and cultural damage.

The Environment ministry, on the other end, stipulated in the courtroom that it is not responsible for consulting with communities impacted by mining. Interestingly, according to the Mining Act, the Environment Ministry needs to grant environmental licenses before operations can begin, unless the granting process takes more than 6 months, in which case – as unbelievable as this is – the permits are automatically granted to the operators. So basically, via a very simple bureaucratic process involving nothing more than paperwork, a mining operator can very quickly obtain 20 to 25-year land claims within 6 months, while the impacted communities living downstream haven’t even heard about the concessions. This is a loophole the judge described as a violation of the right to free, prior and informed consent, a verdict that will help many other communities facing the same threats in a country where gold mining is booming.

When rigorous community monitoring pays off

Throughout the lawsuit, the ministries’ lawyers vigorously tried to destroy Sinangoe’s evidence, credibility, ownership of and ancestral claims to the land. They downplayed the environmental damage documented by Sinangoe, claiming that the Kofan aren’t impacted by the mining operations because their land is on the other side of the river and that legal mining has minimal footprint on the environment. However, Sinangoe had done what will likely inspire many other communities: they had documented every step made by the miners through rigorous and systematic monitoring using high tech mapping, filming, archiving all evidence, and then they used legal tactics to pressure every single level of government to act to stop the operations. Systematic recording of all the different types of evidence helped build a solid case against a negligent concession-granting system.

Once in the courtroom, Sinangoe had accrued such a massive body of evidence of environmental damage and inaction on the part of the government that the judge requested a field inspection, a key event that helped him understand the scale of the damage already done, showed the deep connection the Kofan have with the area transformed into mining concessions, discredited the ministries’ arguments, and also allowed him to witness the sheer beauty of the area at risk.

A first legal victory, but the battle for land and rights still rages

To the officials sitting in their offices in Quito, these concessions were nothing more than coordinates and squares on a map, but to the Kofan who live across the riverbank, the area is a place imbued with life, history, sustenance, stories and so much more. To grant concessions without experiencing the place in and of itself, either through field visits or proper consultation with the people who inhabit and use the territory, is a transgression of the inherent value of sites so rich in history and biodiversity.

Sinangoe’s strength has been put to trial, and the community’s perseverance and conviction have provided them a first legal victory and attracted support from various indigenous and human rights organization across the country. With all ministries involved appealing the judgment, the Kofan will need more strength and support to navigate the next wave of legal governmental intimidation.

Sign the pledge in support of Sinangoe and stay tuned for more on our work to defend rights, lands and life in the Amazon.

List of chronicles in our series on Sinangoe:

Nothing found.

Sinangoe Takes Its Fight to the Courtroom

From December 2017 to February 2018, the Ecuadorian government granted more than 10 new gold mining concessions in the headwaters of the Aguarico River— a major tributary of the Amazon River and vitally important to dozens of indigenous communities downriver— most within the boundaries of the Cayambe-Coca National Park and home to ancestral Kofan people of Sinangoe. Despite its direct impact on the community, the rivers, the land and the Kofan way of life, the new mining claims were granted without any free, prior and informed consultation with Sinangoe. Miners even began operating without an environmental license or water permits and have been illegally mining outside of the concessions.

In order to defend their territory and the other indigenous communities threatened by these mining operations, Sinangoe, Amazon Frontlines and our partner organization Ceibo Alliance, organized a land patrol, training dozens of community members in GPS mapping, video, photography and even the use of aerial drones to document illegal incursions into the Kofan’s legally-titled lands. These land patrols covered thousands of hectares on foot through densely forested mountain trails and by canoe up challenging and treacherous rapids, capturing critical evidence of illegal mining activities. You can learn more about the land patrols and their efforts to combat mining from our Amazon Chronicles blog: here, here and here.

On Tuesday, an article written by a journalist who was embedded with the Kofan land patrols was published in Foreign Policy magazine. The piece presents the complex relationship between indigenous peoples and national parks, making the argument that indigenous stewardship is far more effective at protecting delicate ecosystems than turning these areas into national parks managed by the government. The Kofan people of Sinangoe are a strong example in favor of this argument. Empowered and supported with tools and training, the Kofan are defending their lands from 21st Century threats with a resolve born from their intimate and ancient connection to the land. For the Kofan, protecting this forest and these rivers is not based on a distant notion of carbon markets or UN recommendations, it is a struggle to protect their way of life passed down from their ancestors, their health and their children’s future.

Now, the Kofan are taking their battle into the courtroom. This Thursday, July 19th, the Kofan go to court against the Ecuadorian Ministry of Mining, the National Mining Regulation Agency, the Ministry of the Environment and the Secretary of Water to revoke mining concessions along the border of their land and prohibit the mining companies that have systematically violated their rights from continuing to operate. At Amazon Frontlines, we will continue our efforts to raise awareness about the Kofan’s courageous battle to protect their territory. In the meantime, sign and share the pledge to #StandWithSinangoe and help strengthen the indigenous movement for resistance and rainforest conservation– on indigenous peoples’ terms– at the headwaters of the Aguarico River.

List of chronicles in our series on Sinangoe:

Nothing found.

Hit & Run from Illegal Miners

The “fluorescent” orange water coming out of the ground and flowing towards the pristine headwaters of the Aguarico River smells like a mix of sulfur and dead animals. The landscape has been ravaged, the jungle is gone, the ground has been turned inside-out, and the Provincial Prosecutor looking at the scene has trouble hiding his discomfort in front of such obvious evidence of illegal mining. This authority, the highest in the Northern Ecuadorian Amazon, is part of a delegation of the Environmental Police, the Ministry of Environment, the Ministry of Mining and the Ecuadorian Mining Regulation Agency who joined the Kofan land patrol of Sinangoe in a field visit where illegal miners had been wreaking havoc for 5 months already in this remote corner of the Amazon without being caught or sanctioned by authorities.

Alex Lucitante, a Kofan leader and human rights defender from the Ceibo Alliance, shows the Provincial Prosecutor and Ecuador’s Environmental Police a contaminated creek coming from illegal mining heading towards the Aguarico River.

Alex Lucitante, a Kofan leader and human rights defender from the Ceibo Alliance, shows the Provincial Prosecutor and Ecuador’s Environmental Police a contaminated creek coming from illegal mining heading towards the Aguarico River.

After a quick boat ride against the Aguarico’s treacherous white waters, the delegation has come to a full stop on a site that only a week ago was teaming with goldminers, excavators and water pumps. Sinangoe’s land patrol, with the support of Amazon Frontlines and the Ceibo Alliance, have found out in recent months that more than 70% of the mining operations were conducted outside of the mining concession granted by the Mining Regulation Agency back in February 2018. While the authorities observe the scene, the Kofan land rangers point to the areas where the mining camps were located the last time they had come to do their weekly patrol, but this time, only garbage and a leftover fire camp could be seen.

Described in a previous blog as a new gold rush area, the headwaters of the Aguarico have been divided into more than 30 000 hectares of mining concessions without any free, prior and informed consent from the Kofan Nation or any of the impacted communities, triggering a vast movement of solidarity and support to Sinangoe by other affected indigenous Nations living downstream. On the site, signs of illegal use of chemicals are obvious where open pools have been left untouched, those holes a clue of gold mining likely utilizing cyanide on this very site the week before, giving the riverbank a disquieting look. Along with my Kofan colleagues, we quickly come to the conclusion that the miners in the area have fled a while back, taking their digging toys with them once the news of an environmental inspection had spread like wildfire in this gold-boom area at the foothill of the Andes.

Open pools have been left untouched in an area that was teaming with miners a week before the visit. Authorities are seen inspecting one of the site on this drone clip.

Open pools have been left untouched in an area that was teaming with miners a week before the visit. Authorities are seen inspecting one of the site on this drone clip.

Pulling the government by the ears

The reason why this group of more than 20 representatives from various ministries and agencies are roasting under the Amazonian sun is not just because multiple Ecuadorian and International laws have been violated. Nor is it because the water of thousands of people living downstream is under threat from these illegal activities. In fact, the only reason we are all there together looking at the disastrous footprint of this early gold rush is because the Kofan have stood up for their land, documented every move made by the illegal miners, and then pressured every single level of government to act to stop this environmental and human rights nightmare immediately.

Flying the drone has allowed our team and the Kofan people of Sinangoe to detect and monitor the illegal miners in remote areas of the Ecuadorian Amazon. In this picture, the government authorities take a glimpse at the scene from the air through goggles.

With rigorous and systematic monitoring of every move from the miners – mapping, filming and documenting every step – the Kofan people of Sinangoe were able to demonstrate the illegality of the activities and force the Ecuadorian government to act, a first victory in a battle for the safeguard of their land. This comes after years of work for the Kofan who have decided to set in place their own indigenous law and their proper land patrol in order to detect, block and denounce any extractive activities inside their ancestral land. In the struggle to protect the Amazon, Sinangoe demonstrates the importance of indigenous-led land control in order to effectively avoid deforestation, forest degradation and poaching. Now that the authorities have finally seen the mess the Kofan have been denouncing for months, the community is waiting for action from the Prosecutor and the various ministries hoping they lead to canceling once and for all the dozens of mining concessions that have been granted in the area over the past months, and punishment for the mining companies that have operated against the law.

Damage is done, but the worst has been avoided

Over the course of 5 months of illegal mining, the trespassers have built a 2-kilometer road into pristine rainforest- opening Sinangoe’s ancestral land to more invasion. They have deforested over 15 hectares of forest, dug out countless pools, created landslides that have transformed the landscape, installed over 10 makeshift mining camps, modified the course of the Aguarico River, changed its color and turbidity and likely released a large amount of mercury and cyanide into the headwaters of this crucial Amazonian river. This neurotoxic heavy metal may cause health issues for dozens of riverine communities, contaminating the food chain for decades and accumulating into the fish those communities feed on every day.

Digging for gold with heavy machinery in the Amazon takes a heavy toll on the environment and the health of its inhabitants.

Nefarious as these impacts are, the worst has thankfully been avoided. Knowing how bad illegal gold mining in the Amazon can get pushed us to work rigorously, hard and fast to avoid the worst-case scenario. Those ⁓30 000 hectares of mining concessions have been granted for the next 25 years inside and on the borders of ancestral Kofan lands in the headwaters of the Aguarico River, an environmental bomb if it is exploited. More than ever Sinangoe needs support in order to make sure these concessions are canceled, and environmental restoration begins so the land can heal. The community has been discussing possible legal action with Ecuador’s Defensoria del Pueblo- a public institution that defends citizens’ rights- and either with them or without them will be taking legal action to protect their territory, and halt mining in the area.

These are very positive signs which needs to be reinforced. Please stand with Sinangoe to pressure the Ecuadorian government to cancel these mining concessions and respect the community’s right to free, prior and informed consent on any development activities affecting their lands, lives, or culture. By signing the pledge to #StandwithSinangoe, it allows you to add your voice to the movement, provide direct support to Sinangoe and stay informed on future important steps to protect Sinangoe’s land and rights.

List of chronicles in our series on Sinangoe:

Nothing found.

On the frontlines of a new gold rush in the Ecuadorian Amazon

It came out of nowhere. No letters, no meetings, no publicity or any attempt to sell the idea, and from one day to the next, the game had entirely changed. With one approval from the Mining Ministry, what was once a pristine mega-diverse rainforest at the headwaters of one of the main watersheds of the Ecuadorian Amazon had been transformed into a gold mining hotspot.

The headwaters of the Aguarico River, where the Cofanes and Chingual Rivers meet, have been licensed to gold miners. The fate of the area now lies in the hands of the Kofan people who are fighting to protect one of the last intact areas of their ancestral land.

The headwaters of the Aguarico River, where the Cofanes and Chingual Rivers meet, have been licensed to gold miners. The fate of the area now lies in the hands of the Kofan people who are fighting to protect one of the last intact areas of their ancestral land.

Over the past three months, the Ecuadorian government has granted more than 10 new gold mining concessions in the headwaters of the Aguarico River, most within the boundaries of the Cayambe-Coca National Park and home to the ancestral Kofan people of Sinangoe. Despite its direct impact on the community, the rivers, the land and the A’I Kofan way of life, the new mining claims were granted without any prior consultation with Sinangoe, in violation of Ecuadorian law, and most probably without a proper environmental license.

To put it in other words, these operations are totally illegal.

The entire northern and north-eastern border of Sinangoe’s land and Cayambe-Coca National Park have been leased to gold mining interest within the past 3 months. The red areas are mining claims already conceded, the ones in green are still under revision.

A radical change of scale

As described in a previous chronicle, the community of Sinangoe has been monitoring and blocking illegal mining inside their land for years. These invasive activities had significantly dropped following a September 2017 announcement of the community’s Indigenous Law – prohibiting any extractive activities on their land – an encouraging sign for the community that had witnessed an increasing amount of colonos inside its land for years. However, this new wave of gold miners is nothing like what they have witnessed before.

Over two weeks, a patch of pristine rainforest has been transformed into wasteland by gold mining operations. The fast pace has left the community of Sinangoe fearing the worst since these new concessions have been allocated to gold miners for the next 25 years.

Large machinery, huge water pumps, road construction, massive deforestation, noisy operations, gaggles of miners…this birth of a gold rush is a radical change of scale and quite worrisome, seeing how much damage they can do in such a short time. In recent weeks, Sinangoe’s land patrol has observed diggers and large water pumps outside the mining concession limits and inside the river bed, excavating and damaging the Aguarico River. One of the community’s main concerns is that these kinds of gold mining operations in the Amazon often come with the use of highly toxic mercury, a heavy metal that bioaccumulates in fish and can be extremely damaging to the human nervous system.

Sinangoe’s land patrol has witnessed gold miners with heavy machinery digging inside the river bed, and outside their new mining concession, an illegal procedure that hasn’t been met with any sanctions by the authorities so far.

Sinangoe’s land patrol has witnessed gold miners with heavy machinery digging inside the river bed, and outside their new mining concession, an illegal procedure that hasn’t been met with any sanctions by the authorities so far.

Fueled with these new concerns, and with their struggle already attracting media attention at the international level, Sinangoe has increased its monitoring of the area and called upon the provincial and national Ecuadorian authorities to stop these operations. The Environment Ministry, the Mining Ministry, the National Prosecutor, the “Defensoría del Pueblo” and local governments have all been notified and called to action by Sinangoe.

To date, none of them appear to have taken any actions to stop these illegal activities, despite a recent referendum in Ecuador calling for a ban on any mining activities inside protected and sensitive areas. With mining being such a controversial topic in Ecuador, the country’s President Lenin Moreno announced the cancellation of 2,000 mining concessions in February, but we still don’t know if any of the concessions in the Aguarico are part of that list.

With new mining operations using heavy machinery, Sinangoe’s main concern is the high probability that miners use mercury to increase gold extraction, an illegal practice that would damage water and fish stocks and directly threaten the health of thousands of indigenous communities downstream.

Sinangoe joining forces with other mining-impacted communities

On Monday April 16th, more than half of Sinangoe’s population joined a national protest against mining, calling upon the government to cancel all new mining concessions and stop all operations in the headwaters of the Aguarico River.

Members of the Kofan community of Sinangoe took to the streets of Tulcan, Ecuador, along with other communities affected by mining across northern Ecuador, to denounce a recent wave of mining concessions that threaten their health and their territories. Sinangoe and many indigenous communities across Ecuador are standing up against extractive industries that place a higher value on profits than indigenous lives and lands.

To succeed in nullifying these concessions, Sinangoe needs to increase pressure on the Ecuadorian authorities, and your support can make the difference to turn the tables and ensure that Sinangoe’s pristine ancestral rainforest stays intact. Stand with Sinangoe by signing the pledge and by sharing this information with family, friends and colleagues, and stay tuned for further updates and actions to support Sinangoe in their efforts to defend their ancestral homeland..

Watch and share this powerful video about Sinangoe’s community-led efforts to detect and halt illegal activities on their lands.

List of chronicles in our series on Sinangoe:

Nothing found.

What Do We Know About How Oil Spills Affect Human Health? Not Enough.

Planes, trains and automobiles. Plastic, pesticides and polyester. Oil and gas have been the engine of the world economy for 100 years. Despite this, we know little about the health impacts of spills and purposefully discharged oil waste. Why is this? Because not one long-term study has been carried out with residents living near spills or workers who have cleaned up spills. Not one.

Several good, short-term studies have been carried out, however, and what they tell us is troubling. These studies report on health impacts in people exposed to oil and gas from several of the most notorious spills in history: Exxon Valdez, Hebei Spirit, Tasman Spirit, Prestige, and Deepwater Horizon. The portrait they paint is alarming. They are like the iridescent sheen of an oil slick on the surface that entreats us to dig deeper to uncover the enduring effects of contact with oil and gas.

Notorious Oil Spills: When a tanker sinks or a rig close to the United States blows we hear a lot about it in the media, but none of the most notorious spills even come close to the amount of oil and toxic wastes that have been dumped into the Ecuadorian Amazon over the years.

For the past 50 years, the people living in the northern Ecuadorian Amazon have been the victims of countless spills and the irresponsible waste management practices of the companies extracting oil in the region. Between 1972 and 1993, 714 million barrels (or 30 billion gallons) of oil and toxic waste have been purposefully or accidentally released into the environment. While none of the individual spills measure up to the infamous spills named above, over the years they have added up to more than 140 times the 2010 BP Deepwater Horizon spill in the Gulf of Mexico. What’s more, this ‘slow-drip’ means that people are in near-constant contact with oil and waste products. Even less is known about the health impacts of this relentless contact with oil, but the short-term studies carried out on the large-scale spills can give us a clue as to what might be happening among indigenous peoples of the region.

Oil spill near the Kofán community of Avie.

Health impacts of oil spills

Published studies have looked at both self-reported symptoms and biomarkers (laboratory results from samples) in people who came into contact in some way with oil or gas following spills (Aguilera et al. 2010; D’Andrea and Reddy 2014; Laffon et al. 2016; for a recent review see Ramirez et al. 2017). Self-reported symptoms can be grouped into respiratory problems, irritations (eye, skin, etc.), neurological effects (headache, dizziness, etc.) and traumatic symptoms (pain). Symptoms were, in many cases, related to the intensity of the exposure. In other words, the closer the person was to the spill or the more time they spent near the spill, the greater the symptoms. These findings suggest that each time local Ecuadorian Amazonian people are exposed to a spill they suffer these same symptoms. The nonstop contact with oil among indigenous people in the northern Ecuadorian Amazon would presumably have a cumulative effect, making individuals more vulnerable once an accident occurs.

Self-reported skin rashes from contact with an oil spill.

Studies of biomarkers have uncovered irreparable harm to humans exposed to oil and gas from spills. These effects can be grouped into respiratory damage, liver damage, decreased immunity, increased cancer risk, reproductive damage and higher levels of some toxics (hydrocarbons and heavy metals).

The only study looking at Amazonian indigenous people’s health markers following a spill was carried out in the Peruvian Amazon four months after a localized spill (Webb et al. 2016). The study showed that men who had worked cleaning up the spill had twice as much mercury in their urine as did men who had not been involved in the effort to restore the lagoon in which the oil had stagnated. Mercury damages the brain and the liver. Each time a pipeline ruptures or a waste pit overflows, we could expect that the people in the vicinity are flooded with mercury, through their water, the fish they eat, and the air they breathe. Several other studies conducted in the Ecuadorian Amazon have linked proximity to oil operations with illness (such as cancer, skin irritations, etc.) (San Sebastian et al. 2001; 2004; Hurtig et al. 2004; Paz-y-Miño et al. 2008). While the studies were not linked to a specific spill, they were carried out in areas having borne numerous accidents. Two studies, both financially supported by Chevron, unsurprisingly, found no link between cancer and oil extraction (Kelsh et al. 2009; Moolgavkar et al. 2014).

Where do we go next?

The longest-term study ever carried out followed fishers six years after the Prestige oil spill off the coast of Spain and evaluated respiratory health effects. A clinical study looking at the effect of water from the Gulf of Mexico following the Deepwater Horizon oil spill found that human lung cells grown in the water, which contained both the spilled oil and oil dispersants, showed signs of damage, pointing to some of the ways in which oil and dispersants wreak havoc on the human body. From other clinical studies (on mice and cells) we know that one of the main health effects of hydrocarbons, the principal component of oil, is cancer. In order to capture cancer rates, studies need to run for an extended period of time. A longitudinal (long-term) study on the impacts of oil spills is needed.

What can you do?

Reducing the demand for oil is the best way that individual citizens can reduce the number of spills. In order to reduce your consumption, take public transportation, eat local, eat lower on the food chain (vegetarian), and consume less. You can also demand that your institutions (bank, school, municipality) divest from oil companies. Amazon Frontlines is working with the indigenous organization Ceibo Alliance to help indigenous people know what risks they face. Knowing the risks is the first step in being able to take action to defend indigenous rights to health and demand greater environmental protections in the Amazon. See the work of our Environmental Monitoring and contribute to this work here.

Reference list

- Aguilera F, Méndez J, Pásaro E, Laffon B (2010) Review on the effects of exposure to spilled oils on human health Journal of Applied Toxicology 30:291-301 doi:10.1002/jat.1521

- D’Andrea MA, Reddy GK (2014) Crude oil spill exposure and human health risks Journal of occupational and environmental medicine 56:1029-1041

- Hurtig A-K, San Sebastián M (2004) Incidence of Childhood Leukemia and Oil Exploitation in the Amazon Basin of Ecuador Int J Occup Environ Health 10:245-250

- Kelsh M, Morimoto L, Lau E (2009) Cancer mortality and oil production in the Amazon Region of Ecuador, 1990–2005 Int Arch Occup Environ Health 82:381-395

- Laffon B, Pásaro E, Valdiglesias V (2016) Effects of exposure to oil spills on human health: updated review Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part B 19:105-128

- Moolgavkar SH, Chang ET, Watson H, Lau EC (2014) Cancer mortality and quantitative oil production in the Amazon region of Ecuador, 1990–2010 Cancer Causes Control 25:59-72 doi:10.1007/s10552-013-0308-8

- Paz-y-Miño C, López-Cortés A, Arévalo M, Sánchez ME (2008) Monitoring of DNA Damage in Individuals Exposed to Petroleum Hydrocarbons in Ecuador Ann N Y Acad Sci 1140:121-128 doi:10.1196/annals.1454.013

- Ramirez MI, Arevalo AP, Sotomayor S, Bailon-Moscoso N (2017) Contamination by oil crude extraction – Refinement and their effects on human health Environmental Pollution 231:415-425 doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2017.08.017

- San Sebastian M, Armstrong B, Cordoba JA, Stephens C (2001) Exposures and cancer incidence near oil fields in the Amazon basin of Ecuador Occupational & Environmental Medecine 58:517-522

- San Sebastian M, Hurtig AK (2004) Oil exploitation in the Amazon basin of Ecuador: a public health emergency Rev Panam Salud Publica 15:205-211

- Webb J, Coomes OT, Mergler D, Ross N (2016) Mercury Concentrations in Urine of Amerindian Populations Near Oil Fields in the Peruvian and Ecuadorian Amazon Environmental Research 151:344-350

List of chronicles in our Health on the Frontlines series:

Nothing found.

Be a Champion for the Amazon!

Start a fundraising campaign to drive resources to Indigenous Earth Defenders on the frontlines

Confronting illegal mining in ancestral Kofan land, Ecuadorian Amazon

The waves of the Upper Aguarico River are crashing on both sides of our boat, filling it with cold water rushing straight from the Andes, which stand tall in front of us. The puntero barks and points directions to the motorista in order to avoid smashing into one of the many boulders in our way, and my heart pumps fast with the adrenaline rush. My eyes feast on the wild landscape while my mind races: Where are they? Will we meet the same ones? How should we react if they become aggressive?

The land patrol of Sinangoe travels up the Aguarico River towards an area known to the Kofan people as a “hotspot” for illegal gold mining, hoping to stop what seems to have become an “Amazonian Gold Rush” on their ancestral land.

The land patrol of Sinangoe travels up the Aguarico River towards an area known to the Kofan people as a “hotspot” for illegal gold mining, hoping to stop what seems to have become an “Amazonian Gold Rush” on their ancestral land.

It is the fifth time in a little more than a month that our team has traveled to this far corner of the Amazon, in the mega-diverse foothills of the Ecuadorian Andes. This area has been the traditional Kofan territory of Sinangoe since time immemorial, more recently designated by the Ecuadorian government as the Cayambe-Coca National Park. If you close your eyes and think of the Amazon, Sinangoe represents everything you can imagine: rich indigenous culture, splendid wildlife, ancient lianas and giant trees, beautiful landscapes… And a lot of rain, falling in sporadic downpours and fueling hundreds of streams, waterfalls and rivers.

However, behind the luxuriant curtain of the jungle, hides a disconcerting reality: While the patch of green that represents the National Park might look nice on a map, illegal miners, fishermen and poachers are currently roaming inside Sinangoe’s land without consent from the community or any meaningful control from the government — and the Kofan people have had enough. Our team, composed of Sinangoe’s leaders and land defenders, is on the lookout.

Monitoring the elusive “homo illegalis”

We have reached the section of the river where boats can go no further, and are now walking on a trail that seems to be used every day by dozens of people. Footprints in the mud, an oddly broken branch, new trails leading deeper in the jungle, an empty shotgun cartridge, remnants of a makeshift camp, garbage left in a clearing… The signs of the “Amazon gold rush” are obvious, even for a foreigner like me. The Kofan people have been walking these woods for millennia, but rarely have they seen so many indications of the ongoing occupation of their land by the “cucamas”- the “outsiders.”

Facing increased pressure on their land, the Kofan people of Sinangoe have decided to work with the Ceibo Alliance and Amazon Frontlines in a monitoring project aimed at detecting, documenting and denouncing illegal activities in their traditional territory. Through the use of community land patrols, camera trap photos and videos, drone footage, satellite imagery and territorial mapping, the community is channeling reliable, evidence-based, real-time information about invaders to help decision-making processes in order to defend their ancestral land.

The team of Kofan land defenders from Sinangoe has been using camera traps, drones, GPS and video cameras to detect illegal activities on their ancestral land.

The team of Kofan land defenders from Sinangoe has been using camera traps, drones, GPS and video cameras to detect illegal activities on their ancestral land.

After walking for fifteen minutes, we reach the first camera trap, well hidden in the trees. Trepidation takes over our team. Since we installed the camera two weeks ago, it has been very active: The small lcd screen indicates that the memory card is filled with 168 pictures and videos. Triggered by movement and equipped with heat sensors, these camera traps are usually used to detect wildlife, but we have adapted our monitoring to detect another kind of species: homo illegalis- the illegal colonist invader. And it seems our first camera of the day will provide very valuable clues on the habits of this elusive species.

Settled on a big rock close to a stream, the team focuses on the laptop we downloaded the images onto, hoping the approaching rain clouds above don’t bring a quick end to our improvised forest desk. Flipping through the gallery, the faces of my Kofan colleagues change from excitement to awe to indignation. The pictures and videos show dozens of intruders on this very spot, walking in pairs or in groups of up to eight people, some with gasoline tanks, others with shotguns, shovels or pickaxes, all heading upriver at dawn and coming back down at dusk, sometimes two or three days after they first walked by.

Over the course of less than four months of monitoring, from February to May 2017, the Kofan people of Sinangoe have detected more than 70 people, often working in groups, participating in illegal activities on their ancestral land.

We’re snacking on crackers as we look at the faces of the illegal miners and poachers on the screen while the elders of the group give us information as to who these people are. Some of them are well known colono neighbors of Sinangoe, but many faces are unknown to the team, a sign that things might be getting out of control. Moreover, some of the illegal miners that triggered our camera traps have been previously warned by our team many times yet continue to show up. It seems like the message still isn’t getting across.

When words don’t mean anything anymore

We are back on the trail, going upstream along the Upper Aguarico River, when someone in our group stops, pointing with his finger to his ear. We all stop and listen carefully. At first, I can hear nothing else other than the constant variety of jungle sounds- crickets, birds, cicadas and frogs. But after a while I catch it, behind the general din, a humming sound that can only be coming from one thing: a motor. We decide to go to the river bank, towards the sound.

One of our team members sees something move, about 500 meters from where we are standing. Instead of going right away to confront whomever it might be, we decide to fly the drone and get a peek of what is going on upstream. After a two-minute flight, the drone shows us the source of the noise. On a small stream leading to the main River, deep into Sinangoe’s ancestral land, three men are illicitly digging the pristine shore with a dredger in the hope of finding gold. Having visited this site two weeks earlier, we can see that they have transformed the landscape considerably.

Caught by our drone hiding in the trees, a group of illegal miners are dredging a small catchment of the Upper Aguarico River, deep into ancestral Kofan land and inside the Cayambe-Coca National Park.

Caught by our drone hiding in the trees, a group of illegal miners are dredging a small catchment of the Upper Aguarico River, deep into ancestral Kofan land and inside the Cayambe-Coca National Park.

Even though we are filming from a considerable height, it seems the miners have heard the drone and hurry to hide in the trees. We bring the drone back to us, and decide to go straight to the men to have a talk. After a five-minute walk, we arrive at the dredger, which had been shut down, and realize the illegal miners are actually the same ones who told us a week-and-a-half ago that they never used machinery and would not come back to the area.

There is obvious discomfort in the air.

Sinangoe’s land patrol has warned dozens of illegal goldminers in the past months, asking them to respect their ancestral land and not exploit resources without their consent. In this exchange, a goldminer responds to the question “why are you coming to the very place the community says not to come, where the government says not to come and where you have no permit to do such mining?” The answer: “Let’s be honest, we are taking advantage of the situation… but give us one last chance and we will leave”.

Sinangoe’s land patrol has warned dozens of illegal goldminers in the past months, asking them to respect their ancestral land and not exploit resources without their consent. In this exchange, a goldminer responds to the question “why are you coming to the very place the community says not to come, where the government says not to come and where you have no permit to do such mining?” The answer: “Let’s be honest, we are taking advantage of the situation… but give us one last chance and we will leave”.

From what we see, the men have been at work for many days. We can make out their makeshift camp in the trees, not far away. Once again, we all sit to have a talk — the Kofan always polite and calm; the miners, apologetic and defensive. Why are they coming back to the very place where the Kofan asked them not to come? Their answer is quite straightforward: “Let’s be honest, we are taking advantage of the situation… But give us one last chance and we will leave”.

The problem is, this conversation sounds like a broken record, and everyone in the group knows it.

Indigenous legal strides against colonists’ illegal mining

Fed up with these kinds of encounters and of so many other abuses over the years, and the total lack of support from Ecuadorian authorities, the community of Sinangoe decided in May 2017 to adopt its own indigenous law and to put in place a formal land patrol to monitor and stop illegal activities on their land. Made public in September 2017, this new legal tool, supported by Ecuadorian Constitution and international treaties, prohibits any mining, poaching, fishing or logging by non-Kofan people on their land and sets strict rules on how invaders should be treated.

The entire community of Sinangoe have unanimously adopted its indigenous law in May 2017 in order to stop illegal activities inside their ancestral land.

As a direct response to these legal strides and the publicity it attracted, the local, provincial and national authorities have been forced to react, starting investigations and going with Sinangoe’s land patrol on the field to witness the illegal activities with their own eyes. Unfortunately, to this date, not one authority – either from the Ministry of the Environment, the “Defensoria del Pueblo” or the local or National Police – have acted against any of the invaders or set any sanctions.

However, illegal miners have since had to think twice before crossing into Sinangoe’s land, and the community has observed a drastic drop in invasive activities since they publicized their law in September 2017. Meanwhile, the land patrol keeps on walking their woods, constantly on the lookout for any infringement on their ancestral land.

In the early months of 2018, Sinangoe’s land patrol have found what they have feared for years: it seems like the reputation of the area as a good “gold spot” has reached bigger players’ ears. From one day to the next, big machinery has appeared on the very edge of their land, new mining concessions have been granted without any prior consultation. Definitely, this fight is far from over…

For the Kofan of Sinangoe, standing up in defense of their territory requires courage and it requires solidarity. Stand with Sinangoe by signing and sharing our pledge.

List of chronicles in our series on Sinangoe:

Nothing found.